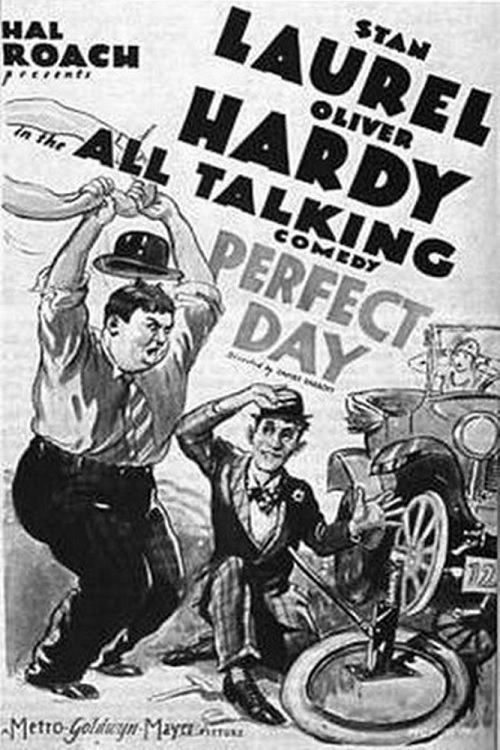

Perfect Day

Plot

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy attempt to enjoy a peaceful Sunday picnic with their families, but their plans are continuously sabotaged by a series of automotive disasters. The film centers on the recurring gag of the family repeatedly having to exit and re-enter their temperamental car as each new problem arises, from flat tires to engine failures. The situation is exacerbated by Oliver's mother-in-law's constant complaints and Uncle Edgar's severe gout, which makes him increasingly irritable with each interruption. Despite their best efforts to maintain composure and solve each mechanical problem, the couple's idyllic day out devolves into chaos. The comedy builds through the mounting frustration of the characters and the absurd repetition of their failed attempts to begin their journey, culminating in a final disastrous mishap that completely derails their picnic plans.

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during the critical transition period from silent to sound cinema. Like many Hal Roach productions of 1929, it was filmed in both silent and sound versions to accommodate theaters that had not yet converted to sound equipment. The sound version featured synchronized music, sound effects, and limited dialogue, while the silent version relied on title cards and musical accompaniment provided by theater orchestras. The repetitive car gag required precise timing and coordination between the actors and the technical crew to maintain comedic rhythm throughout multiple takes.

Historical Background

1929 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the full transition from the silent era to the sound age. The stock market crash of October 1929 occurred just months after this film's release, heralding the Great Depression that would dramatically affect the film industry. Despite the economic turmoil, comedy films like 'Perfect Day' remained popular as audiences sought escape from their daily troubles. The film was produced during the height of the Laurel and Hardy partnership, which had been officially established in 1927 and was reaching its peak popularity. This period saw the duo becoming international stars, with their films being distributed worldwide. The automotive theme was particularly relevant in 1929, as car ownership was becoming increasingly common among middle-class Americans, making the frustrations depicted in the film relatable to contemporary audiences. The film's release also coincided with the establishment of the Academy Awards, which had been founded the previous year, though comedy shorts were not yet recognized as a separate category.

Why This Film Matters

'Perfect Day' represents a quintessential example of early sound comedy and showcases the genius of Laurel and Hardy's collaborative chemistry. The film exemplifies the duo's formula of contrasting personalities - Laurel's childlike innocence versus Hardy's frustrated authority - which would influence countless comedy teams that followed. The automobile as a source of comedy became a recurring theme in early sound films, reflecting society's growing dependence on and frustration with new technology. The film's structure, built around a single escalating comedic premise, demonstrated how sound could enhance visual comedy rather than replace it, a lesson that was crucial for comedians transitioning from silent films. Edgar Kennedy's performance as the perpetually aggravated uncle helped establish the 'slow burn' comedy archetype that would become a staple of American comedy. The film also captures the American ideal of the family outing and the Sunday picnic, cultural touchstones of the era, while simultaneously satirizing the technological optimism of the 1920s.

Making Of

The production of 'Perfect Day' took place during one of the most tumultuous periods in Hollywood history - the transition from silent films to sound. The Hal Roach Studios, like other major studios of the era, was racing to convert to sound technology while still producing content for theaters that hadn't made the switch. This meant shooting scenes twice in many cases - once for the silent version and once with sound equipment. The car gag required extensive rehearsals to perfect the timing of the actors' movements, as each family member had to coordinate their exits and re-entries to maximize comedic effect. Stan Laurel, known for his meticulous attention to comedic details, reportedly spent hours working on the physical timing of each gag. Edgar Kennedy, a veteran comedian who had worked with Charlie Chaplin, developed his distinctive 'slow burn' reaction style during the filming of this short, which would become his trademark in future roles. The production faced additional challenges from the primitive sound recording equipment of the era, which was bulky and sensitive to movement, limiting the camera's mobility and requiring the actors to stay relatively stationary during dialogue scenes.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens employs relatively static camera positions typical of early sound films, due to the limitations of the bulky sound recording equipment. The visual composition focuses on clear framing of the comedic action, particularly the repeated gag of the family entering and exiting the automobile. Stevens uses medium shots to capture the full body language of the performers, which was crucial for conveying emotion and comedy in the early sound era. The exterior scenes benefit from natural lighting, creating a bright, cheerful atmosphere that contrasts ironically with the characters' mounting frustrations. The camera work emphasizes the spatial relationships between the characters and their problematic vehicle, using depth of field to maintain visual clarity throughout the complex group scenes. The cinematography successfully balances the technical requirements of early sound filming with the visual comedy traditions established during the silent era.

