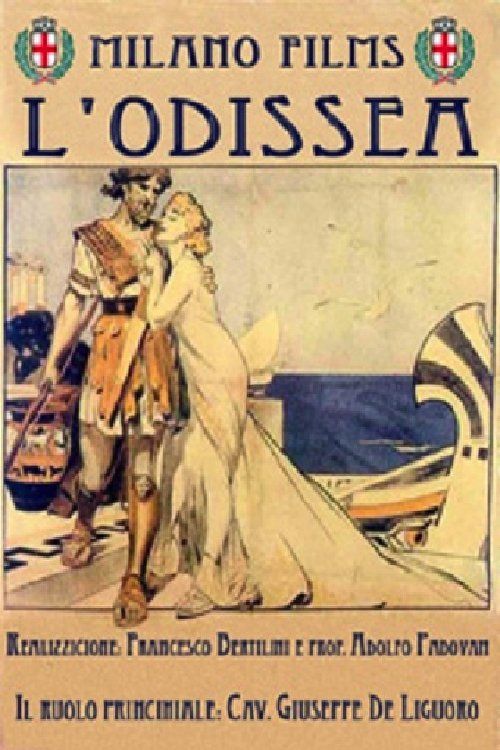

L'Odissea

Plot

This ambitious 1911 Italian silent epic brings Homer's ancient Greek masterpiece to life, following the decade-long journey of Odysseus as he attempts to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War. The film chronicles his encounters with mythical creatures including the Cyclops Polyphemus, the enchantress Circe, the Sirens, and the sea monster Scylla, while his faithful wife Penelope fends off suitors who believe Odysseus dead. After facing divine wrath from Poseidon and temptations from various goddesses, Odysseus finally returns disguised as a beggar to reclaim his kingdom and reunite with his family. The adaptation captures the epic scope of Homer's tale through elaborate sets, costumes, and special effects that were groundbreaking for their time. The film concludes with Odysseus reclaiming his throne and reuniting with his son Telemachus and wife Penelope, restoring order to his kingdom.

About the Production

This was one of the most ambitious and expensive Italian productions of its time, requiring massive sets including detailed recreations of ancient Greek temples, palaces, and mythological locations. The production employed hundreds of extras and utilized groundbreaking special effects techniques including miniatures, matte paintings, and early forms of stop-motion animation to create the mythological creatures. The Cyclops sequence was particularly innovative, using forced perspective and oversized props to create the illusion of a giant. The film was shot over several months and required the construction of elaborate water tanks for the sea sequences. The production team consulted classical scholars to ensure authenticity in the costumes and set designs, though they took artistic liberties for dramatic effect.

Historical Background

L'Odissea was produced during what many film historians consider the golden age of Italian cinema (1909-1914), a period when Italian films dominated the international market. This era saw Italian filmmakers pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling with increasingly ambitious epics and historical dramas. The film emerged at a time when cinema was transitioning from short novelty films to feature-length narratives that could compete with theater and literature. Italy's strong classical heritage made Greek mythology a natural subject for filmmakers, and the country's growing film industry had the resources to mount such productions. The film's creation coincided with significant technological advancements in cinematography and special effects, allowing for more sophisticated visual storytelling. The early 1910s also saw growing international interest in educational and cultural films, making literary adaptations particularly marketable.

Why This Film Matters

L'Odissea represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, demonstrating that film could successfully adapt complex literary works and handle epic narratives. The film helped establish the epic as a viable cinematic genre and proved that audiences would sit through longer, more sophisticated stories. Its success inspired a wave of literary adaptations across Europe and America, influencing filmmakers like D.W. Griffith, who would later create his own epics such as 'Intolerance' (1916). The film also demonstrated cinema's potential as an educational medium, bringing classical literature to mass audiences who might never have read Homer's original work. Its technical innovations in special effects and set design pushed the boundaries of what was possible in early cinema, influencing production techniques for decades. The film's international success helped establish Italian cinema as a major cultural export and contributed to the globalization of film as an art form.

Making Of

The making of 'L'Odissea' was a monumental undertaking that pushed the boundaries of early cinema. Director Francesco Bertolini, working with co-directors Adolfo Padovan and Giuseppe de Liguoro, faced the challenge of adapting one of literature's most epic works to the limitations of 1911 filmmaking technology. The production team at Milano Film invested unprecedented resources into the project, building massive sets that included full-scale replicas of ancient Greek architecture. The most challenging sequence was the Cyclops encounter, which required innovative solutions including building a giant mechanical eye and using perspective tricks. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with de Liguoro studying classical Greek sculpture to perfect his portrayal of Odysseus. The film's success led to a wave of Italian literary adaptations and established a template for epic filmmaking that would influence directors like D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille.

Visual Style

The cinematography of L'Odissea was groundbreaking for its time, utilizing techniques that were innovative in 1911. The film employed extensive use of location shooting combined with elaborate studio sets, creating a visual variety that impressed contemporary audiences. The cinematographers experimented with lighting to create dramatic effects, particularly in the underworld sequences where they used colored filters and gels to create an otherworldly atmosphere. The film made innovative use of camera movement, including tracking shots during battle sequences and sweeping pans to establish the scale of the sets. Special effects photography was particularly sophisticated, using multiple exposures, matte paintings, and miniature work to create the mythological elements. The Cyclops sequence featured pioneering use of forced perspective and oversized props to create the illusion of giants. The film also experimented with hand-coloring certain sequences, particularly those involving gods and supernatural elements, to enhance their visual impact.

