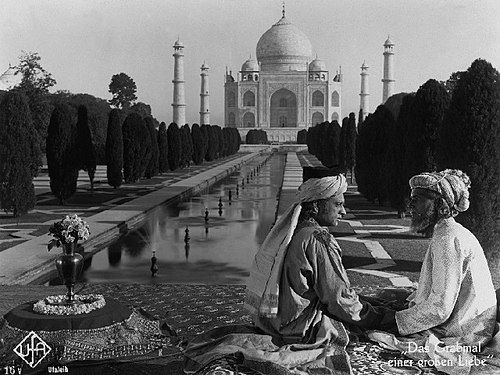

Shiraz: A Romance of India

"The Romance That Built the Taj Mahal"

Plot

Set in 17th century Mughal India, 'Shiraz: A Romance of India' tells the legendary origin story of the Taj Mahal. The film follows Selima, a princess-foundling raised by a humble potter, who shares a deep bond with her adoptive brother Shiraz. When Selima is abducted and sold as a slave to Prince Khurram, the future Emperor Shah Jehan, he falls deeply in love with her beauty and spirit, much to the jealousy of the court dancer Dalia. After Shiraz is caught attempting to rescue Selima, he is condemned to be trampled by an elephant, but a royal pendant reveals Selima's true identity as a princess, saving her brother and allowing her to marry the prince, becoming Empress Mumtaz Mahal. Years later, when Selima dies in 1629, the grief-stricken emperor commissions the magnificent Taj Mahal as her memorial, with the now elderly and blind Shiraz designing the architectural masterpiece that will immortalize their tragic love story.

Director

About the Production

The film was shot entirely on location in India over several months, utilizing authentic Mughal architecture and costumes. The production employed hundreds of local extras and craftsmen to recreate the opulence of the Mughal court. The elephant trampling scene was filmed using careful camera angles and editing techniques to ensure safety while maintaining dramatic impact. The film featured extensive color tinting by hand, a labor-intensive process that added visual richness to key sequences.

Historical Background

The late 1920s was a period of significant transition in world cinema, with silent films reaching their artistic peak just before the advent of sound. 'Shiraz' emerged during the waning years of the British Raj in India, a time when Indian cinema was beginning to develop its own identity while still heavily influenced by Western filmmaking techniques. The film's production coincided with growing Indian nationalist movements, and its emphasis on Indian history and culture can be seen as part of a broader cultural renaissance. The collaboration between German and Indian filmmakers was particularly notable given the political tensions in Europe that would soon lead to World War II. The film also reflected the Western fascination with 'exotic' Eastern cultures that was common in the 1920s, while simultaneously presenting Indian history from an Indian perspective.

Why This Film Matters

'Shiraz: A Romance of India' holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest Indian films to gain international recognition. It demonstrated that Indian stories and aesthetics could appeal to global audiences, paving the way for future Indian cinema exports. The film's portrayal of Mughal history and the Taj Mahal's origin story helped romanticize Indian cultural heritage for international viewers while reinforcing national pride within India. Its success proved the viability of international co-productions in the Indian film industry, a model that would become increasingly important in later decades. The film also represents an important milestone in the representation of Indian culture on screen, avoiding many of the caricatures and stereotypes common in Western productions of the era. Its restoration and preservation by the British Film Institute has ensured that this crucial piece of cinematic history remains accessible to modern audiences and scholars.

Making Of

The making of 'Shiraz' was a remarkable example of early international collaboration in cinema. German director Franz Osten, along with his cinematographer Emil Schünemann, traveled to India to work with Indian producer-actor Himansu Rai. The production faced numerous challenges including extreme weather conditions, communication barriers between the German and Indian crew members, and the logistical complexity of filming at multiple historical sites. The casting process was particularly interesting - Himansu Rai discovered Enakshi Rama Rau while she was performing in a stage play and immediately cast her as Selima. The film's elaborate costumes and sets required months of preparation, with local craftsmen working tirelessly to recreate the splendor of the Mughal era. The production was notably progressive for its time, employing many local Indian technicians and crew members in significant roles, rather than treating them merely as laborers.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Emil Schünemann was groundbreaking for its time, featuring sweeping shots of Indian landscapes and architecture that captured the grandeur of the Mughal Empire. The film made extensive use of natural lighting, particularly in outdoor sequences at historical monuments. Schünemann employed innovative camera techniques including dramatic low angles to emphasize the majesty of the architecture and intimate close-ups to capture the emotional nuances of the performances. The film featured carefully composed tableaus that drew inspiration from Mughal miniature paintings, creating a distinctive visual aesthetic. The use of color tinting added emotional depth to key sequences, with warm amber tones for romantic scenes and cool blue tones for moments of tragedy.

