Night of the Hunchback

"A night of mischief, mayhem, and one very inconvenient corpse"

Plot

In this dark comedy adapted from One Thousand and One Nights, a hunchbacked actor dies during a performance, setting off a chain of increasingly absurd events. The actors who discover his body panic and attempt to dispose of it secretly, leading to a series of misadventures as the corpse changes hands multiple times throughout the night. Each person who comes into possession of the body faces their own moral dilemma and comedic predicament while trying to get rid of it. The situation spirals into farce as more people become involved, each with their own motivations and fears about being implicated in the death. The film satirizes social hypocrisy and human nature through the characters' increasingly desperate attempts to avoid responsibility. Ultimately, the night's events reveal deeper truths about guilt, community, and the absurdity of social conventions.

About the Production

Shot in black and white on a minimal budget, the film faced censorship challenges due to its satirical content and dark themes. Director Farrokh Ghaffari both directed and acted in the film, a common practice in early Iranian independent cinema. The production utilized limited sets and natural lighting to create an atmosphere of claustrophobia and tension. The film was completed over a period of several months due to funding constraints and the need to work around censorship requirements.

Historical Background

Night of the Hunchback was produced during a pivotal period in Iranian history, the mid-1960s, when Iran was undergoing rapid modernization under the White Revolution. This era saw significant social and economic changes, including land reforms, women's suffrage, and industrialization, which created tensions between traditional values and modern influences. The film industry was also in transition, moving away from commercial 'Filmfarsi' productions toward more artistic and socially conscious cinema. Ghaffari, as an intellectual who had studied abroad, represented this new wave of Iranian filmmakers who sought to create cinema that could compete internationally while addressing Iranian social issues. The film's release coincided with increased government scrutiny of artistic expression, making its satirical take on social hypocrisy particularly bold. The 1960s also saw the growth of Iranian film criticism and film societies, which provided an audience for more experimental works like this. The film's adaptation of a classic Persian story for modern cinema reflected broader debates in Iranian intellectual circles about how to reconcile cultural heritage with modernity.

Why This Film Matters

Night of the Hunchback holds a significant place in Iranian cinema history as one of the pioneering works of the Iranian New Wave movement. The film demonstrated that Iranian cinema could address complex social issues through sophisticated narrative techniques, moving beyond the simplistic melodramas that dominated the industry at the time. Its successful adaptation of a classic Persian story into a modern cinematic language showed how traditional cultural elements could be reimagined for contemporary audiences. The film's dark comedy approach to social criticism paved the way for later Iranian filmmakers to use satire as a tool for social commentary. Its international festival recognition helped establish Iranian cinema on the world stage, proving that Iranian films could appeal to global audiences while maintaining their cultural specificity. The film's themes of social hypocrisy and individual responsibility resonated with Iranian intellectuals and artists who were navigating the complex social changes of the 1960s. Its influence can be seen in later Iranian films that blend comedy with social criticism, from the works of Abbas Kiarostami to contemporary Iranian filmmakers. The film remains a touchstone for discussions about the relationship between tradition and modernity in Iranian art.

