Something Good — Negro Kiss

Plot

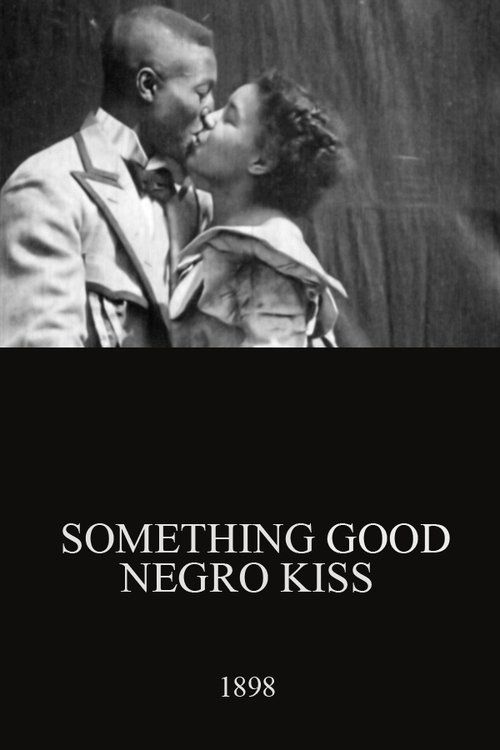

This groundbreaking short film depicts African American performers Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown engaged in a tender romantic encounter. The couple shares affectionate moments including holding hands, embracing, and sharing multiple kisses on the lips - a remarkably intimate portrayal for the era. The film captures their natural chemistry and genuine affection, presenting their relationship with dignity and warmth. Unlike the caricatured depictions common in the period, this film portrays African Americans as loving, sophisticated individuals engaged in normal romantic behavior. The brief but powerful scene concludes with the couple continuing their affectionate display, creating a lasting image of Black love and intimacy.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in a single take using early motion picture equipment, likely an Edison Kinetoscope or similar camera. The film was probably shot in Selig's Chicago studio or on a simple indoor set. The production required minimal setup given its short length and simple concept. Both performers were likely vaudeville actors recruited for this experimental film. The spontaneous and natural quality of their interaction suggests they may have been encouraged to improvise their affectionate display rather than follow strict choreography.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1898, during the earliest days of cinema and at the height of the Jim Crow era in America. This was a period of severe racial segregation and widespread discrimination against African Americans. The Spanish-American War was raging, and the United States was emerging as an imperial power. In cinema, this was the nickelodeon era, with films typically lasting less than a minute and shown in penny arcades or traveling exhibitions. Most depictions of African Americans in media at the time were through minstrel shows and racist caricatures. The fact that this film presented Black people as sophisticated, loving individuals engaged in normal romantic behavior was revolutionary. The film emerged just three years after the first public film exhibition in America and represents one of the earliest examples of cinema being used to challenge social norms rather than reinforce them.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a groundbreaking moment in cinematic history as the earliest known depiction of African American intimacy on screen. Its significance lies not only in its age but in its revolutionary portrayal of Black love and affection during an era when such representations were virtually nonexistent. The film challenges the racist stereotypes and caricatures that dominated American media in the late 19th century. Its rediscovery in 2017 forced film historians to reconsider the narrative of early cinema's treatment of African Americans. The film serves as powerful evidence that positive representations of Black life existed even in cinema's infancy, contrary to the assumption that early films uniformly depicted African Americans through racist caricatures. It has become an important cultural artifact for discussions about representation in media and the history of African American cinema.

Making Of

The film was created by William Nicholas Selig, a pioneer of American cinema who established one of the first motion picture production companies in Chicago. Selig, unlike many of his contemporaries, occasionally featured African American performers in his films without resorting to the caricatured minstrel show stereotypes that dominated the era. The production was remarkably simple by modern standards - requiring only a camera, basic lighting, and the two performers. The intimate nature of the content was revolutionary for 1898, when even white couples rarely showed such affection on screen. The film was likely shot in one take, with the performers instructed simply to display affection naturally. Both Suttle and Brown were probably recruited from Chicago's vaudeville scene, where interracial performances were more common than in other American cities.

