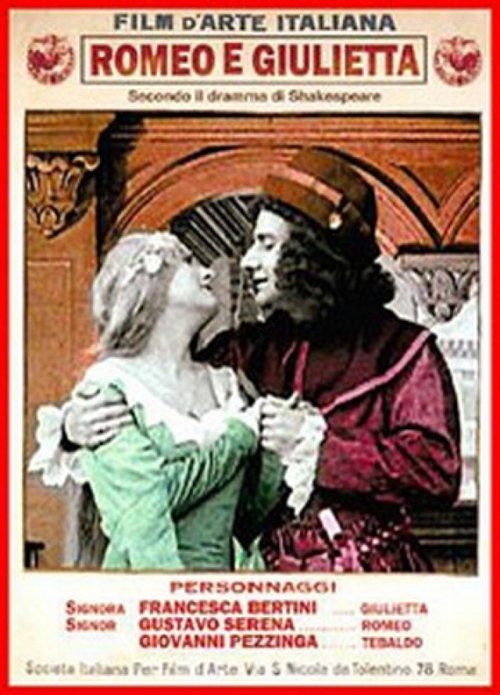

Romeo e Giulietta

"La più grande tragedia d'amore di tutti i tempi"

Plot

This 1912 Italian adaptation follows the tragic romance of Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet in Renaissance Verona. The film chronicles their forbidden love that blossoms despite their families' bitter feud, their secret marriage conducted by Friar Laurence, and the series of tragic misunderstandings that lead to their deaths. After Romeo is banished for killing Tybalt in a duel, Juliet fakes her death with a sleeping potion to avoid an arranged marriage. When Romeo fails to receive the message explaining Juliet's plan, he returns to Verona, finds her seemingly lifeless body in the tomb, and takes his own life with poison. Juliet awakens to find Romeo dead and, in her grief, fatally stabs herself with his dagger, bringing the two feuding families together in shared sorrow.

About the Production

This was one of the earliest feature-length adaptations of Shakespeare's work, produced during the golden age of Italian cinema. The film utilized elaborate sets and costumes to recreate Renaissance Verona, with particular attention to historical accuracy in the architecture and period dress. Director Ugo Falena, who was also a renowned opera director, brought theatrical sensibility to the film's staging and composition. The production employed hundreds of extras for the crowd scenes, particularly the street brawls between the Montagues and Capulets.

Historical Background

This film was produced during what is now considered the golden age of Italian cinema (1910-1916), when Italian films dominated the international market. Italy was a leading film-producing nation, second only to France, and Italian epics and historical dramas were particularly popular worldwide. The year 1912 was significant in cinema history as it marked the transition from short films to feature-length productions. This adaptation of Shakespeare came at a time when filmmakers were beginning to recognize the potential of adapting literary classics for the screen. The film also emerged during a period of cultural renaissance in Italy, with growing national pride and interest in the country's artistic heritage. The production reflected Italy's desire to compete with other European nations in cultural prestige, using cinema as a medium to showcase Italian artistry and technical prowess.

Why This Film Matters

'Romeo e Giulietta' represents a crucial milestone in the history of film adaptations of Shakespeare, demonstrating that complex literary works could be successfully translated to the silent medium. The film helped establish Francesca Bertini as one of cinema's first true international stars, paving the way for future film divas. Its success proved that audiences would embrace serious dramatic content in feature films, encouraging other producers to invest in ambitious literary adaptations. The film's international distribution helped spread Italian cinema's influence globally and contributed to the perception of Italy as a leader in artistic filmmaking. It also established conventions for filming Shakespeare that would influence subsequent adaptations, particularly in its use of visual storytelling to convey complex emotions and relationships without dialogue.

Making Of

The production of 'Romeo e Giulietta' was a major undertaking for Film d'Arte Italiana, one of Italy's most prestigious production companies of the era. Director Ugo Falena brought his extensive opera background to the project, staging scenes with theatrical grandeur while embracing the new medium of cinema. Francesca Bertini, already a major star, was reportedly very involved in the creative process, contributing to costume design and scene staging. The film required extensive location shooting in Rome, where the production team transformed parts of the city to resemble 16th-century Verona. The famous balcony scene was particularly challenging to film, requiring special scaffolding and careful lighting to achieve the romantic atmosphere. The sword fights were performed by professional fencers, and actors trained for weeks to master the choreography. Contemporary accounts suggest that the production was plagued by weather delays during outdoor scenes, but the cast and crew's dedication resulted in what was considered a technical and artistic triumph for its time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Alberto Degli Abbati was considered advanced for its time, utilizing innovative lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and highlights. The film employed location shooting to achieve authentic outdoor scenes, unusual for the period when most filming occurred in studios. The camera work included dynamic movements for the action sequences and carefully composed static shots for dramatic moments. The use of deep focus in certain scenes allowed for complex staging with multiple characters. The film was originally tinted using the Pathécolor process, with different colors used to enhance the emotional tone of specific scenes - blue for night scenes, amber for romantic moments, and red for dramatic confrontations.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations for its time, including the use of multiple camera setups for complex scenes and advanced matte painting techniques for creating the Verona cityscape. The production employed sophisticated special effects for the potion scene, using double exposure techniques to show Juliet's apparent death. The film's editing was particularly advanced for 1912, using cross-cutting to build tension during parallel action sequences. The sword fighting sequences utilized innovative camera angles and editing rhythms to create dynamic action. The production also experimented with location sound recording, though this was primarily for creating reference tracks for the musical accompaniment.

