The Cow

Plot

The Cow (Gāv) tells the story of Masht Hassan, an elderly villager in rural Iran who shares an unusually deep emotional bond with his cow, which represents his entire wealth and identity. When Hassan must temporarily leave his village to travel to the city, tragedy strikes as his beloved cow suddenly dies. The terrified villagers, knowing Hassan's profound attachment to the animal, conspire to conceal the death from him, burying the cow and telling him it wandered off. Upon his return, Hassan's desperate search for his missing cow leads to a complete psychological breakdown, as he begins to believe he has transformed into a cow himself, crawling on all fours, eating hay, and mooing. The film concludes tragically as the villagers, unable to cope with Hassan's deteriorating mental state, chain him up in a stable, where he eventually dies, leaving the community to grapple with their role in his demise.

About the Production

The film faced significant production challenges including limited funding, government censorship, and difficulties filming with the cow actors. Director Mehrjui had to use multiple cows to play the single role due to the animals' unpredictable behavior. The black and white cinematography was partly a budgetary necessity but became an artistic choice that enhanced the film's stark, realistic tone. The village location was carefully selected to represent traditional rural Iranian life, and many local villagers were used as extras, adding authenticity to the production.

Historical Background

The Cow emerged during a pivotal period in Iranian history, the late 1960s, when the country was undergoing rapid modernization under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's White Revolution. This era saw significant tension between traditional rural values and forced Westernization, creating social dislocation that the film subtly explores. The Iranian film industry was dominated by commercial 'Film Farsi' productions, often imitating Hollywood formulas with little artistic merit. Against this backdrop, a group of educated filmmakers, including Mehrjui, sought to create a new cinematic language that would reflect Iranian reality and culture. The film's production coincided with growing intellectual discontent with the Shah's regime and increasing awareness of social inequalities. Its focus on rural poverty and psychological breakdown was unprecedented in Iranian cinema and reflected the influence of European art cinema, particularly Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. The film's international recognition came at a time when Iran was trying to present a modern, cultured image to the world, even as internal repression increased. The subsequent banning of The Cow highlighted the contradictions of a regime that wanted international cultural prestige while suppressing critical voices at home.

Why This Film Matters

The Cow's impact on Iranian cinema cannot be overstated; it essentially birthed the Iranian New Wave and established a template for artistic filmmaking in the country. The film proved that Iranian stories, told with authenticity and artistic vision, could resonate with international audiences, paving the way for future masters like Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Its success challenged the dominance of commercial 'Film Farsi' and created space for more personal, socially conscious filmmaking. The film's portrayal of rural life and mental illness opened dialogues about topics previously considered taboo in Iranian society. Within Iranian culture, the film became a reference point for discussing the psychological impact of modernization and the loss of traditional ways of life. The character of Masht Hassan entered the cultural lexicon as a symbol of innocent victimhood and the fragility of the human psyche. The film's aesthetic influence can be seen in the minimalist, poetic realism that became hallmarks of Iranian cinema. Internationally, The Cow helped establish Iran as a serious contributor to world cinema, changing global perceptions of the country's cultural output. The film's restoration and continued screening in film festivals worldwide testify to its enduring significance as a masterpiece of world cinema.

Making Of

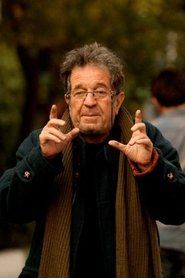

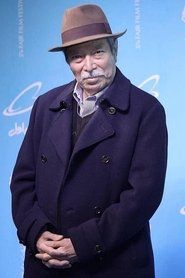

The making of The Cow was fraught with challenges that ultimately contributed to its legendary status. Director Dariush Mehrjui, then a young filmmaker with only one previous feature, struggled to secure funding for the project due to its unconventional subject matter. The film was shot on a shoestring budget over 38 days in a remote village, with the crew often facing harsh weather conditions and limited equipment. Mehrjui's decision to cast Ezzatollah Entezami, a stage actor with little film experience, proved inspired; Entezami prepared for the role by spending time in rural villages and studying the behavior of both cows and people suffering from mental illness. The production team faced constant pressure from government censors who demanded changes to the script, fearing the film's portrayal of rural poverty would reflect poorly on Iran. Remarkably, Mehrjui managed to complete the film largely as envisioned, though he had to make subtle compromises to avoid outright banning. The film's realistic style was enhanced by the decision to use local villagers as supporting actors and extras, many of whom had never seen a film camera before. The technical crew, working with outdated equipment, innovated solutions for lighting and sound that contributed to the film's raw, documentary-like aesthetic.

