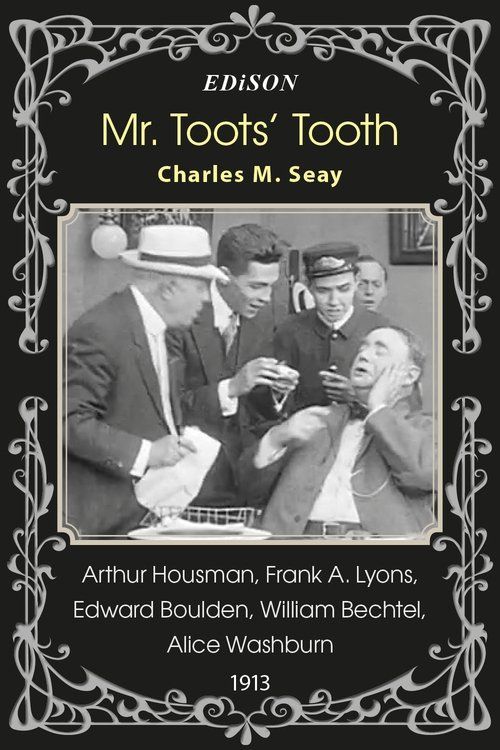

Mr. Toots' Tooth

Plot

In this silent comedy short, Mr. Toots suffers from an excruciating toothache that drives him to try various desperate remedies for relief. He attempts multiple cures and treatments, each more ridiculous than the last, as his pain intensifies throughout the film. Finally resorting to a classic folk remedy, Mr. Toots ties a string around his troublesome tooth and attaches it to a heavy book. In a moment of sudden inspiration mixed with frustration, he successfully extracts the tooth by throwing the book, but his relief quickly turns to anger as he hurls the book toward his staff in a fit of rage. The film concludes with Mr. Toots finally free from his dental agony, having found an unconventional solution to his suffering.

About the Production

This was one of the many comedy shorts produced by Thanhouser during their peak production years. The film was likely shot in just one or two days, as was typical for short comedies of this era. The production utilized simple sets and props, focusing on physical comedy and slapstick elements that were popular with audiences of the time.

Historical Background

1913 was a transformative year in American cinema, marking the transition from the nickelodeon era to the age of the movie palace. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with independent studios like Thanhouser competing against the Motion Picture Patents Company (the Edison Trust). This period saw the emergence of the star system, though many actors were still uncredited in films. The United States was experiencing rapid industrialization and urbanization, and movies served as both entertainment and escapism for working-class audiences. Silent comedies like 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' were particularly popular as they transcended language barriers and appealed to diverse immigrant audiences in urban centers. The film was released just a year before World War I began in Europe, which would dramatically impact international film production and distribution.

Why This Film Matters

While 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' may seem simple by modern standards, it represents an important stage in the development of American film comedy. The film exemplifies the physical comedy tradition that would evolve into the sophisticated slapstick of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd. It demonstrates how early filmmakers were already exploring universal human experiences like pain and frustration for comedic effect. The toothache scenario reflects everyday struggles that audiences could relate to, making the humor accessible across cultural and class boundaries. This film also illustrates the transition from stage comedy techniques to the new medium of cinema, where visual storytelling and physical gags became paramount. The preservation of such films provides valuable insight into early 20th-century humor, social norms, and the evolution of cinematic language.

Making Of

The production of 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' exemplifies the rapid-fire production methods of early American cinema. Thanhouser Film Corporation, like many studios of the era, operated on a factory-like system, churning out multiple short films each week to meet the insatiable demand from nickelodeons and movie theaters. The film was likely shot on a simple set with minimal lighting equipment, as studios of this period often relied on natural light from glass ceilings or windows. The physical comedy required precise timing from Arthur Housman, who had to convey pain and frustration through exaggerated gestures and facial expressions without the benefit of dialogue. The tooth-pulling scene would have required careful coordination to achieve the comedic effect while ensuring the actor's safety. Director Charles M. Seay, working with a small crew, would have had to complete shooting in just a few hours to maintain the studio's production schedule.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' reflects the technical limitations and conventions of 1913 filmmaking. The film was likely shot on 35mm film using hand-cranked cameras, resulting in variable frame rates that could create slightly jerky motion. The lighting would have been primarily natural, possibly supplemented by arc lights if shooting indoors. The camera positioning would have been relatively static, with wide shots to capture the actors' full physical movements, as close-ups were still being developed as a cinematic technique. The film stock of the era was orthochromatic, which rendered colors in limited tones and affected how actors' makeup appeared on screen. The cinematographer would have focused on ensuring clear visibility of the physical comedy and facial expressions that were crucial for silent storytelling.