Visual Style

The cinematography is typical of films from 1898, using a single stationary camera positioned to capture the full action. The black and white imagery shows the technical limitations of early film equipment, with some flickering and exposure variations. Despite these technical constraints, the framing effectively captures the intimacy of the moment. The camera work is straightforward but effective, allowing the focus to remain on the performers' natural interaction. The lighting appears to be basic studio lighting, creating clear visibility of the subjects. The composition places the couple centrally in the frame, emphasizing their connection. While technically primitive by modern standards, the cinematography serves its purpose well, creating a window into a tender moment that transcends its technical limitations.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in terms of cinematography or editing, the film's achievement lies in its social and cultural breakthrough rather than technical innovation. The film uses standard 35mm film stock and typical camera equipment for the period. Its technical significance comes from its preservation and restoration, which have allowed modern audiences to view this important historical artifact. The restoration process involved cleaning and digitizing the original film elements to ensure their survival for future generations. The film's existence and survival represent an achievement in itself, given how many early films have been lost to time. The simple, direct approach to filming - one continuous take with no cuts - was typical of the era but proves effective in capturing the authentic moment of affection between the performers.

Music

The original film was silent, as all films were in 1898. No original musical score was composed specifically for this short piece. In contemporary exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate music of the period. Modern presentations of the film often feature period-appropriate music or specially commissioned scores that enhance the emotional impact of the scenes. Some screenings have used romantic piano music from the 1890s, while others have employed contemporary African American spirituals or ragtime pieces to provide cultural context. The absence of synchronized sound actually serves to emphasize the visual storytelling and the universal language of affection that the film portrays.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue exists as this is a silent film, but the visual narrative speaks volumes about love transcending racial barriers in an era of segregation

Memorable Scenes

- The entire 29-second film consists of one memorable scene: Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown sharing tender kisses and embraces, their genuine affection creating a powerful image of Black love that was revolutionary for its time and remains moving today

Did You Know?

- This is the earliest known surviving film depicting African American intimacy and affection on screen

- The film was lost for over a century before being rediscovered and identified in 2017 by film scholars at the University of Chicago

- It predates D.W. Griffith's controversial 'The Birth of a Nation' by 17 years, offering a stark contrast to typical racist portrayals of the era

- The film was produced during the Jim Crow era, making its positive representation of African Americans particularly revolutionary

- Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown were actual vaudeville performers, not professional actors

- The film was likely intended for exhibition on nickelodeons and peep show devices rather than theatrical projection

- The original film title 'Something Good' was later expanded to 'Something Good — Negro Kiss' by archivists for descriptive purposes

- The film runs at approximately 16 frames per second, standard for silent films of the period

- It was added to the National Film Registry in 2022 for its cultural and historical significance

- The couple's natural chemistry suggests they may have been romantically involved in real life

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception from 1898 is impossible to determine as film criticism was in its infancy and few records exist from that period. Modern critics and scholars, however, have universally praised the film's historical importance and emotional power. Upon its rediscovery, film historians hailed it as a revelation that challenges assumptions about early cinema's racial politics. Critics have noted the remarkable naturalness and chemistry between the performers, contrasting it with the staged quality of most films from the era. The film has been celebrated for its warmth, dignity, and the genuine affection it portrays. Modern reviewers have described it as 'heartwarming,' 'revolutionary,' and 'a treasure of cinematic history.' The film's inclusion in the National Film Registry reflects its critical recognition as a work of enduring cultural and historical significance.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception from 1898 is not documented, as systematic audience research did not exist in early cinema. However, the fact that the film was produced and distributed suggests there was some market for such content, at least in certain venues. Modern audiences who have discovered the film through screenings and online distribution have responded with overwhelming positivity. Many viewers express surprise and emotion at seeing such a natural, tender depiction of Black romance from the 19th century. The film often elicits strong emotional responses, particularly from African American viewers who rarely see such historical representations of Black love. Contemporary audiences frequently comment on the couple's chemistry and the film's unexpected tenderness. The film has become popular in film studies courses and at special screenings, where it consistently moves audiences with its simple but powerful message of love and dignity.

Awards & Recognition

- Added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (2022)

- Honored by the Academy Film Archive for preservation and restoration

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early French actuality films

- Edison Manufacturing Company productions

- Vaudeville performance traditions

This Film Influenced

- Early African American cinema

- Race films of the 1920s-1940s

- Contemporary discussions of representation in media

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for over a century before its rediscovery in 2017. It has since been preserved by the Library of Congress and added to the National Film Registry in 2022. The original film elements have been digitized and restored, ensuring the survival of this important historical artifact. The restoration work was undertaken by film preservation specialists who cleaned and stabilized the deteriorating film stock. The preserved version is now available through the Library of Congress and various archival institutions. The film's preservation represents a significant victory for cinema history, as it ensures that this groundbreaking representation of African American intimacy will remain accessible to future generations.