Let Me Dream Again

Plot

Let Me Dream Again presents a pioneering narrative sequence that begins with a man passionately kissing a beautiful young woman in a romantic setting. The image then deliberately blurs and dissolves through a sophisticated focus-pulling technique, transitioning seamlessly to reveal the same man waking up in bed beside his plain, nagging wife. The wife scolds him for his dream, creating a comedic contrast between fantasy and reality. The film concludes with the man's disappointment as he realizes his romantic encounter was merely a dream, highlighting the universal theme of escapism from marital dissatisfaction. This brief but impactful narrative demonstrates early cinema's ability to convey complex emotional states through visual storytelling alone.

Director

Cast

About the Production

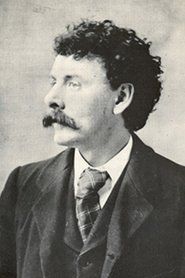

Filmed in George Albert Smith's studio in St. Ann's Well Gardens, Brighton. The film was shot on 35mm film using a stationary camera, with the innovative focus pull achieved through manual adjustment of the camera lens during filming. The production utilized natural lighting and simple sets typical of the period. The entire film was likely completed in a single day of shooting, which was standard for one-minute films of this era.

Historical Background

Let Me Dream Again was created during the infancy of cinema, when films were primarily short novelty attractions shown in music halls and fairgrounds. The year 1900 marked a transitional period in British cinema, moving away from simple actualities and trick films toward more complex narratives. George Albert Smith was part of the Brighton School of filmmakers, who were experimenting with cinematic language and techniques that would become fundamental to the medium. This period saw the development of continuity editing, close-ups, and special effects techniques. The film emerged at a time when audiences were still discovering the possibilities of cinema, and filmmakers were establishing the vocabulary of this new art form. The Victorian era's strict social mores made the film's theme of marital dissatisfaction and romantic fantasy somewhat daring for its time.

Why This Film Matters

Let Me Dream Again holds immense cultural significance as a technical and narrative milestone in early cinema. The film's pioneering use of focus pulling established a cinematic technique that would become fundamental to visual storytelling, allowing filmmakers to guide audience attention and create emotional transitions. It represents one of the earliest examples of psychological cinema, exploring the inner world of characters rather than just external actions. The dream sequence format it helped establish would become a recurring trope in cinema, used by filmmakers from Hitchcock to Lynch. The film also demonstrates early cinema's ability to comment on social realities, in this case the constraints of marriage and the human desire for escapism. Its influence can be seen in countless subsequent films that use similar transitions between fantasy and reality. The film is now recognized by film historians as a crucial step in the development of cinematic language and visual storytelling techniques.

Making Of

George Albert Smith, a former stage hypnotist and magic lantern showman, brought his understanding of visual illusion to this pioneering film. The production took place in Smith's Brighton studio, where he had converted a glasshouse into a film studio to utilize natural lighting. The focus pulling technique required Smith to manually adjust the camera lens while the camera was running, a difficult feat with the primitive equipment of 1900. Laura Bayley, Smith's wife, played the role of the nagging wife, while Tom Green portrayed the dreaming husband. The film was likely shot in one take with careful rehearsal to achieve the timing of the focus transition. Smith's background in magic shows influenced his approach to film as a medium for visual trickery and illusion, which is evident in this film's technical innovation.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Let Me Dream Again represents a significant technical achievement for its time. The film was shot using a stationary camera, which was standard practice in 1900, but incorporated the innovative technique of focus pulling during a single take. This required the cinematographer to manually adjust the lens focus from sharp to blur and back to sharp again, creating a smooth transition between the dream and reality sequences. The film utilized natural lighting, likely shot in Smith's glasshouse studio. The composition was simple but effective, with the romantic scene featuring the young woman in a flattering pose, while the waking scene showed the wife in a more mundane setting. The cinematography demonstrates early understanding of how visual techniques could convey psychological states and narrative transitions without the need for intertitles or dialogue.

Innovations

Let Me Dream Again's primary technical achievement is its pioneering use of focus pulling (rack focus), making it one of the first films to use this technique as a narrative device. The blur and refocus effect was achieved manually during filming, requiring precise timing and coordination. The film also demonstrates early use of the dissolve technique, transitioning smoothly between the dream and reality sequences. The production utilized Smith's development of the close-up technique, though in this case it was more about selective focus than camera positioning. The film represents an early example of psychological storytelling through visual means, showing how technical innovations could serve narrative purposes. These techniques, while simple by modern standards, were groundbreaking for 1900 and would become fundamental to cinematic language in the decades that followed.

Music

As a silent film from 1900, Let Me Dream Again had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or chosen from standard repertoire, with romantic music during the dream sequence and more comedic or mundane music for the reality sequence. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects, such as a kiss sound effect or a scolding voice for the wife, though this was not standard practice. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores that attempt to match the film's emotional arc, typically shifting from romantic to comedic themes to match the visual narrative.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic focus pull sequence where the romantic kiss with the beautiful woman blurs and transitions to the man waking up with his nagging wife - this technical innovation represents one of cinema's first uses of selective focus as a narrative device, creating a seamless psychological transition between fantasy and reality that would influence filmmakers for decades to come.

Did You Know?

- Considered one of the first films to use the technique of focus pulling (rack focus), transitioning from a sharp image to blur and back to sharp again

- The film represents an early example of psychological cinema, exploring the inner world of dreams versus reality

- Director George Albert Smith was a pioneer of British cinema who developed many early film techniques

- The film was part of Smith's series of 'dream' films that explored psychological themes

- It predates D.W. Griffith's similar techniques by over a decade

- The film was distributed by the Warwick Trading Company, one of the major early film distributors

- The blur effect was achieved by manually adjusting the camera's focus during the shot, requiring precise timing

- The film is only 62 feet long, running approximately one minute at 16 frames per second

- It represents an early use of the 'dream sequence' trope that would become common in later cinema

- The film's title itself suggests the theme of escapism and the desire to remain in fantasy rather than face reality

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Let Me Dream Again is difficult to document as film criticism was not yet established as a profession in 1900. However, the film was likely well-received by audiences of its time as a clever novelty. Modern critics and film historians have recognized the film as a significant technical achievement. The British Film Institute and film scholars have praised Smith's innovation in using focus as a narrative device. The film is now studied in film history courses as an example of early cinematic technique and the development of visual language. Critics have noted how the film demonstrates that sophisticated psychological storytelling was possible even in the earliest days of cinema, challenging the notion that early films were merely primitive entertainment.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1900 would have been marked by fascination with the film's technical innovation, as the focus pulling effect would have appeared magical to viewers unfamiliar with such techniques. The film's relatable theme of escaping an unhappy reality through dreams would have resonated with Victorian audiences. The comedic contrast between the romantic fantasy and mundane reality would have provided entertainment value. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals appreciate it primarily for its historical significance and technical innovation. The film is now primarily viewed by film enthusiasts, students, and scholars rather than general audiences, serving as an important artifact in understanding the development of cinema as an art form.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Magic lantern shows

- Stage hypnotism

- Early trick films

- Victorian theatrical traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906)

- Dream Street (1921)

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Various films using dream sequences

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the BFI National Archive and has been digitally restored. Prints are also held by other film archives including the Library of Congress. The restoration has allowed modern audiences to appreciate the film's technical innovations. The film survives in good condition considering its age, though some deterioration is visible in existing prints.