Visual Style

The Cow's black and white cinematography, executed by Nemat Haghighi, is renowned for its stark realism and poetic visual language. The camera work employs long takes and deep focus to create a documentary-like authenticity, placing viewers within the village environment. The use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes, enhances the film's connection to the rhythms of rural life. The framing often emphasizes the isolation of characters within the landscape, visually reinforcing their psychological states. The camera maintains a respectful distance during Hassan's breakdown, avoiding exploitation while still conveying the horror of his transformation. The contrast between the open spaces of the village and the confinement of the stable where Hassan is eventually chained creates a powerful visual metaphor for his psychological imprisonment. The cinematography avoids sentimentalizing poverty, instead presenting the village environment with unsparing clarity. The decision to shoot in black and white, partly necessitated by budget constraints, ultimately served the film's themes perfectly, stripping away distractions to focus on the essential human drama. The visual composition frequently employs low angles when filming Hassan, gradually reducing his stature as he loses his humanity. The cinematography's restrained style allows the emotional weight of the story to emerge naturally, creating a powerful cumulative effect.

Innovations

Despite its limited budget and resources, The Cow achieved remarkable technical innovations that influenced Iranian cinema for decades. The film's pioneering use of location shooting with non-professional actors helped establish a new standard for realism in Iranian filmmaking. The sound recording techniques developed for capturing authentic village sounds while maintaining clarity of dialogue were particularly innovative for Iranian cinema of the period. The cinematography achieved impressive results with minimal lighting equipment, using natural light and reflectors to create atmospheric scenes that still maintained visual clarity. The film's editing rhythm, which often holds on shots longer than conventional cinema, allows psychological states to emerge gradually through performance rather than cutting. The technical team developed creative solutions for filming with animals, a challenge that many larger productions struggle with even today. The film's successful balance of documentary realism with narrative construction demonstrated how limited resources could be turned into artistic advantages. The post-production techniques used to enhance the emotional impact of Hassan's psychological breakdown, particularly the subtle sound design choices, were groundbreaking for Iranian cinema. The film's preservation and restoration over the years have also provided valuable lessons in maintaining the integrity of classic Iranian films. The technical achievements of The Cow proved that artistic excellence was possible within the constraints of Iranian film production, inspiring future generations of filmmakers to pursue ambitious projects regardless of budget limitations.

Music

The film's sound design and musical score, created by Ahmad Pejman, play a crucial role in establishing its atmosphere and emotional impact. The minimal use of non-diegetic music reflects the film's realist aesthetic, with most of the soundtrack consisting of natural sounds from the village environment. The occasional musical passages employ traditional Persian instruments, subtly connecting the story to Iranian cultural heritage. The sound of the cow itself becomes a recurring motif throughout the film, initially representing Hassan's connection to his animal and later haunting his psychological breakdown. The film's most powerful audio moment comes when Hassan begins to mimic the cow's sounds, blurring the boundary between human and animal in a disturbing sonic transformation. The ambient sounds of the village - the wind, the calls to prayer, the daily activities - create an immersive environment that grounds the psychological drama in concrete reality. The sound design becomes increasingly important during Hassan's descent into madness, with the amplification of certain sounds and the muffling of others reflecting his altered perception. The film's final scenes use silence effectively to convey the tragedy of Hassan's isolation and death. The restrained approach to music and sound enhances the film's documentary feel while still providing emotional guidance for the audience. The soundtrack's minimalism perfectly complements the visual style, creating a unified aesthetic that serves the story's powerful themes.

Famous Quotes

Where is my cow? Where is my life? - Masht Hassan

A man without his cow is like a tree without roots - Village Elder

We did what we had to do. We did it for him - Villager

Sometimes the truth is more dangerous than a lie - Village Chief

When a man loses what he loves, he loses himself - Narrator

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence establishing Hassan's tender relationship with his cow, showing him grooming and talking to the animal with genuine affection

- The scene where villagers discover the cow's death and their panicked discussion about how to break the news to Hassan

- Hassan's return to the village and his growing desperation as he searches for his missing cow

- The powerful transformation scene where Hassan, believing he has become a cow, gets on all fours and begins eating hay

- The heartbreaking final sequence where villagers chain the broken Hassan in the stable, where he dies believing he is a cow

Did You Know?

