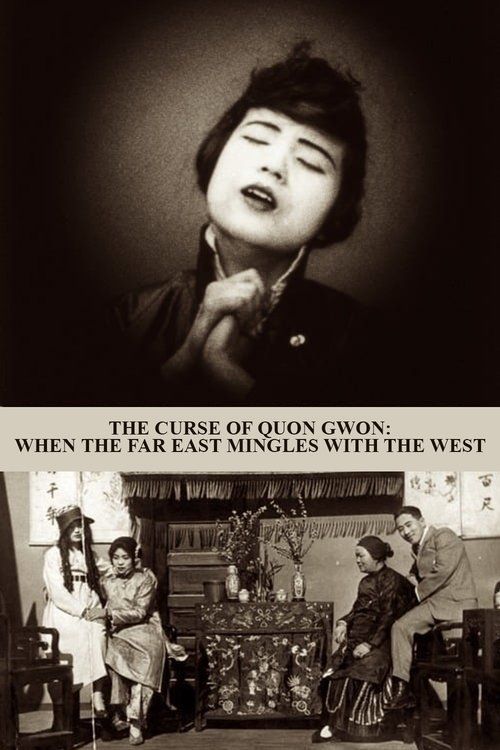

The Curse of Quon Gwon: When the Far East Mingles with the West

Plot

The Curse of Quon Gwon tells the story of a Chinese family grappling with the supernatural consequences of assimilation into Western culture. The plot centers on a curse from a Chinese deity that follows the family members as they adopt Western customs and values in America. The narrative explores the tensions between traditional Chinese heritage and the allure of American modernization, particularly through the experiences of young Chinese-Americans navigating between two worlds. The surviving footage suggests a complex family drama involving romance, cultural conflict, and the struggle to maintain identity in a new society. The film's title character appears to be central to the supernatural elements, with the curse manifesting as the family increasingly embraces Western lifestyle.

Director

About the Production

Marion E. Wong established the Chinese-American Film Company specifically to produce this film, making her one of the first Chinese-American women to found a film production company. The film was shot with an all-Chinese cast, revolutionary for its time when Chinese roles were typically played by white actors in yellowface. Production took place over several months in 1916 with Wong serving as director, writer, producer, and actress. The film was reportedly shot on location in Oakland's Chinatown and surrounding areas, utilizing authentic Chinese-American settings rather than studio backlots.

Historical Background

The Curse of Quon Gwon was created during a period of intense anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was still in effect and would not be repealed until 1943, severely limiting Chinese immigration and citizenship. Chinese-Americans faced widespread discrimination, segregation, and violence, particularly in California where the film was made. The silent film era was dominated by white filmmakers, and when Asian characters appeared, they were typically played by white actors in yellowface makeup, perpetuating harmful stereotypes. Against this backdrop, Marion E. Wong's decision to create an authentic Chinese-American film with an all-Chinese cast was revolutionary. The film emerged during the early feature film boom when Hollywood was transitioning from short films to longer narratives. It was also a time when women were relatively prominent as directors in the industry, before they would be systematically marginalized by the studio system. The film's exploration of cultural assimilation reflected the real struggles of Chinese-Americans trying to maintain their heritage while adapting to American life.

Why This Film Matters

The Curse of Quon Gwon represents a landmark achievement in American cinema history as the earliest known feature film made by and about Chinese-Americans. Its existence challenges the narrative that Asian-Americans were absent from early filmmaking, demonstrating that they were not only present but actively creating their own stories. The film's authentic representation of Chinese-American life stands in stark contrast to the stereotypical portrayals that dominated Hollywood productions of the era. Marion E. Wong's achievement as a young Chinese-American woman director in 1916 is extraordinary, predating many celebrated women filmmakers by years. The film's themes of cultural identity and assimilation remain relevant today, speaking to ongoing immigrant experiences in America. Its rediscovery and preservation have allowed film scholars to rewrite aspects of cinema history, acknowledging the contributions of Asian-American pioneers. The film serves as a testament to the resilience and creativity of marginalized communities in the face of systemic exclusion from mainstream culture.

