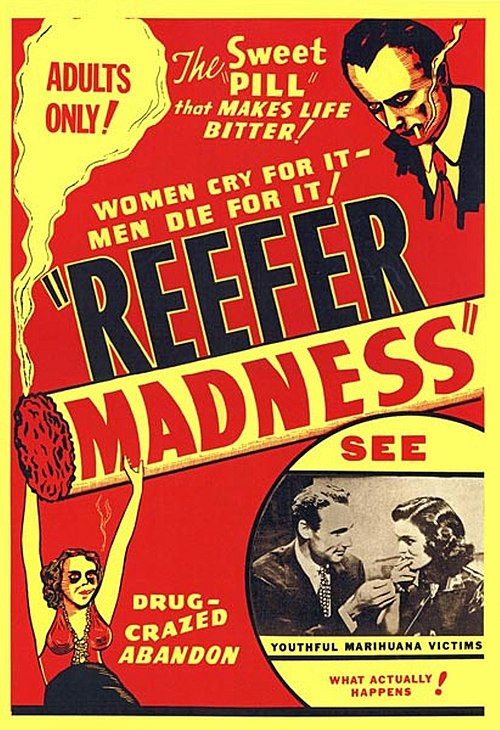

Tell Your Children

"The Burning Question of the Day: Is Your Daughter Safe From This Menace?"

Plot

High school principal Dr. Alfred Carroll delivers a stern warning to parents about the dangers of marijuana, using the tragic story of several teenagers as a cautionary tale. The narrative follows Mary Lane and her brother Jimmy, along with Mary's boyfriend Bill, who are lured into a 'reefer house' by drug dealer Mae Coleman and her partner Jack. As the teenagers begin smoking marijuana, their lives spiral downward - Bill becomes increasingly violent and paranoid, Jimmy gets involved in a hit-and-run accident while high, and Mary is sexually assaulted after being drugged. The film culminates in a series of tragic events including Bill's suicide, Jimmy's arrest, and Mary's mental breakdown, all attributed to their marijuana use. Dr. Carroll concludes by urging parents to protect their children from this 'violent narcotic' that threatens American youth.

About the Production

Originally conceived as a morality tale financed by a church group, the film was later purchased by exploitation film producer Dwain Esper who added sensationalized scenes and re-edited it for broader distribution. The production used inexpensive sets and non-union actors to keep costs low. Many scenes were shot in a single take due to budget constraints, and the film was completed in just three weeks. The notorious 'freak-out' sequences were achieved through exaggerated acting and rapid editing rather than special effects.

Historical Background

The film emerged during the height of the Great Depression when America was experiencing significant social anxiety and moral panic. The 1930s saw the rise of Harry Anslinger's Federal Bureau of Narcotics, which was actively campaigning against marijuana use through propaganda. The film was released just one year before the passage of the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, which effectively criminalized cannabis nationwide. This period also marked the golden age of exploitation films, which used controversial topics to attract audiences while claiming educational value. The film's production coincided with growing concerns about youth delinquency and changing social mores, making its message particularly resonant with conservative audiences of the era.

Why This Film Matters

Despite its initial failure, 'Tell Your Children' (later 'Reefer Madness') has become one of the most culturally significant exploitation films ever made. It represents a perfect example of how propaganda can inadvertently become comedy through exaggeration and the passage of time. The film's rediscovery in the 1970s coincided with the counterculture movement, which embraced it ironically as a symbol of government misinformation about drugs. It has spawned numerous parodies, including a 2005 off-Broadway musical adaptation and a 2005 television movie parody. The film's title 'Reefer Madness' has entered the popular lexicon as a shorthand for exaggerated drug warnings and government propaganda. It remains a staple of midnight movie screenings and is frequently referenced in discussions about drug policy and media manipulation.

Making Of

The film was originally commissioned by a moral organization concerned about drug use among youth, with the intention of creating a serious educational piece. After initial poor reception, exploitation film pioneer Dwain Esper acquired the rights and re-edited the footage to emphasize sensational elements, adding more dramatic scenes and exaggerating the drug effects. The production was notoriously low-budget, with many scenes shot in borrowed locations and props. Director Louis J. Gasnier, who had previously directed major silent films, was reportedly embarrassed by the project but needed work during the Depression. The cast was largely composed of unknown actors who were paid minimal wages, with some reports suggesting they were paid in marijuana during later reshoots. The film's most memorable sequences, including the 'freak-out' scenes, were achieved through creative editing and exaggerated performances rather than sophisticated special effects.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, handled by G. W. 'Bill' Steiner, was typical of low-budget productions of the era but featured some surprisingly effective techniques. The use of Dutch angles and distorted camera movements during the 'marijuana madness' sequences created a sense of disorientation that, while crude, effectively conveyed the intended hysteria. The lighting was harsh and high-contrast, particularly in the reefer house scenes, creating a noir-like atmosphere that was ahead of its time. The film employed rapid editing during the drug sequences, with jump cuts and mismatched shots that contributed to its chaotic feel. Despite budget limitations, the cinematography managed to create memorable visual motifs, particularly the recurring close-ups of bloodshot eyes and sweaty faces during the drug scenes.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, the film did employ some interesting techniques given its budgetary constraints. The use of undercranking during the 'freak-out' sequences created a sped-up effect that, while crude, was effective for its intended purpose. The film's editing, particularly during the marijuana-induced madness scenes, featured rapid cuts and jump cuts that were relatively experimental for the time. The production also made creative use of lighting and camera angles to suggest drug-induced paranoia, including distorted wide-angle lenses and disorienting camera movements. Despite these attempts at technical innovation, the film's most significant technical achievement was its very existence - the fact that such an ambitious (if misguided) production was completed on such a minimal budget.

