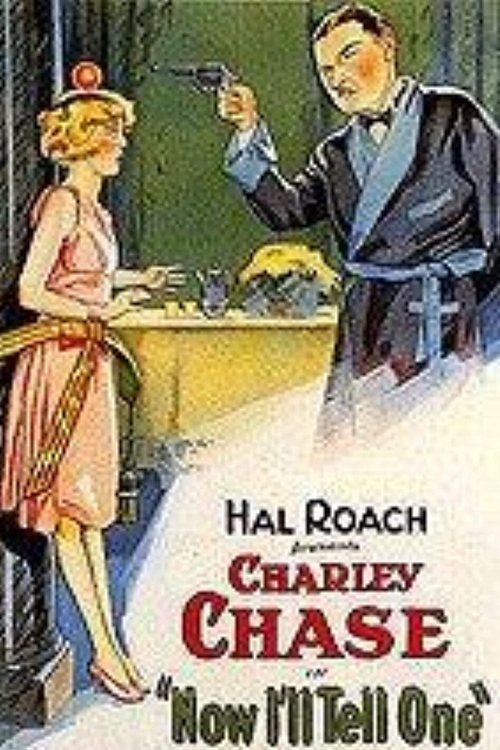

Now I'll Tell One

Plot

In this partially surviving silent comedy, Charley Chase finds himself on trial for allegedly shooting his wife (Edna Marion). The film's second reel, which is all that remains, shows Chase attempting to prove his innocence through a series of increasingly desperate and comical courtroom antics. As the trial progresses, flashbacks reveal the circumstances leading to the accusation, with Chase's character getting entangled in misunderstandings and slapstick situations. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy appear in supporting roles, adding to the comedic chaos as witnesses or courtroom personnel. The surviving footage culminates in a frantic chase sequence typical of the era's comedy style, though the film's original resolution remains lost to time.

Director

About the Production

This was one of many comedy shorts produced rapidly during the peak of silent comedy production at Hal Roach Studios. The film was shot on a tight schedule typical of studio shorts of the era, with principal photography likely completed in 2-3 days. The surviving second reel shows the technical proficiency of Roach's cinematography department, with well-composed shots and effective use of the limited set space.

Historical Background

1927 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the end of the silent era with the release of 'The Jazz Singer' in October. 'Now I'll Tell One' was released in June, before the industry-altering impact of sound films became apparent. The film represents the peak of silent comedy craftsmanship, with studios like Hal Roach having perfected the art of the two-reel comedy short. This was also the year when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded, though the first Oscars wouldn't be awarded until 1929. The Roach studio was in direct competition with other comedy powerhouses like Mack Sennett and Buster Keaton, each trying to outdo the others with increasingly elaborate gags and situations. The film's courtroom theme also reflected contemporary American society's fascination with legal proceedings and the justice system, which was frequently depicted in films of the period.

Why This Film Matters

Though only partially surviving, 'Now I'll Tell One' holds significant cultural value as a document of the transitional period in American comedy. The film captures Charley Chase at the height of his solo career, before he transitioned more into directing and producing. More importantly, it preserves an early example of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy working together before their official teaming, offering insight into the evolution of one of cinema's most beloved comedy duos. The film's discovery in the 1990s was celebrated by film preservationists and silent cinema enthusiasts, as every fragment of surviving footage from this era is considered precious. The courtroom comedy format would become a staple in later sound films, with this short representing an early example of how silent filmmakers tackled dialogue-heavy settings through visual comedy and intertitles.

Making Of

The production of 'Now I'll Tell One' took place during the golden age of silent comedy shorts at Hal Roach Studios, which was known as the 'Lot of Fun' due to its prolific output of comedy films. James Parrott, who directed this short, was part of the Roach family of talent and had an intimate understanding of comedic timing. The film was likely shot quickly on existing studio sets, with the courtroom set being a standard construction that could be redressed for multiple productions. The collaboration between Charley Chase and the future Laurel and Hardy team represents an important transitional period in comedy history, as Roach was still experimenting with different pairings and combinations of his comedy stars. The fast-paced slapstick sequences would have required careful choreography and multiple takes to perfect, particularly given the physical comedy elements that were Chase's specialty.