Innovations

While 'Perfect Day' was not groundbreaking in terms of technical innovation, it represents a successful application of early sound technology to comedy. The film demonstrated how synchronized sound could enhance rather than hinder visual comedy, a crucial lesson during the transition from silent films. The production team effectively managed the technical challenges of recording both dialogue and sound effects in an era when such recording was still primitive and unreliable. The film's use of repetitive gags with sound variations showed an early understanding of how audio could be used to create comedic rhythm and timing. The dual production process - creating both silent and sound versions - required careful planning and resource management, showcasing the studio's adaptability during this transitional period. The sound design, particularly the automotive effects, was notably effective for its time, helping to create a believable world of mechanical frustration that audiences found relatable and hilarious.

Music

The sound version of 'Perfect Day' featured a synchronized musical score composed by Leroy Shield, who created many of the memorable themes for Hal Roach productions. The soundtrack included popular songs of the era as well as original comedic musical cues that enhanced the on-screen action. Sound effects were carefully synchronized with the visual gags, particularly the various automotive malfunctions that drive the plot. The limited dialogue was recorded using early microphone technology, resulting in the somewhat flat audio quality typical of 1929 sound films. The musical accompaniment included jaunty, optimistic themes that played ironically against the characters' mounting frustrations. For the silent version, theaters would have provided their own musical accompaniment, typically using cue sheets supplied by the studio to ensure appropriate music for each scene. The soundtrack represents an early example of how music and sound effects could enhance physical comedy without overwhelming it.

Famous Quotes

Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!

Why don't you do something to help?

This is a perfect day for a picnic... if we ever get started!

My gout is killing me! Can't you do anything right?

Now everybody back in the car... wait, what's that noise?

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic sequence where the entire family repeatedly gets in and out of the car, each time discovering a new problem that needs fixing, building comedic tension through the mounting repetition of the action.

- Uncle Edgar's increasingly frustrated reactions to each interruption, his face growing redder and his patience wearing thinner with each mechanical failure.

- The final disastrous moment when the car completely falls apart, leaving the family stranded and their picnic dreams shattered in a spectacular display of automotive failure.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first Laurel and Hardy films to be released with a synchronized soundtrack, though it was not a full 'talkie'

- The film was remade in 1932 as 'Scram!' with a slightly different plot but similar automotive frustration themes

- Edgar Kennedy's character of the gout-ridden uncle became so popular that it led to his own series of comedy shorts at RKO Pictures

- The car used in the film was a 1920s-era Ford Model T, chosen specifically for its reputation for mechanical unreliability

- The repeated gag of the family getting in and out of the car was inspired by a similar routine in Harold Lloyd's 1924 film 'Girl Shy'

- The film was shot in just three days, typical for Hal Roach comedy shorts of the era

- The original script included additional scenes that were cut to maintain the brisk pacing required for comedy short format

- The sound version featured a popular song of the era, 'Perfect Day,' which may have inspired the film's title

- This was one of the last Laurel and Hardy films directed by James Parrott before he focused primarily on writing

- The film's success led to several similar 'frustrated journey' comedies starring the duo throughout the early 1930s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Perfect Day' for its successful transition to sound while maintaining the visual comedy that made Laurel and Hardy famous. The New York Times noted that 'the addition of sound has not diminished the duo's comedic timing, but rather enhanced their already hilarious situations.' Variety magazine highlighted the film's 'perfect pacing and expert execution of the recurring automobile gag.' Modern critics and film historians view the short as a classic example of early sound comedy, with Leonard Maltin describing it as 'one of Laurel and Hardy's most perfectly constructed shorts.' The film is often cited in scholarly works about the transition from silent to sound cinema as an example of how comedy successfully adapted to the new medium. The British Film Institute includes it in their list of essential Laurel and Hardy films, noting its 'masterful blend of physical comedy and sound effects.'

What Audiences Thought

Audiences of 1929 embraced 'Perfect Day' enthusiastically, finding both humor and relatability in the automotive mishaps depicted. The film was a popular attraction in theaters across the United States and did particularly well in smaller towns where car ownership was becoming more common but mechanical problems remained a frequent frustration. Contemporary audience reports from the era indicate that the repeated gag of the family getting in and out of the car generated increasing laughter with each repetition, as viewers anticipated the next disaster. The film's success was evident in its continued theatrical run, which was longer than typical for comedy shorts of the period. International audiences also responded positively, with the film proving popular in Europe where Laurel and Hardy had developed a substantial following. Modern audiences continue to appreciate the film's timeless humor, with it frequently appearing in Laurel and Hardy film festivals and retrospective screenings. The short's availability on home video and streaming platforms has introduced it to new generations, maintaining its popularity nearly a century after its initial release.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Harold Lloyd's 'Girl Shy' (1924) - for the repetitive gag structure

- Buster Keaton's 'The General' (1926) - for mechanical comedy

- Charlie Chaplin's 'The Gold Rush' (1925) - for character-driven humor

- Previous Laurel and Hardy shorts - for establishing their character dynamics

This Film Influenced

- Laurel and Hardy's 'Scram!' (1932) - remake with similar themes

- The Three Stooges' 'Pardon My Scotch' (1935) - for repetitive frustration comedy

- Abbott and Costello's 'Hold That Ghost' (1941) - for escalating problem structure

- Modern comedy films featuring automotive disasters

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved in both its silent and sound versions. The Library of Congress maintains 35mm prints in their collection, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive holds additional materials. The film has been digitally restored as part of various Laurel and Hardy collections, with the sound version receiving particular attention for audio cleanup. Both versions survive in excellent condition, allowing modern audiences to appreciate the film as it was originally intended to be seen.