Rabindranath Tagore

Plot

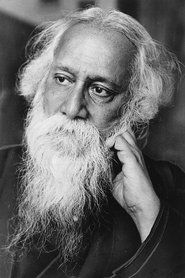

Satyajit Ray's documentary 'Rabindranath Tagore' is a masterful exploration of the life and legacy of India's Nobel laureate, created during Tagore's birth centenary year. The film traces Tagore's journey from his childhood in the Jorasanko mansion to his evolution as a poet, philosopher, musician, painter, and social reformer who reshaped Bengali literature and Indian art. Ray employs a unique blend of archival photographs, rare footage, paintings, and carefully reconstructed scenes to bring Tagore's multifaceted personality to life. The documentary delves into Tagore's philosophical outlook, his travels around the world, his educational experiments at Santiniketan, and his complex relationship with modernity and tradition. Through Ray's lens, viewers witness how Tagore became the first non-European and first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, while also exploring his deep connection to nature, his spiritual quest, and his vision for a universal humanism.

About the Production

Ray faced the challenge of creating a documentary about a figure who was both deeply revered and complex in his multifaceted genius. He spent months researching Tagore's life, collecting rare photographs, paintings, and archival materials from various sources including the Tagore family. The film was commissioned by the Government of India as part of the nationwide centenary celebrations of Tagore's birth. Ray's innovative approach included using Tagore's own paintings and photographs as visual elements, combined with his evocative narration and carefully selected musical pieces composed by Tagore himself. The production team had to work with limited archival footage, leading Ray to create dramatic reconstructions of key moments from Tagore's life.

Historical Background

The film was created in 1961, exactly 100 years after Tagore's birth and 14 years after India's independence. This was a period of intense nation-building in India, when the country was actively defining its cultural identity and place in the world. Tagore's centenary was not just a cultural event but a national celebration of one of the figures who had helped shape modern Indian consciousness. The early 1960s also saw the rise of Indian parallel cinema, with Satyajit Ray emerging as its most prominent voice internationally. The documentary was part of a larger government initiative to preserve and promote India's cultural heritage, reflecting the post-colonial emphasis on reclaiming and celebrating indigenous intellectual traditions. The film emerged during the Cold War era, when Tagore's message of universal humanism and East-West synthesis was particularly relevant to global discourse.

Why This Film Matters

Ray's documentary played a crucial role in introducing Rabindranath Tagore to international audiences at a time when the poet's global recognition was waning outside South Asia. The film helped revive interest in Tagore's works and philosophy, particularly his visual art which had been largely overlooked. Within India, the documentary became an educational tool used in schools and universities to teach about Tagore's contributions to literature, music, and art. Ray's approach to documentary filmmaking influenced a generation of Indian documentary filmmakers, showing how artistic sensibility could elevate non-fiction cinema. The film also demonstrated how documentary could serve as a bridge between high art and popular culture, making Tagore's complex ideas accessible to ordinary viewers. Its success paved the way for more artistic documentaries on Indian cultural figures and helped establish documentary as a legitimate form of artistic expression in Indian cinema.

Making Of

Satyajit Ray approached this documentary with the same meticulous attention to detail that characterized his narrative films. He spent months researching Tagore's life, visiting the Tagore archives at Santiniketan and consulting with scholars and family members. Ray's challenge was to create a portrait that was both reverential and honest, avoiding hagiography while capturing Tagore's revolutionary spirit. The director used a combination of techniques - slow pans across photographs, careful selection of archival footage, and his own poetic narration - to create a meditative, contemplative mood. Ray was particularly interested in Tagore's visual art, and he gave significant screen time to Tagore's paintings, which were relatively unknown to the general public at the time. The documentary's production coincided with Ray's growing international reputation, and he brought his newfound cinematic sophistication to this project, elevating it beyond a typical government-commissioned documentary.

Visual Style

Ray's cinematography in this documentary demonstrates his mastery of visual storytelling even in non-fiction format. The camera moves with a contemplative grace across Tagore's photographs and paintings, allowing viewers to absorb the details. Ray uses slow pans and zooms to create a sense of intimacy with the archival materials. The lighting is carefully controlled to enhance the texture of old photographs and paintings, bringing them to life on screen. Ray incorporates actual footage of Tagore where available, seamlessly blending it with still images and dramatic reconstructions. The cinematography also captures the essence of places significant to Tagore's life - Jorasanko, Santiniketan, and the Bengal landscape that inspired so much of his poetry. Ray's visual approach avoids the static, academic feel common in documentaries of the era, instead creating a fluid, poetic visual narrative that mirrors Tagore's artistic sensibility.

Innovations

Ray's documentary was technically innovative for its time, particularly in its integration of different media forms. The film was one of the first in India to use photo-animation techniques extensively, bringing static photographs to life through careful camera movements. Ray employed sophisticated optical printing techniques to blend archival footage with contemporary shots seamlessly. The documentary also pioneered the use of dramatic reconstruction in Indian documentary filmmaking, creating reenactments of key moments from Tagore's life that were historically accurate yet cinematically compelling. The sound recording and mixing were particularly challenging given the need to integrate Tagore's music, narration, and ambient sounds, but Ray achieved a balanced, clear audio mix. The film's editing, done by Ray himself, demonstrated his ability to create narrative flow even with disparate archival materials. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for documentary filmmaking in India.