Making Of

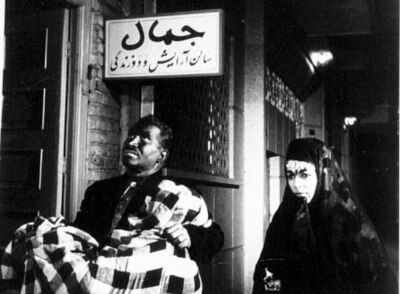

The production of Night of the Hunchback was marked by significant challenges, both financial and political. Director Farrokh Ghaffari, who had studied cinema in France, brought European cinematic techniques to Iranian storytelling, creating a unique blend of Persian narrative traditions with modern film language. The cast was composed largely of theater actors transitioning to cinema, which contributed to the film's exaggerated performance style. Shooting often took place at night to avoid interference from authorities and to accommodate the actors' theater schedules. The film's dark comedic tone was revolutionary for Iranian cinema of the 1960s, which typically focused on melodrama or historical epics. Ghaffari had to fight with censors throughout the production process, ultimately having to make significant cuts to secure a release certificate. The film's limited budget meant that many scenes had to be improvised, with the crew using whatever locations and props were available. Despite these constraints, Ghaffari managed to create a visually striking film that used shadow and light to enhance its macabre atmosphere.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, shot in stark black and white, creates a shadowy, expressionistic atmosphere that enhances its dark comedic tone. Cinematographer Davud Mollapour utilized chiaroscuro lighting techniques to create visual tension and highlight the moral ambiguity of the characters' actions. The camera work often employs Dutch angles and unusual perspectives to emphasize the absurdity of situations and the psychological states of the characters. Long takes are used effectively to build comedic tension, particularly in scenes involving the disposal of the body. The film makes strategic use of close-ups to capture the characters' panicked expressions and internal conflicts. The visual style shows influences from German Expressionism and Italian neorealism, adapted to the Iranian context. The limited studio locations are transformed through creative lighting and camera work to create a sense of urban claustrophobia. The cinematography also incorporates elements of traditional Persian visual arts in its composition, particularly in its use of geometric patterns and framing.

Innovations

Night of the Hunchback achieved several technical innovations for Iranian cinema of its era. The film's sound design was particularly advanced, using creative audio techniques to enhance the comedic timing and tension of key scenes. The editing, while constrained by limited resources, employed sophisticated jump cuts and montage sequences that were unusual for Iranian cinema at the time. The film's makeup effects for the corpse were remarkably realistic given the budget constraints, using innovative techniques that became influential in Iranian horror and comedy productions. The cinematography achieved impressive results with limited lighting equipment, creating atmospheric effects that enhanced the film's dark tone. The production design made creative use of limited sets, transforming simple locations through clever camera work and lighting. The film's post-production techniques, particularly in sound mixing and dubbing, were innovative for Iranian cinema of the 1960s. The film demonstrated how technical limitations could be turned into artistic advantages, influencing subsequent generations of Iranian filmmakers working with minimal resources.

Music

The film's score was composed by Ahmad Pejman, one of Iran's pioneering film composers who blended Western classical traditions with Persian musical elements. The soundtrack features a minimalist approach, using sparse instrumentation to enhance the film's tense and absurd atmosphere. Traditional Persian instruments such as the santur and tar are incorporated subtly into the score, creating a cultural resonance that grounds the story in its Iranian context. The music often uses ironic juxtapositions, playing light, almost circus-like themes during dark moments to enhance the black comedy effect. Sound design is particularly important in the film, with exaggerated diegetic sounds used to emphasize the physical comedy and the characters' mounting panic. The limited budget meant that much of the music had to be recorded with small ensembles, but this constraint actually contributed to the score's intimate and unsettling quality. The film's soundtrack was innovative for its time in Iranian cinema, moving away from the lush orchestral scores typical of the period toward something more experimental and atmospheric.

Famous Quotes

In the darkness of night, all truths become visible, and all lies become heavy as a corpse.

A dead man has no rights, but he has many responsibilities for the living.

In this city, we carry our sins like we carry our dead - secretly, quickly, and always looking over our shoulders.

The night is long enough to bury one body, but not long enough to bury one's conscience.

In Tehran, even the dead must learn to navigate bureaucracy and social hierarchy.

We are all actors in this theater of life, but some of us forget when the curtain falls.

The hunchback carries more than his physical burden - he carries the weight of our pretensions.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening theater scene where the hunchback actor dies mid-performance, with the audience initially believing it's part of the show, creating a moment of tragicomic confusion that sets the tone for the entire film.

- The rooftop sequence where characters attempt to lower the body from a building using bedsheets, only to have it get stuck and be discovered by neighbors, leading to a frantic chase through the alleyways of Tehran.

- The funeral home scene where the characters must pretend to be grieving relatives while trying to explain the unusual circumstances of the death to a suspicious undertaker.

- The climactic scene in the public square where the body is finally discovered by authorities, and all the characters must face the consequences of their night of deception.

- The final scene where the remaining characters gather in a tea house, silently contemplating their experiences as the morning light reveals the city waking up to another day, unchanged by the night's events.

Did You Know?

