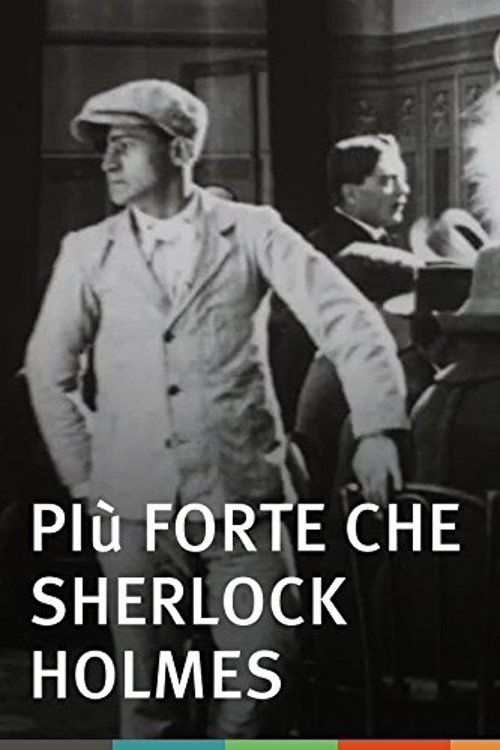

Stronger than Sherlock Holmes

Plot

A bourgeois gentleman becomes engrossed reading newspaper stories about police pursuits and criminal escapades, enthusiastically commenting on the thrilling accounts to his increasingly bored wife. Eventually, his wife drifts off to sleep from his monotonous commentary, and soon after, lulled by the cozy warmth of the living room, the gentleman himself falls into slumber. In a fantastical sequence, the shadow of an escaping robber literally springs to life from the pages of the newspaper, transforming the mundane setting into a dream world of crime and pursuit. The sleeping man awakens to find himself miraculously dressed in a police uniform, compelled to chase the phantom criminal through a surreal landscape where the boundaries between reality and fantasy blur. The dream chase culminates in a comical confrontation between the amateur detective and the newspaper-born criminal, ultimately resolving with the gentleman's abrupt awakening back to his mundane domestic reality.

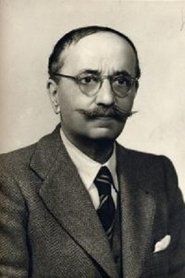

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema, when Turin served as a major production hub. Itala Film, under Giovanni Pastrone's leadership, was one of Italy's most innovative studios, pioneering techniques that would influence cinema worldwide. The film utilized early special effects to create the illusion of the robber's shadow coming to life from the newspaper, demonstrating the studio's technical capabilities. The production likely employed the studio's elaborate indoor sets, which were among the most sophisticated in Europe at the time.

Historical Background

The year 1913 marked the height of the silent film era and the peak of Italian cinema's international influence. Italy was experiencing a cultural renaissance, with cinema playing a crucial role in establishing the country's cultural identity on the world stage. The film industry in Turin, where Itala Film was based, was booming, with studios producing hundreds of films annually for global distribution. This period saw the development of many cinematic techniques that would become standard in filmmaking, including more sophisticated editing, camera movement, and special effects. The popularity of detective stories, particularly Sherlock Holmes, reflected broader societal interests in rationality, science, and order during an era of rapid technological and social change. The film's comedic take on the detective genre also speaks to the growing sophistication of film audiences, who appreciated both parody and original storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' represents an important example of early Italian comedy and the country's contribution to the development of cinematic language. The film demonstrates how Italian filmmakers were not only producing grand historical epics but also exploring more intimate, domestic comedies that reflected contemporary life. Its dream sequence theme and meta-narrative elements (a story within a story about storytelling itself) show early experimentation with film form that would influence later surrealist and fantasy cinema. The film also illustrates the international nature of early cinema, with an Italian production engaging with a British cultural icon (Sherlock Holmes), demonstrating how quickly film became a global medium. As part of Itala Film's diverse output, it shows how major studios of the era balanced commercial entertainment with artistic innovation, creating works that both entertained audiences and pushed the boundaries of what cinema could achieve.