Innovations

L'Odissea showcased several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1911. The film pioneered advanced special effects techniques including sophisticated matte painting, miniatures, and early forms of stop-motion animation for the mythological creatures. The production developed innovative camera techniques for creating the illusion of giant size in the Cyclops sequences, using forced perspective and oversized props. The film featured some of the most elaborate set constructions of its era, including massive temple replicas and detailed palace interiors that could be filmed from multiple angles. The underwater sequences were particularly innovative, filmed using custom-built water tanks and early waterproof camera housing. The film also experimented with color tinting and hand-coloring techniques to enhance the visual impact of supernatural elements. The production's use of multiple cameras for complex scenes allowed for more dynamic editing and pacing than was typical of the period.

Music

As a silent film, L'Odissea was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and location. The production company provided suggested musical cues for theater organists or small orchestras, recommending classical pieces that matched the epic nature of the story. In major cities, the film was often accompanied by full orchestras performing specially composed scores that incorporated elements of ancient Greek musical modes. Some theaters used Wagner's operatic works as accompaniment, drawing parallels between Norse and Greek mythology. The film's Italian premiere featured a newly composed score by Giovanni Orefice, who incorporated themes from Italian opera and classical music. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly commissioned scores that attempt to recreate the spirit of the original accompaniments while using contemporary musical sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'Ten years have passed since the fall of Troy, and still Odysseus wanders the seas, cursed by the gods.'

(Intertitle) 'I am Odysseus, son of Laertes, known to all for my cunning.'

(Intertitle) 'No man can escape his fate, but the wise man can shape it to his will.'

(Intertitle) 'Home is not merely a place, but the people who wait for your return.'

(Intertitle) 'The gods test us not to break us, but to reveal our true nature.'

Memorable Scenes

- The Cyclops sequence where Odysseus and his men are trapped in the cave and blind the giant Polyphemus, featuring groundbreaking special effects for the time. The scene uses forced perspective, oversized props, and innovative camera work to create the illusion of a massive one-eyed monster, culminating in the dramatic escape where the men hide under sheep to slip past the blinded Cyclops.

- The Sirens sequence where Odysseus has himself tied to the mast while his crew plugs their ears with wax, creating a visually striking scene that demonstrates the hero's wisdom and self-control.

- The return to Ithaca where Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, tests the loyalty of his servants and the virtue of his wife Penelope, leading to the dramatic reveal and slaughter of the suitors.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest feature-length film adaptations of classical literature, predating many famous literary adaptations by decades.

- The film was originally released in multiple parts across several weeks, as was common for long films in the early 1910s.

- Giuseppe de Liguoro, who played Odysseus, was one of Italy's first film stars and had a background in theater before transitioning to cinema.

- The Cyclops Polyphemus was created using a combination of an actor on stilts, oversized props, and clever camera angles to create the illusion of enormous size.

- The film's success helped establish Italy as a major force in international cinema during the silent era.

- Some scenes were hand-colored frame by frame, a labor-intensive process that added to the film's visual spectacle.

- The production used real animals in several scenes, including live horses for the chariot sequences.

- The film was exported internationally and found particular success in the United States, where it was marketed as an educational film about classical literature.

- The original Italian intertitles were written in verse to maintain the poetic quality of Homer's original work.

- The film's special effects were so advanced for their time that other studios studied their techniques for years afterward.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised L'Odissea as a masterpiece of early cinema, with particular acclaim for its ambitious scope and technical achievements. Italian newspapers hailed it as a triumph of national cinema and evidence of Italy's cultural superiority in filmmaking. International critics, especially in France and the United States, marveled at the film's elaborate sets and special effects, with many noting how successfully it brought ancient Greece to life on screen. Modern film historians consider the film a landmark achievement in early cinema, though some note that its pacing and acting style reflect the theatrical conventions of its era. The film is frequently cited in scholarly works about early epics and literary adaptations, with particular attention paid to its innovative special effects techniques. Recent restorations have allowed contemporary critics to appreciate the film's artistry anew, with many surprised by the sophistication of its visual storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

L'Odissea was a tremendous commercial success upon its release, drawing large crowds across Italy and throughout Europe. Audiences were particularly captivated by the spectacular special effects and elaborate production design, which were unlike anything they had seen before. The film's educational appeal made it popular with schools and cultural institutions, leading to special screenings for students and intellectual societies. In the United States, the film found success both as entertainment and as an educational tool, with many theaters promoting it as a way to experience classical literature. Contemporary audience accounts suggest that viewers were especially impressed by the Cyclops sequence and the various mythological creatures, which created a sense of wonder and spectacle. The film's success led to increased demand for literary adaptations and established a market for feature-length films that could sustain audience attention for over an hour.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Jury Prize, International Film Exhibition, Milan 1911

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Homer's The Odyssey

- Ancient Greek mythology

- Italian opera traditions

- Classical Greek theater

- 19th-century academic painting

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi's architectural engravings

This Film Influenced

- The Odyssey (1997)

- O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

- Ulysses (1954)

- The Odyssey (mini-series, 1997)

- Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

- Clash of the Titans (1981)

- Intolerance (1916)

- Cabiria (1914)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

L'Odissea is considered partially preserved, with approximately 45-50 minutes of the original 68-minute film surviving in various archives around the world. The surviving footage has been restored by several institutions including the Cineteca Italiana in Milan and the British Film Institute. The most complete version was assembled from prints found in Italian, French, and American archives, though some sequences remain missing or exist only in poor quality. The film has undergone digital restoration efforts in recent years, with color tinting reconstructed based on contemporary descriptions. Some scenes, particularly those involving the Cyclops and certain mythological encounters, survive only in fragmentary form. The preservation status represents both the challenges of maintaining early cinema and the importance of international archival cooperation in saving film heritage.