Music

The film's soundtrack consisted primarily of stock music and public domain compositions, a common practice for low-budget productions of the era. The most notable musical sequence occurs during the piano playing scene, where an accelerated jazz score accompanies the supposedly marijuana-fueled performance. The film also features several diegetic music moments, including a jazz band playing in the reefer house and a melancholic piano piece during Mary's downfall. The sound design was primitive even for 1936, with obvious use of post-dubbing and mismatched audio levels. The musical choices, while unremarkable technically, inadvertently enhanced the film's unintentional comedy, particularly during scenes meant to be serious but accompanied by inappropriate or overly dramatic music.

Famous Quotes

"Marijuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind." - Dr. Alfred Carroll

"The fatal marijuana cigarette may be recognized by the peculiar, pungent odor." - Dr. Alfred Carroll

"You're playing with fire! Where do you get your stuff?" - Bill Harper

"I've been smoking marijuana for five years... and it hasn't hurt me yet!" - Mae Coleman

"There's nothing wrong with marijuana. It's just a gentle relaxant." - Ralph Wiley

"Your daughter may be smoking marijuana right now... and you don't even know it!" - Dr. Alfred Carroll

"The first puff is the beginning of the end!" - Dr. Alfred Carroll

"I feel funny... like I'm floating on air." - Mary Lane

Memorable Scenes

- The infamous piano playing sequence where the musician's hands move impossibly fast while smoking marijuana, achieved through undercranking the camera and creating a surreal, unintentionally hilarious effect that has become the film's most iconic moment.

- The 'reefer madness' sequence where Bill experiences a paranoid hallucination, featuring distorted camera angles, rapid editing, and over-the-top acting that perfectly encapsulates the film's hysterical approach to drug effects.

- The opening scene where Dr. Alfred Carroll addresses the PTA meeting, setting up the film's framing device and delivering its most memorable anti-marijuana propaganda with deadpan seriousness.

- The tragic hit-and-run accident scene where Jimmy, high on marijuana, strikes a pedestrian while driving, representing the film's most dramatic and morally heavy-handed moment.

- The final courtroom scene where Dr. Carroll delivers his closing sermon against marijuana, culminating in the film's most quotable and propagandistic warnings about the 'demon weed'.

Did You Know?

- The film was originally titled 'Tell Your Children' and was intended as a serious educational film funded by a church group

- Producer Dwain Esper purchased the film for $1,000 and added sensationalized content to make it more profitable

- The film was rediscovered in the 1970s and rebranded as 'Reefer Madness,' becoming a midnight movie cult classic

- None of the actors in the film had significant careers afterward, with most appearing in only a few films

- The film was shown to Congress as evidence of marijuana's dangers during the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act hearings

- The infamous piano scene where the player's hands move impossibly fast was achieved through undercranking the camera

- The film's depiction of marijuana effects was completely fabricated, with no scientific basis

- It was considered a 'lost film' for decades until a print was discovered in the 1970s

- The film has been parodied numerous times, including in musical adaptations and comedy sketches

- Despite its anti-drug message, the film became associated with pro-marijuana counterculture in the 1970s

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, the film was largely ignored by mainstream critics, who dismissed it as cheap exploitation fare. The few reviews that appeared condemned it as hysterical propaganda with no artistic merit. In the decades following its rediscovery, critics have reevaluated the film as an unintentional comedy and a fascinating artifact of American cultural history. Modern critics universally praise it as a 'so bad it's good' masterpiece, with its overwrought performances, ridiculous dialogue, and absurd depictions of drug effects providing endless entertainment. The film is now studied in film schools as an example of exploitation cinema and propaganda techniques, with many noting how its failures make it more compelling than many intentionally successful films of its era.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was poor, with the film failing to find an audience in its limited theatrical run. Many viewers found it too preachy and melodramatic, even for 1930s standards. However, following its 1970s rediscovery and rebranding as 'Reefer Madness,' the film developed a massive cult following. Audiences embraced its unintentional humor, with midnight movie screenings becoming interactive events where viewers would shout at the screen and smoke marijuana in defiance of the film's message. The film's cult status has only grown over the decades, with new generations discovering it through home video and streaming platforms. Modern audiences primarily view it as comedy, with many considering it an essential part of cannabis culture and a must-see example of 'so bad it's good' cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- 'The Road to Ruin' (1934) - similar exploitation film format

- Government anti-drug propaganda campaigns of the 1930s

- Temperance movement films from the Prohibition era

- Sensationalist newspaper reports about marijuana

- Harry Anslinger's anti-marijuana crusade

- Earlier morality plays and cautionary tales

This Film Influenced

- 'The Brain That Wouldn't Die' (1962) - similar exploitation aesthetic

- 'Pink Flamingos' (1972) - embraced transgressive exploitation style

- 'The Toxic Avenger' (1984) - 'so bad it's good' approach

- 'Grindhouse' (2007) - deliberate homage to exploitation films

- 'The Disaster Artist' (2017) - celebration of 'so bad it's good' cinema

- Countless modern stoner comedies that reference it ironically

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed to be lost for decades until a 16mm print was discovered in the 1970s. Multiple versions exist due to the film's various re-releases under different titles. The most complete version was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive in the 1990s. The film has since been preserved by several archives including the Library of Congress and is available in high-quality digital transfers. Various versions with different running times and slightly different content exist due to the film's exploitation film history of being re-edited for different markets.