Innovations

While 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' does not represent major technical innovations, it demonstrates the standard production techniques of the maturing film industry in 1913. The film showcases the effective use of continuity editing to maintain narrative flow across different shots and scenes. The physical comedy required careful choreography and timing to achieve maximum comedic effect within the technical constraints of the era. The film represents the refinement of gag structure in comedy shorts, with setup, escalation, and payoff clearly communicated through visual means. The production likely utilized the increasingly standardized equipment and workflows that were making film production more efficient and consistent across the industry.

Music

As a silent film, 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original theatrical run, the film would have been accompanied by live music provided by the theater's pianist or organist. The accompaniment would have been selected from standard musical libraries or improvised by the musician to match the on-screen action. For a comedy like this, the music would likely have been light and playful, with more frantic passages during the tooth-pulling sequence. Some theaters might have used sound effects created by backstage crew members to enhance the comedy, such as crashing sounds when the book was thrown. The lack of fixed audio allowed for variation in presentation from theater to theater, with each venue providing its own unique interpretation of the film's mood.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic tooth-pulling scene where Mr. Toots ties a string to his tooth and a book, then successfully extracts the tooth by throwing the book at his staff in frustration.

Did You Know?

- This film was part of Thanhouser's comedy series, one of the many short subjects they produced weekly for theaters.

- Director Charles M. Seay was not only a director but also appeared as an actor in numerous films during this period.

- The tooth-pulling gag using a string and heavy object was already a classic comedy routine by 1913, having been used in vaudeville and earlier films.

- Arthur Housman, who plays Mr. Toots, would later become famous for his recurring role as 'The Drunk' in numerous comedy films of the 1920s and 1930s.

- The film was released during the height of the single-reel era, when most comedies were approximately 10 minutes long to fit on one reel of film.

- Thanhouser Film Corporation was one of the early independent film studios that competed with Edison's Trust.

- The film's physical comedy style reflects the influence of French comedian Max Linder, who was hugely popular in America during this period.

- 1913 was a pivotal year in cinema, marking the transition from short subjects to longer feature films.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of short films like 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' were typically brief and appeared in trade publications rather than mainstream newspapers. The film was likely reviewed in publications like The Moving Picture World or The New York Dramatic Mirror, where it would have been assessed primarily on its entertainment value and technical execution. Critics of the era often praised films that provided good clean entertainment and demonstrated technical competence. Modern film historians view such works as important artifacts that document the development of comedy techniques and the early film industry's production methods. The film is now appreciated by silent film enthusiasts for its representation of early American comedy and its role in the career development of its cast and crew.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1913 would have received 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' as light entertainment during a program of multiple short films. The physical comedy and relatable scenario of dealing with a toothache would have resonated with working-class viewers who attended nickelodeons regularly. The exaggerated acting style was expected and appreciated in silent cinema, as it helped convey emotions and actions without dialogue. The film's brief runtime made it ideal for the short attention spans of early cinema audiences. The tooth-pulling gag, already familiar from vaudeville, would have been anticipated and enjoyed by viewers. While specific audience reactions to this particular film are not documented, comedy shorts were consistently popular and drew repeat customers to theaters during this period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French comedies of Max Linder

- American vaudeville traditions

- Mack Sennett comedy style

- Chaplin's early tramp films

This Film Influenced

- Later dental comedy shorts

- Three Stooges tooth extraction routines

- Laurel and Hardy medical comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Mr. Toots' Tooth' is unclear, as is the case with many Thanhouser shorts from this period. Many films from the 1910s have been lost due to the decomposition of nitrate film stock. The Thanhouser Company Film Preservation Archive has worked to recover and preserve many of the studio's films, but not all productions have survived. The film may exist in archives or private collections, or it may be among the lost films of the era. Silent film enthusiasts and archives continue to search for missing films from this period.