Making Of

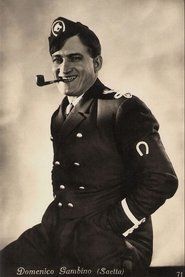

The production of 'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' took place at Itala Film's state-of-the-art studios in Turin, which were among the most advanced film facilities in Europe at the time. Giovanni Pastrone, as both director and studio head, brought his technical expertise to this comedy, employing innovative camera techniques and special effects to create the fantastical dream sequences. The newspaper coming to life effect was achieved through careful manipulation of shadows and lighting, a technique that required precise timing and coordination between the cinematographer and performers. The cast, led by Domenico Gambino and Emilio Vardannes, worked within the constraints of silent film acting, using exaggerated gestures and facial expressions to convey the comedic elements of the story. The production team likely created multiple versions of the film for international distribution, as was common practice for Italian films of this era, with different intertitles translated for various markets.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' employed the techniques and visual style typical of Italian cinema in 1913, while also incorporating innovative elements for the dream sequences. The film likely utilized the sophisticated lighting equipment available at Itala Film's studios to create the dramatic shadows necessary for the robber's shadow to come to life. Camera work would have been relatively static by modern standards, but may have included some movement typical of Pastrone's more ambitious productions. The visual contrast between the mundane domestic setting and the fantastical dream world would have been achieved through careful set design and lighting. The black and white photography of the era would have emphasized the play of light and shadow crucial to the film's central conceit.

Innovations

The film's most notable technical achievement was the special effect of the robber's shadow coming to life from the newspaper, which required careful manipulation of lighting, shadows, and possibly multiple exposure techniques. This demonstrated the growing sophistication of visual effects in early cinema. The seamless transition from reality to dream state represented an early exploration of psychological storytelling techniques in film. The production likely benefited from Itala Film's advanced studio facilities and equipment, which were among the best in Europe at the time. The film's editing, particularly in the chase sequences, would have employed the increasingly sophisticated techniques being developed in Italian cinema during this period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical screenings. The specific musical score is not documented, but typical accompaniment for Italian comedies of this era would have included popular classical pieces, operatic excerpts, and original compositions performed by a theater's house orchestra or pianist. The music would have been synchronized to enhance the comedic timing, dramatic moments, and particularly the fantastical dream sequences. The score likely varied between different theaters and showings, as was common practice before standardization of film music in the late 1920s.

Memorable Scenes

- The magical sequence where the robber's shadow literally emerges from the newspaper pages, transforming the static print into a living, moving entity that initiates the dream narrative.

Did You Know?

- The film's Italian title was 'Più forte di Sherlock Holmes', reflecting the international popularity of Arthur Conan Doyle's detective character during this period.

- Giovanni Pastrone, also known by the pseudonym Piero Fosco, was one of the most important figures in early Italian cinema, pioneering techniques like the moving camera.

- The film was released during the peak of Italian film production, when the country was second only to France in cinematic output.

- Itala Film, the production company, was famous for epic historical films like 'Cabiria' (1914), making this comedy a departure from their typical grand-scale productions.

- The film's dream sequence theme was relatively innovative for 1913, predating many famous surrealist films by decades.

- Sherlock Holmes was extremely popular in early cinema, with numerous adaptations and parodies produced across Europe and America.

- The film's short runtime was typical of the period, when most films were one-reel productions lasting 10-15 minutes.

- Domenico Gambino, who played the gentleman, would later become a prominent figure in Italian cinema during the silent era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' is difficult to trace due to the limited documentation of film reviews from this period. However, the film's production by the prestigious Itala Film studio under Giovanni Pastrone's direction suggests it was likely well-received by audiences and critics familiar with the studio's reputation for quality. Modern film historians and archivists recognize the film as an interesting example of early Italian comedy and technical innovation, particularly in its use of dream sequences and special effects. The film is occasionally referenced in studies of early cinema and the work of Giovanni Pastrone, though it remains less studied than his more famous epics like 'Cabiria'.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1913 likely responded positively to the film's clever premise and comedic elements, particularly the fantastical dream sequence that demonstrated cinema's unique ability to bring impossible scenarios to life. The parody of the popular Sherlock Holmes character would have resonated with contemporary viewers familiar with detective stories through both literature and earlier film adaptations. The domestic setting and relatable characters probably made the film accessible to a broad audience, while the technical effects would have impressed viewers with the magical possibilities of the new medium of cinema. As part of Itala Film's diverse slate of productions, the film likely contributed to the studio's reputation for delivering entertaining and technically accomplished films to international audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle

- Early French comedies

- Italian theatrical traditions

- Contemporary newspaper culture

This Film Influenced

- Later surrealist films with dream sequences

- Italian comedy films of the 1920s

- Early fantasy cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Stronger than Sherlock Holmes' is uncertain, as many films from this early period have been lost or exist only in fragmentary form. Some sources suggest that copies may exist in film archives, particularly in Italy, but the film is not widely available for viewing. The survival rate of Italian films from 1913 is estimated to be quite low, with many productions lost due to the nitrate film's instability and lack of systematic preservation efforts in the early 20th century.