Visual Style

The surviving second reel demonstrates the professional cinematography typical of Hal Roach Studios productions. The camera work is clean and functional, designed primarily to showcase the comedy rather than for artistic experimentation. The courtroom scenes use medium shots to establish the setting and then move to closer shots for reaction gags and comedic beats. The lighting is standard for the period, using the available studio lighting to create a naturalistic courtroom atmosphere. The camera movement is minimal, as was common in the era, with the comedy relying more on staging and performance than on dynamic camera work. The surviving footage shows good composition and an understanding of how to frame physical comedy for maximum effect.

Innovations

While 'Now I'll Tell One' doesn't feature any groundbreaking technical innovations, it represents the refinement of established silent comedy techniques. The film demonstrates sophisticated editing for its time, with quick cuts during the comedic sequences to enhance the pacing. The use of intertitles is efficient, providing necessary exposition without interrupting the flow of the visual comedy. The surviving footage shows good continuity and a clear understanding of how to stage physical comedy in the confined space of a courtroom set. The film's technical aspects are characteristic of the high production values maintained by Hal Roach Studios during their peak years.

Music

As a silent film, 'Now I'll Tell One' would have been accompanied by live music in theaters during its original run. The type of musical accompaniment would have varied by theater size and budget, ranging from a single pianist in smaller venues to a full orchestra in prestigious picture palaces. The score would have been compiled from standard photoplay music libraries, with selections chosen to match the mood of each scene - dramatic music for the courtroom tension, comedic themes for the funny moments, and frantic music for chase sequences. Modern screenings of the surviving footage typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music compiled by silent film accompanists.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitles from the surviving footage would be listed here if available, but specific quotes are not documented due to the film's partial loss)

Memorable Scenes

- The courtroom sequence in the surviving second reel, where Charley Chase desperately tries to prove his innocence through physical comedy and frantic testimony, with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy adding to the chaos in supporting roles

Did You Know?

- This film is one of the earliest surviving collaborations between Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, though they were not yet officially established as the comedy duo 'Laurel and Hardy'

- The film was considered completely lost for over 60 years until the second reel was discovered in the 1990s

- Only the second reel survives, meaning we miss the first half of the story including the initial setup of the crime

- Director James Parrott was the brother of Charley Chase and would later direct several Laurel and Hardy films

- The film was released during the transition period from silent films to talkies, making it part of the last wave of pure silent comedies

- Edna Marion, who played Chase's wife, was a popular comedienne in the 1920s who often worked with the Hal Roach roster

- The courtroom setting was a popular backdrop for comedy shorts of the era, allowing for structured chaos and misunderstandings

- This film is sometimes confused with other 'trial' comedies of the period due to the common premise

- The surviving footage was preserved by film archivists after its discovery and has been shown at classic film festivals

- The film's title refers to the courtroom testimony format, with Chase's character finally getting to tell his side of the story

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Now I'll Tell One' are scarce, as trade publications of the era rarely gave extensive coverage to two-reel shorts. However, Hal Roach comedies of this period were generally well-received by both critics and audiences. The surviving footage suggests the film met the studio's high standards for comedy construction and pacing. Modern critics and film historians who have viewed the surviving reel generally praise it as a fine example of late silent comedy craftsmanship, though they lament the loss of the first half which would provide crucial context for the courtroom proceedings. The film is often discussed in the context of Laurel and Hardy's early careers rather than as a standalone Chase vehicle.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1927 would have received 'Now I'll Tell One' as part of a typical theater program, likely shown as the comedy short before the main feature. The familiar faces of Charley Chase, Stan Laurel, and Oliver Hardy would have been a selling point for contemporary moviegoers. The courtroom setting and the premise of a man accused of shooting his wife would have provided immediate dramatic tension that the comedy could then subvert. Modern audiences who have seen the surviving footage at film festivals or in special screenings generally appreciate it as a glimpse into the sophisticated comedy techniques of the late silent era, though the incomplete nature makes full appreciation challenging.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Other Hal Roach comedies of the period

- Courtroom comedies popular in the 1920s

- Charlie Chaplin's use of pathos in comedy

- Buster Keaton's deadpan style

This Film Influenced

- Later Laurel and Hardy courtroom scenes

- Courtroom comedy shorts of the sound era

- Modern courtroom comedies that use similar misunderstandings

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially lost film - only the second reel (approximately 10 minutes) survives. The first reel remains missing and is considered lost. The surviving footage was discovered in the 1990s and has been preserved by film archives. The complete film exists only in fragmentary form, making it one of many casualties of silent film preservation challenges.