Innovations

The film was technically ambitious for its era, featuring complex location shooting at multiple historical sites across India. The production utilized innovative camera mounting techniques to capture dynamic shots of the Taj Mahal and other monuments. The film's special effects, particularly in the elephant trampling sequence, were achieved through clever editing and camera tricks rather than dangerous stunts. The extensive use of color tinting was a labor-intensive process that required each frame to be hand-colored for certain sequences. The film also featured elaborate makeup and prosthetics to age characters convincingly over the span of several decades in the story.

Music

As a silent film, 'Shiraz' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The score typically combined Western classical music with traditional Indian instruments and melodies, reflecting the film's cross-cultural nature. Some theaters employed full orchestras while others used smaller ensembles or even single pianists. The musical accompaniment was carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with specific musical motifs associated with different characters and emotional states. In recent years, new musical scores have been composed for the restored version, including a notable score by the British group Muse Quality that blends Indian and Western musical traditions.

Famous Quotes

Love builds monuments that time cannot destroy

In blindness, I see more clearly the beauty I once could only glimpse

The Taj will stand as eternal witness to a love that death itself could not end

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic elephant trampling sequence where Shiraz is saved at the last moment

- The reveal of Selima's royal identity through the pendant

- The final scene showing the elderly, blind Shiraz designing the Taj Mahal from memory

- The lavish court dance sequence featuring authentic Indian classical dance

- The emotional farewell between Selima and her adoptive family

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest international co-productions between Britain and India, setting a precedent for cross-cultural filmmaking

- Director Franz Osten was a German filmmaker who made several films in India during the 1920s as part of a unique collaboration with Indian producer Himansu Rai

- The film's star Himansu Rai was not only the lead actor but also the producer and driving force behind the Indo-German film partnership

- The Taj Mahal sequences were filmed at the actual monument, with special permission from British authorities

- The film was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the British Film Institute archives

- Enakshi Rama Rau, who played Selima, was discovered by Himansu Rai and this was her film debut

- The film featured authentic Indian classical dance sequences performed by professional dancers from the region

- The production used actual Indian artisans to create the period costumes and props, ensuring historical accuracy

- The film was released in both silent and synchronized sound versions for different markets

- The elephant used in the film was a trained performing elephant named Moti, who was specially hired from a royal stable

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Shiraz' for its visual splendor, authentic settings, and powerful performances. The Times of London described it as 'a magnificent spectacle that brings the glory of Mughal India to life with unprecedented authenticity.' German critics particularly appreciated the film's artistic cinematography and the successful fusion of Eastern storytelling with Western cinematic techniques. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as an important work of early transnational cinema, with many noting its sophisticated visual language and its role in establishing conventions for historical epics in Indian cinema. The British Film Institute's restoration has allowed contemporary reviewers to appreciate the film's technical achievements and its place in film history.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences both in India and internationally, particularly in Britain and Germany where it enjoyed successful theatrical runs. Indian audiences appreciated the film's celebration of their cultural heritage and the dignified portrayal of their history. Western audiences were captivated by the film's exotic settings and lavish production values. The film's romantic storyline and spectacular visuals transcended cultural barriers, making it accessible to diverse audiences. Despite being a silent film, its emotional power and visual storytelling resonated strongly with viewers of the era. The film's success helped establish a market for Indian films internationally and encouraged further cross-cultural collaborations.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for silent films in 1928, but it received critical acclaim at international film festivals

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Mughal miniature paintings

- Indian classical dance traditions

- Historical epics of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Mughal-e-Azam (1960)

- Taj Mahal (1963)

- Jodhaa Akbar (2008)

- Bajirao Mastani (2015)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for decades but a complete 35mm print was discovered and preserved by the British Film Institute. The BFI undertook a major restoration project in the early 2000s, which included digital restoration of damaged footage and reconstruction of missing intertitles from surviving scripts. The restored version premiered at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival and has since been screened at film festivals worldwide. The restored film is now part of the BFI National Archive and is considered one of the best-preserved examples of early Indian cinema.