Music

As a silent film, 'Romeo e Giulietta' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The score was typically adapted from classical compositions, including pieces by Tchaikovsky, Berlioz, and Gounod, all of whom had composed music based on Romeo and Juliet. Some theaters commissioned original compositions, while others used compiled scores. The music was crucial for conveying the emotional content of the story and was synchronized with cue sheets provided to theater musicians. The film's romantic and tragic themes were enhanced through carefully selected musical pieces that corresponded to the mood of each scene.

Famous Quotes

These violent delights have violent ends

For never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo

My only love sprung from my only hatred

Parting is such sweet sorrow

Good night, good night! Parting is such sweet sorrow, That I shall say good night till it be morrow

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic balcony scene where Romeo declares his love for Juliet from below her window, filmed with romantic lighting and careful composition

- The sword fight between Romeo and Tybalt, choreographed with authentic Renaissance fencing techniques and dynamic camera work

- The tomb scene where Romeo discovers the seemingly dead Juliet and takes his own life, followed by Juliet's awakening and suicide, filmed in an elaborately constructed crypt set with atmospheric lighting

Did You Know?

- This was the first Italian feature film adaptation of Romeo and Juliet and one of the earliest feature-length Shakespeare films ever made.

- Francesca Bertini, who played Juliet, was one of the first international film stars and was known as 'the Italian diva' of silent cinema.

- Director Ugo Falena was not only a filmmaker but also a respected opera director and composer, which influenced his approach to the dramatic elements of the story.

- The film was released in multiple countries with different titles: 'Romeo and Juliet' in English-speaking countries, 'Roméo et Juliette' in France, and 'Romeo und Julia' in Germany.

- Gustavo Serena, who played Romeo, also directed several films and was a prominent figure in early Italian cinema.

- The film's intertitles were written in the elegant Italian style of the period, often incorporating poetic language that reflected Shakespeare's original verse.

- The sword fight scenes were choreographed with authentic Renaissance fencing techniques, unusual for films of this era.

- The film was shot on 35mm film and was originally tinted in various colors to enhance the emotional impact of different scenes.

- This adaptation was considered quite faithful to Shakespeare's play for its time, including many scenes that were often cut in later versions.

- The tomb scene was filmed in a specially constructed set that was praised by contemporary critics for its atmospheric and realistic appearance.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its artistic ambition and technical achievements. The Italian press hailed it as a triumph of national cinema, with particular acclaim for Francesca Bertini's performance and Ugo Falena's direction. French and British critics noted the film's faithful adaptation of Shakespeare's play and impressive production values. The film's visual beauty and emotional power were frequently mentioned in reviews of the period. Modern film historians consider it an important early example of literary adaptation in cinema, though some note that its acting style appears dated by contemporary standards. The film is now recognized as a significant artifact from the golden age of Italian cinema and an important milestone in the history of Shakespeare on film.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences across Europe and North America, becoming one of the most successful Italian films of 1912. Audiences were particularly drawn to Francesca Bertini's passionate performance as Juliet, which helped establish her as a major star. The tragic love story resonated with viewers of the era, and the film's spectacular sets and action sequences provided the entertainment value expected by cinema audiences of the time. Contemporary accounts describe emotional reactions from audiences, with many reportedly weeping during the final tomb scene. The film's success led to increased demand for Italian films internationally and helped cement the country's reputation for producing high-quality dramatic cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Italian Film Production (1912, Italian Film Critics Association)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Shakespeare's original play 'Romeo and Juliet' (1597)

- Arthur Brooke's 'The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet' (1562)

- Italian opera traditions

- Victorian theatrical adaptations of Shakespeare

This Film Influenced

- Romeo and Juliet (1916)

- Romeo and Juliet (1936)

- West Side Story (1961)

- Romeo + Juliet (1996)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in incomplete form with several reels missing. The surviving footage has been restored by the Cineteca Nazionale in Rome and the British Film Institute. A restored version with reconstructed intertitles exists, but approximately 15-20 minutes of the original footage is believed lost. The surviving elements show significant deterioration but have been digitally preserved. Color-tinted versions exist in some archives, though the original coloring has faded in many prints.