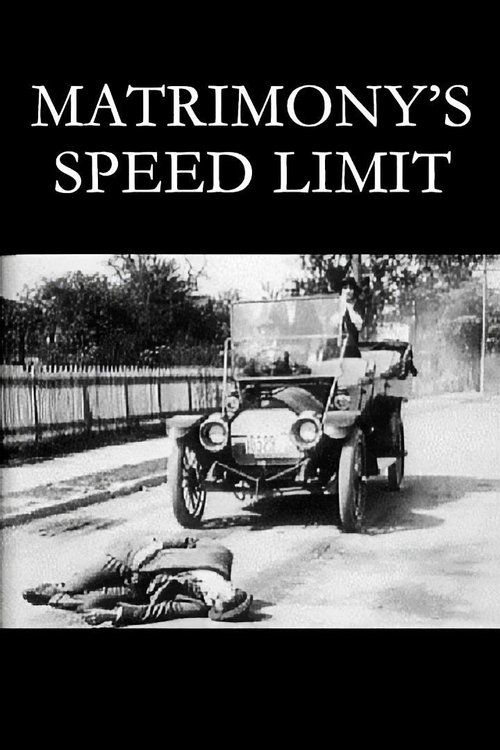

Matrimony's Speed Limit

Plot

In this frantic comedy, a young man discovers through a telegram that he must be married by noon or lose his substantial inheritance. With only ten minutes remaining until the deadline, he desperately searches the city for his fiancée, encountering numerous obstacles and comic situations along the way. The race against time creates a series of increasingly absurd scenarios as he tries to track down his beloved before the clock strikes twelve. The film culminates in a mad dash to the altar, questioning whether love or money is the true motivator for marriage in this early 20th-century society.

Director

About the Production

Filmed at Solax Studios in Fort Lee, which was then the center of American film production before Hollywood's rise. The film showcases Alice Guy-Blaché's signature use of location shooting and dynamic camera movement, which was innovative for the period. The clock motif was prominently featured throughout to maintain tension, requiring careful timing in the editing process.

Historical Background

1913 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring just as feature films were beginning to emerge and the film industry was consolidating its power. The United States was experiencing rapid industrialization and urbanization, with changing social attitudes toward marriage, gender roles, and wealth. Women's suffrage was gaining momentum, making Alice Guy-Blaché's position as a female studio owner particularly remarkable. The film industry was transitioning from its experimental phase to a more commercialized enterprise, with Fort Lee, New Jersey, serving as the unlikely capital before the migration to Hollywood. This period saw the development of film language and techniques that would define cinema for decades to come.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early American comedy and demonstrates Alice Guy-Blaché's significant contributions to cinematic language. As one of the few surviving works by a pioneering female director from this era, it provides crucial evidence of women's foundational role in film history. The film's commentary on marriage and inheritance reflects Progressive Era debates about traditional institutions. Its preservation helps counter the historical erasure of female filmmakers and showcases the sophisticated storytelling techniques being developed in American cinema before the Hollywood studio system's dominance. The film also documents the brief but important period when New Jersey was the center of American film production.

Making Of

Alice Guy-Blaché directed this film during her most productive period at Solax Studios, where she had complete creative control. The film was shot on location in Fort Lee, taking advantage of the town's urban settings to create the frantic chase sequences. Guy-Blaché was known for her efficient directing style and often completed films like this in just a few days. The casting of Fraunie Fraunholz, a regular in her productions, ensured the comic timing would be precise. The film's tight structure demonstrates Guy-Blaché's mastery of narrative pacing, a skill she developed over more than a decade in filmmaking since starting at Gaumont in France.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Solax Productions, utilized natural lighting and location shooting to create a sense of realism. The camera work included dynamic movement for chase sequences, which was innovative for the period. Guy-Blaché employed close-ups and medium shots strategically to emphasize character reactions and build comedic tension. The visual storytelling relied heavily on composition and movement rather than intertitles, demonstrating the emerging visual language of cinema. Clock faces and timepieces were prominently featured to maintain the countdown tension.

Innovations

The film demonstrates Alice Guy-Blaché's innovative use of cross-cutting to build tension during the chase sequences. The effective use of location shooting rather than studio sets was relatively advanced for 1913. The film's editing techniques, particularly the parallel action sequences showing the passage of time, were sophisticated for the period. Guy-Blaché's efficient production methods at Solax Studios, allowing for rapid completion of quality shorts, represented an important development in film production organization.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. Theaters typically provided piano or organ accompaniment, with music chosen to match the film's frantic pace and comedic tone. Specific musical scores were not usually composed for individual shorts of this era, leaving musical selection to the theater's accompanist. Modern screenings often feature newly composed scores that reflect contemporary understanding of silent film accompaniment while respecting the film's period.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue exists as this is a silent film; intertitles would have contained minimal text to advance the plot

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where the protagonist receives the telegram revealing the marriage deadline

- The frantic search through city streets encountering various obstacles

- The climactic race to the altar with minutes ticking away

- The final resolution questioning the nature of his marriage motivation

Did You Know?

- Alice Guy-Blaché was one of the first female film directors in history and possibly the first to own and operate her own film studio

- The Solax Company, founded by Guy-Blaché, was one of the pre-Hollywood film industry's most successful studios

- This film is part of Guy-Blaché's series of comedies exploring gender roles and marriage conventions

- The film was made during the peak of Fort Lee, New Jersey's reign as America's film capital

- Fraunie Fraunholz was a popular comic actor of the era who frequently worked with Guy-Blaché

- The clock countdown technique used in this film would later become a staple of thriller cinema

- Only a fraction of Guy-Blaché's estimated 1,000+ films survive today

- The film's theme of marriage for money versus love was a progressive topic for 1913

- Guy-Blaché often used comedy to subtly critique social norms of her time

- The Solax studio was the largest film studio in America when this film was made

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from trade publications like The Moving Picture World praised the film's comedic timing and clever premise, though detailed critical analysis was limited in 1913. Modern film historians and scholars recognize it as an exemplary work of early American comedy and a testament to Alice Guy-Blaché's directorial skill. The film is frequently cited in academic discussions about early cinema and women's contributions to film history. Critics today appreciate how Guy-Blaché used the comedy genre to explore serious social themes while maintaining entertainment value.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of 1913, who enjoyed the fast-paced comedy and relatable premise. The race-against-time format proved particularly engaging for early cinema audiences. Modern audiences viewing the film through archival screenings and film festivals often express surprise at its sophistication and contemporary relevance. The film serves as an accessible introduction to Alice Guy-Blaché's work for contemporary viewers, helping to restore recognition of her place in film history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French comedy traditions from Guy-Blaché's Gaumont period

- American slapstick comedy emerging at the time

- Chase sequences popularized by early comedies

- Social comedy films examining marriage conventions

This Film Influenced

- Later race-against-time comedies

- Deadline-based narrative films

- Marriage comedies of the 1920s and 1930s

- Works by other female directors inspired by Guy-Blaché's success

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and is considered one of the fortunate few of Alice Guy-Blaché's works to have been preserved. Copies exist in film archives including the Library of Congress and the Women Film Pioneers Project collections. The preservation status allows for continued study and exhibition of this important early work.