- The Cow is widely regarded as the first film of the Iranian New Wave cinema movement, revolutionizing Iranian filmmaking with its realistic style and social commentary

- The film was banned in Iran shortly after its release by government authorities who felt it portrayed rural Iranian society in a negative light

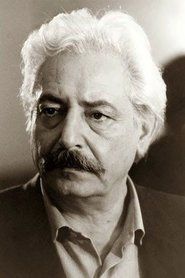

- Director Dariush Mehrjui adapted the screenplay from a short story by renowned Iranian writer Gholamhossein Saedi

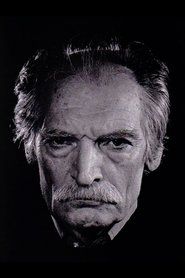

- Ezzatollah Entezami's performance as Masht Hassan is considered one of the greatest acting achievements in Iranian cinema history

- The film was Iran's first to gain significant international recognition, premiering at the Venice Film Festival and winning the FIPRESCI Prize

- Despite being made with minimal resources, the film's artistic merit earned it praise from international critics including François Truffaut

- The cow character was actually played by multiple different cows throughout filming due to the challenges of working with animals

- The film's success helped establish a new generation of Iranian filmmakers and proved that artistic films could be made in Iran despite censorship

- The movie was shot in chronological order to help Entezami maintain the psychological progression of his character's breakdown

- The film's title in Persian, 'Gāv,' became a cultural reference point in Iran for discussing mental illness and rural poverty

What Critics Said

Upon its international debut, The Cow received overwhelming critical acclaim, with reviewers praising its raw power, psychological depth, and social commentary. François Truffaut famously declared it 'the greatest film I've seen this year' and championed its distribution in France. International critics highlighted the film's universal themes while appreciating its specifically Iranian perspective. The film's black and white cinematography and naturalistic performances were particularly praised, with Entezami's portrayal of Masht Hassan described as 'devastatingly authentic.' Iranian critics were more divided initially, with some questioning the film's bleak portrayal of rural life, though many recognized its artistic breakthrough. Over time, Iranian critical opinion has solidified in favor of the film's importance, with it now being consistently ranked among the greatest Iranian films ever made. Contemporary critics continue to analyze the film's layered symbolism and its commentary on identity, community responsibility, and the psychological impact of modernization. The film's reputation has only grown over the decades, with it now being studied in film schools worldwide as a prime example of how national cinema can achieve both artistic excellence and universal relevance.

What Audiences Thought

The Cow initially had limited domestic theatrical release due to its controversial nature and subsequent banning, but among those who saw it, the film generated powerful reactions. Iranian audiences were shocked by its unflinching portrayal of rural poverty and mental illness, topics rarely addressed so directly in Iranian cinema. Many viewers reported being deeply moved by Entezami's performance and the film's tragic trajectory. In villages where it was screened, some audiences found the depiction too close to reality, while others appreciated seeing their lives reflected on screen with such dignity and complexity. The film's international festival audiences responded enthusiastically, often emotionally affected by its universal themes of loss and identity. Over the years, as the film became available through retrospectives and home video, its audience has grown, with younger generations of Iranians discovering it as a foundational work of their national cinema. The film continues to provoke strong reactions from viewers, many describing it as a haunting, unforgettable experience. Its reputation has spread through word of mouth and critical essays, making it a cult classic among cinephiles interested in world cinema. The film's power to affect audiences across cultures and decades testifies to the universality of its human drama.

Awards & Recognition

- FIPRESCI Prize (International Critics' Award) at the 1971 Venice Film Festival

- Best Film at the 1970 Sepas Film Festival (Iran)

- Best Director for Dariush Mehrjui at the 1970 Sepas Film Festival

- Best Actor for Ezzatollah Entezami at the 1970 Sepas Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly the works of De Sica and Rossellini)

- French New Wave cinema

- The works of Satyajit Ray

- Persian literature and storytelling traditions

- Documentary film techniques

- Existentialist philosophy

- Psychological realist literature

This Film Influenced

- The Cycle (1975) by Dariush Mehrjui

- The Runner (1985) by Amir Naderi

- A Time for Drunken Horses (2000) by Bahman Ghobadi

- Taste of Cherry (1997) by Abbas Kiarostami

- The Color of Paradise (1999) by Majid Majidi

- A Separation (2011) by Asghar Farhadi

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Cow has been preserved and restored by various film archives including The Criterion Collection and the Cineteca di Bologna. The original negative was stored in poor conditions for years but was successfully restored in the 1990s. A 4K restoration was completed in 2018, ensuring the film's survival for future generations. The restored version has been screened at major film festivals including Cannes and Venice, bringing this classic to new audiences. The film is now part of the permanent collections of several prestigious film archives including the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modern Art.