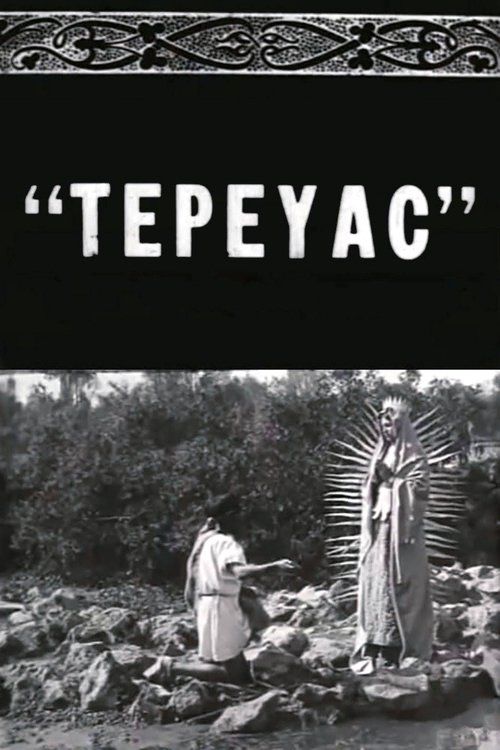

Tepeyac

Plot

Roberto (Roberto Arroyo Carrillo), a young Mexican man, is sent to Europe on a diplomatic mission during World War I. His ship is torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine, leaving his beloved Lupita (Pilar Cota) in Mexico to receive devastating news via telegram. Heartbroken, Lupita seeks solace in her faith, turning to La Virgen de Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexican Catholics. After reading a book detailing the legend of the Virgin's appearance to Juan Diego on Tepeyac Hill, Lupita falls asleep while praying fervently for Roberto's safety. The following morning brings miraculous news - Roberto has survived the attack and is returning home safely. The reunited couple makes a pilgrimage to La Villa del Tepeyac, the church dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe, to give thanks for what they believe is a divine miracle that saved Roberto's life.

About the Production

Filmed during the Mexican Revolution, making production challenging and dangerous. The film was shot on location at the actual Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which was unusual for the time. Director Carlos E. González used actual church interiors and exteriors to authenticate the religious setting. The production faced difficulties due to the political instability in Mexico during 1917, with the film industry still recovering from revolutionary conflicts.

Historical Background

Tepeyac was produced in 1917, a pivotal year in Mexican history. The country was emerging from the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), one of the most significant social upheavals of the 20th century. This same year, Mexico adopted its current Constitution, which would shape the nation for decades to come. The film industry was in its infancy, with most films being short documentaries or simple narratives. Tepeyac represented a bold step toward creating a national cinema that could reflect Mexican identity and values. The film's focus on the Virgin of Guadalupe was particularly significant, as this religious symbol had become increasingly important as a unifying element of Mexican culture during and after the Revolution. The timing of the film's release, during World War I, also influenced its themes of international conflict and the vulnerability of Mexicans abroad.

Why This Film Matters

Tepeyac holds immense cultural significance as one of the foundational texts of Mexican cinema. It established several important precedents: it was among the first Mexican films to successfully blend national identity, religious faith, and contemporary themes. The film's portrayal of the Virgin of Guadalupe helped solidify her image in popular culture and cinema, influencing countless later Mexican films. Its narrative structure - combining modern drama with religious miracle - became a template for many subsequent Mexican films dealing with faith and national identity. The film also demonstrated that Mexican cinema could address sophisticated themes while maintaining broad popular appeal. Its preservation and study have become important for understanding the development of Mexican national cinema and the country's cultural self-perception during the revolutionary period.

Making Of

The making of Tepeyac occurred during one of Mexico's most turbulent historical periods. Director Carlos E. González, a pioneer of Mexican cinema, had to navigate the challenges of filming during the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. The production team faced daily threats from ongoing military conflicts in the region. The casting of Roberto Arroyo Carrillo and Pilar Cota created one of the first romantic pairings in Mexican cinema that would become archetypal. The film's religious sequences were filmed with the cooperation of church authorities, who initially hesitated but eventually supported the project due to its respectful portrayal of Catholic themes. The submarine attack sequence was created using miniature models and clever editing techniques, as actual underwater filming was impossible at the time. The production company, Azteca Film, invested heavily in the project, believing it could establish Mexican cinema's international reputation.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Tepeyac, while limited by the technology of 1917, showed remarkable ambition and artistry. Director Carlos E. González, who also served as cinematographer, employed location shooting at the actual Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, providing authentic visual grounding for the religious narrative. The film used natural lighting for exterior scenes, particularly effective in the sequences shot at Tepeyac Hill. The submarine attack sequence utilized innovative special effects techniques for the time, including miniatures and multiple exposure photography. The film's visual language incorporated both documentary-style realism in the location shots and more stylized compositions for the religious sequences. The cinematography emphasized the contrast between modern Europe (represented through the ship sequences) and traditional Mexico (shown through the church and home scenes). While the surviving fragments show the technical limitations of the era, they also reveal a sophisticated visual approach to storytelling.