Music

The soundtrack of Ray's documentary is a carefully curated selection of Tagore's own musical compositions, known as Rabindra Sangeet. Ray, being a music connoisseur himself, chose pieces that reflected different periods and moods of Tagore's creative life. The music serves not just as background but as a narrative element, illustrating Tagore's evolution as a composer and his philosophical journey. The film features performances by renowned singers of the time, including Debabrata Biswas and Kanika Banerjee, who were considered authorities on Rabindra Sangeet. Ray's own narration, delivered in a measured, thoughtful tone, complements the musical selections. The sound design incorporates ambient sounds from locations significant to Tagore - the rustling of leaves at Santiniketan, the sounds of rural Bengal, and the urban atmosphere of Kolkata. The soundtrack creates an immersive experience that helps viewers connect emotionally with Tagore's world.

Famous Quotes

The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high, into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

I have become my own version of an optimist. If I can't make it through one door, I'll go through another door or I'll make a door.

The butterfly counts not months but moments, and has time enough.

Let your life lightly dance on the edges of Time like dew on the tip of a leaf.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Ray's camera slowly pans across Tagore's childhood photographs while his narration sets the tone for the journey ahead.

- The segment showing Tagore's paintings, with Ray's camera lingering on each work to reveal the artist's evolving style and philosophical depth.

- The reenactment of Tagore receiving the Nobel Prize news, capturing the historic moment with understated dignity.

- The scenes of Santiniketan, showing the educational institution Tagore founded, with students learning in natural surroundings.

- The final sequence where Tagore's voice (from archival recordings) recites his poetry, creating a powerful emotional connection with the audience.

Did You Know?

- This was Satyajit Ray's first documentary film, marking his debut in non-fiction filmmaking after establishing himself as a master of narrative cinema with the Apu Trilogy.

- Ray, who was also a talented writer and musician, had a personal connection to Tagore's work - his father Sukumar Ray was a contemporary and admirer of Tagore.

- The film was commissioned as part of the nationwide centenary celebrations of Tagore's birth in 1861, making it a state-sponsored tribute to the national icon.

- Ray used his own voice for the English narration, lending a personal touch to the documentary that reflected his deep respect for Tagore.

- The documentary features rare photographs of Tagore from various stages of his life, many of which were sourced from private family collections.

- Tagore's own paintings, which he began creating late in life, are prominently featured in the film to illustrate his artistic evolution.

- The musical score incorporates Tagore's own compositions (Rabindra Sangeet), performed by notable artists of the time.

- Ray had to obtain special permissions to film at Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Tagore's ancestral home in Kolkata.

- The documentary was one of the first Indian films to use a combination of archival materials and dramatic reconstruction in documentary storytelling.

- Despite its short runtime of 31 minutes, the film took nearly six months to research and produce due to the extensive archival work involved.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Ray's documentary for its poetic approach and sensitive handling of Tagore's legacy. The Times of India called it 'a fitting tribute to a national icon, rendered with the artistic sensibility we expect from Satyajit Ray.' International critics noted how Ray brought his narrative filmmaking skills to documentary, creating a work that was both informative and emotionally resonant. The film was particularly appreciated for its balanced portrayal of Tagore, avoiding both hagiography and excessive criticism. Over the decades, the documentary has been recognized as a landmark in Indian documentary cinema, with film scholars citing it as an example of how artistic filmmaking can enhance documentary storytelling. Modern critics continue to praise the film's timeless quality and its role in preserving Tagore's legacy for future generations.

What Audiences Thought

The documentary was warmly received by Indian audiences, particularly in Bengal where Tagore remains a cultural icon. Many viewers appreciated Ray's respectful approach to the subject and the film's educational value. The film was screened widely in schools and cultural institutions as part of the centenary celebrations. International audiences, especially those unfamiliar with Tagore's work, found the documentary an accessible introduction to the polymath's life and contributions. The film's relatively short runtime made it suitable for various screening contexts, from cinema halls to educational institutions. Over the years, the documentary has maintained its appeal, with new generations discovering it through film festivals, retrospectives of Ray's work, and digital platforms. Audience members often comment on how the film captures not just Tagore's achievements but his spiritual and philosophical essence.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Award for Best Documentary Film (1961)

- Golden Lotus Award for Best Non-Fiction Film at the National Film Awards

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Robert Flaherty's documentary style

- John Grierson's documentary principles

- European art documentary tradition

- Indian narrative cinema conventions

- Tagore's own writings on art and aesthetics

This Film Influenced

- The World of Apu (documentary elements)

- Inner Eye (Ray's documentary on Benode Behari Mukherjee)

- Sukumar Ray (Ray's documentary on his father)

- Various Indian biographical documentaries of the 1960s-70s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) and is considered part of India's cinematic heritage. Digital restoration work was completed in the early 2000s as part of a broader effort to preserve Satyajit Ray's filmography. The original negatives are stored in climate-controlled facilities at the NFAI in Pune. The film has also been preserved by the Academy Film Archive and the British Film Institute as part of their Satyajit Ray collections. Regular screenings are held at film archives and museums to ensure public access to this important documentary.