- Farrokh Ghaffari was not only the director but also a pioneering figure in Iranian cinema, having founded Iran's first film club and film archive

- The film is one of the earliest examples of Iranian black comedy, a genre that would later flourish in Iranian cinema

- Despite its modest budget, the film was selected for screening at several international film festivals, helping introduce Iranian cinema to global audiences

- The hunchback character was played by Farhang Amiri, who was known for his physical acting abilities and had previously worked in traditional Persian theater

- The film's script was heavily censored by Iranian authorities before approval, requiring multiple revisions to remove politically sensitive content

- Night of the Hunchback was one of the first Iranian films to directly address themes of social hypocrisy and class divisions through dark comedy

- The film was banned in Iran for several years after its initial release due to its controversial themes

- Director Ghaffari was influenced by Italian neorealism and French New Wave cinema, which is evident in the film's visual style and narrative approach

- The corpse prop used in the film became legendary among Iranian film crews for its remarkably realistic appearance

- The film's original Persian title was 'Shab-e Gholbakhteh,' which translates literally to 'Night of the Hunchbacked One'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Night of the Hunchback for its bold approach to social satire and its sophisticated cinematic techniques. Iranian film critics of the 1960s hailed it as a breakthrough for national cinema, particularly noting Ghaffari's skill in blending Persian storytelling traditions with modern film language. International critics at film festivals were impressed by the film's unique tone and its ability to address universal themes through a specifically Iranian cultural lens. The film's black comedy elements were particularly noted as innovative for Iranian cinema of the period. Over time, film scholars have come to recognize it as a key work in the Iranian New Wave, analyzing its techniques for subverting censorship while delivering social commentary. Modern critics appreciate the film's historical importance and its role in establishing the possibility of satirical cinema in Iran. Some contemporary reviews note that while the film's techniques may seem dated by modern standards, its themes and humor remain remarkably relevant. The film is now studied in film schools as an example of how cinema can navigate political constraints while maintaining artistic integrity.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception to Night of the Hunchback was mixed, reflecting the film's challenging nature for mainstream Iranian viewers of the 1960s. Traditional cinema-goers found the dark comedy elements unsettling, as they were accustomed to more straightforward melodramas and comedies. However, educated urban audiences and intellectuals embraced the film's sophisticated approach to social criticism. The film developed a cult following among Iranian cinephiles, particularly those who frequented the growing film club scene in Tehran. International audiences at film festivals responded positively to the film's unique blend of humor and social commentary. Over the decades, the film's reputation has grown among cinema enthusiasts, with many considering it an overlooked masterpiece of early Iranian art cinema. The film's limited availability due to censorship and distribution challenges has made it somewhat of a legend among Iranian film historians. Modern Iranian audiences who have discovered the film through retrospectives and special screenings often express surprise at its boldness and contemporary relevance. The film's status as a banned work for many years has added to its mystique and cultural significance.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Director at the Sepas Film Festival, Tehran (1966)

- Special Jury Prize at the Moscow International Film Festival (1966)

- Best Black Comedy at the Asian Film Festival (1967)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism (particularly the works of Federico Fellini)

- French New Wave cinema

- German Expressionist film

- Traditional Persian theater (Ta'zieh and Ruhowzi)

- One Thousand and One Nights folk tales

- The comedy of errors tradition

- Brechtian theater techniques

- Film noir visual style

This Film Influenced

- The Cow (1969, Dariush Mehrjui)

- Still Life (1974, Sohrab Shahid-Saless)

- The Cycle (1975, Dariush Mehrjui)

- The Report (1977, Abbas Kiarostami)

- The Tenants (1986, Kamal Tabrizi)

- A Separation (2011, Asghar Farhadi)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Night of the Hunchback was considered partially lost for many years due to poor storage conditions and political neglect. Original negatives were damaged during the Iranian Revolution, but several prints survived in international archives, particularly at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris. The film was restored in 2015 by the Iranian Film Archive in collaboration with the World Cinema Foundation, using surviving elements from various international sources. The restoration process was challenging due to the degraded condition of available materials, but the film has now been preserved in 4K digital format. Some scenes remain incomplete or of lower quality due to the loss of original elements. The restored version premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2016 and has since been screened at various retrospective events worldwide. The film is now part of the permanent collection at several major film archives, including the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art's film department.