Innovations

Tepeyac demonstrated several technical achievements for Mexican cinema of its era. The film's use of location shooting at actual religious sites was innovative, as many contemporary films used studio sets. The submarine attack sequence showcased advanced special effects techniques for Mexican cinema, including model work and editing tricks to simulate the ship's destruction. The film employed cross-cutting between parallel storylines (Roberto's ordeal and Lupita's prayers), a sophisticated narrative technique for the time. The production managed to create convincing European settings despite being filmed entirely in Mexico. The film's length, approximately 70 minutes, was ambitious for Mexican cinema, which primarily produced shorter films. The successful integration of documentary-style location footage with dramatic narrative elements represented an important technical achievement. While the film's technical quality cannot be fully assessed due to the fragmentary nature of surviving prints, contemporary accounts praised its visual sophistication.

Music

As a silent film, Tepeyac would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical runs. The typical score would have included popular Mexican songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed music for key scenes. Religious sequences would likely have been accompanied by traditional Mexican Catholic hymns and organ music. The dramatic moments, such as the submarine attack and the telegram scene, would have been enhanced with tense, rhythmic musical accompaniment. The final pilgrimage scene would have featured celebratory, uplifting music. While no specific composer for the original score is documented, theaters often employed local musicians who would improvise or adapt existing pieces to match the on-screen action. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in conveying the emotional tone of the story, particularly in the religious sequences where the music helped create an atmosphere of reverence and miracle.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, Tepeyac contained no spoken dialogue, but intertitles conveyed key messages including: 'O Virgen Santa, escucha mi ruego' (O Holy Virgin, hear my prayer) and 'Milagro del Señor' (Miracle of the Lord)

Memorable Scenes

- The submarine attack sequence, which used innovative special effects to show the ship's destruction; Lupita's prayer scene at the altar of the Virgin of Guadalupe, where she falls asleep while praying; The dream sequence where the Virgin appears; The emotional reunion of Roberto and Lupita; The final pilgrimage to Tepeyac Hill where the couple gives thanks

Did You Know?

- Tepeyac is considered one of the first full-length feature films produced in Mexico

- The film was produced during the same year as Mexico's current Constitution was adopted (1917)

- Only fragments of the original film survive today, with portions preserved in Mexican film archives

- Director Carlos E. González was also a cinematographer and handled many of the camera shots himself

- The film's focus on the Virgin of Guadalupe reflected the growing importance of Mexican national identity

- Pilar Cota was one of the first major female stars of Mexican cinema

- The film's production coincided with Mexico's entry into the international film market

- Tepeyac was among the first Mexican films to incorporate religious themes as central to its narrative

- The submarine attack sequence was particularly ambitious for its time, requiring special effects that were innovative for Mexican cinema

- The film was initially banned in some conservative Mexican states for depicting modern themes alongside religious content

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Tepeyac was largely positive, with Mexican newspapers of the era praising it as a triumph of national cinema. Critics particularly noted its ambitious scope and respectful treatment of religious themes. The film was hailed as evidence that Mexican filmmakers could compete with foreign productions. Modern film historians and critics have come to regard Tepeyac as a seminal work of early Mexican cinema, though they note its technical limitations compared to contemporary European and American films. Recent critical analysis has focused on the film's role in constructing Mexican national identity and its pioneering use of religious iconography in cinema. Film scholars consider it an essential document for understanding the early development of Mexican film language and narrative techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Tepeyac was enormously popular with Mexican audiences upon its release in 1917. The film's combination of romance, international intrigue, and religious miracle resonated strongly with viewers who had experienced the turmoil of the revolution. Audiences particularly responded to the authentic depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the real locations of Tepeyac Hill. The film's success at the box office helped establish the commercial viability of feature-length Mexican films. Contemporary accounts describe emotional reactions from audiences, with many viewers reportedly weeping during the prayer sequences and cheering at the news of Roberto's survival. The film's popularity extended beyond Mexico City to provincial theaters, where it played for extended runs. Its success encouraged other Mexican producers to invest in feature films with national themes.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European religious epics

- American melodramas of the 1910s

- Italian historical films

- Traditional Mexican religious theater

- Contemporary war films about WWI

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Mexican films about the Virgin of Guadalupe

- 1930s Mexican religious dramas

- Mexican films combining modern and traditional themes

- Later Mexican films about faith and miracles

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Tepeyac is partially preserved with only fragments surviving. Some sequences exist in the Filmoteca de la UNAM in Mexico City, while other portions are held in international film archives. The film is considered partially lost, with approximately 40-50% of the original footage surviving. Restoration efforts have been undertaken by Mexican film preservationists, but the incomplete nature of surviving materials makes a full restoration impossible. The surviving fragments continue to be studied by film historians as important examples of early Mexican cinema.