Making Of

The production of The Curse of Quon Gwon was a remarkable achievement against formidable odds. Marion E. Wong, a recent graduate of high school, decided to create a film that would authentically represent Chinese-American life without resorting to the caricatures prevalent in Hollywood at the time. She convinced her family to invest in the project, with her husband serving as cinematographer. The film was made with a completely Chinese cast and crew, virtually unprecedented in 1916. Wong not only directed but also wrote the screenplay and acted in the film. The production faced numerous challenges, including securing equipment on a limited budget and finding locations that could authentically represent Chinese-American life. The surviving footage suggests a professional approach to filmmaking, with careful composition and lighting techniques that indicate Wong had studied contemporary cinema. The film's post-production process would have included creating intertitles, but none of these survive, making it impossible to know the exact dialogue or scene descriptions. After completing the film, Wong struggled to find distributors willing to take a chance on an authentic Chinese-American story without the expected stereotypes, leading to the film's commercial failure despite its artistic merits.

Visual Style

The surviving footage of The Curse of Quon Gwon demonstrates competent and thoughtful cinematography for its time. The film appears to have been shot using available natural light in many scenes, creating authentic atmospheres in the Chinese-American settings. The camera work shows understanding of contemporary cinematic techniques, including varied shot compositions and movement that enhance the storytelling. Interior scenes utilize careful lighting to create mood and focus attention on the actors. The cinematography successfully captures the visual details of Chinese-American life in the 1910s, from traditional clothing to household objects and architectural elements. The film's visual style appears more naturalistic than many Hollywood productions of the era, avoiding the artificial lighting and staging common in studio films. The camera work suggests a documentary-like attention to authentic details, particularly in scenes showing Chinese cultural practices and environments. Despite the fragmentary nature of what survives, the cinematography reveals Marion E. Wong's sophisticated visual sense and her ability to use the camera to tell stories with emotional depth and cultural specificity.

Innovations

The Curse of Quon Gwon represents several significant technical achievements for its time and context. Marion E. Wong demonstrated sophisticated understanding of film language and narrative construction, particularly impressive given her youth and limited resources. The film's use of location shooting rather than studio sets was relatively advanced for an independent production of this era. The surviving footage shows competent use of editing techniques to create dramatic tension and emotional impact. The film's creation by an all-Chinese cast and crew was technically groundbreaking in an industry dominated by white practitioners. The preservation of the surviving nitrate film stock presented significant technical challenges, requiring specialized restoration processes to prevent further deterioration and make the footage accessible for modern viewing. The Academy Film Archive's preservation work involved cleaning, repairing, and creating safety copies of the deteriorating nitrate material, ensuring the film's survival for future generations. The film's technical quality, despite its independent status and limited budget, demonstrates Wong's commitment to professional filmmaking standards.

Music

As a silent film, The Curse of Quon Gwon would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its original screenings. The specific musical selections or original compositions used are unknown, as no documentation survives about the film's musical accompaniment. Typical practice for films of this era would have included a pianist or small orchestra providing background music, possibly using popular pieces of the time or classical selections appropriate to the film's mood. Given the film's Chinese-American themes, it's possible that traditional Chinese music may have been incorporated into the score, though this would have been unusual for American theaters of the period. Modern screenings of the surviving fragments typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period music that complements the film's cultural context. The Academy Film Archive's preservation work has not included recreating the original musical accompaniment, as no information survives about what was used during the film's initial screenings.

Famous Quotes

No direct quotes survive due to the loss of intertitles and the film's silent nature

Memorable Scenes

- Surviving footage shows what appears to be a traditional Chinese wedding ceremony, with authentic costumes and rituals rarely captured in American films of the era

- A dramatic scene featuring the supernatural manifestation of the curse, with visual effects that were sophisticated for an independent production

- Domestic scenes showing Chinese-American family life, providing rare visual documentation of how Chinese households maintained traditions in America

- Outdoor scenes filmed in Oakland's Chinatown, capturing the architectural and cultural details of early Chinese-American communities

Did You Know?

- This is the oldest known Chinese-American feature film ever made, predating other Asian-American cinema by decades

- Marion E. Wong was only 21 years old when she directed this film, making her one of the youngest feature film directors of the silent era

- The film was lost for nearly 90 years until its rediscovery in 2004 in the basement of a Chinese-American family's home

- The two surviving reels were found in a deteriorating condition and required extensive restoration by the Academy Film Archive

- No intertitles survive with the film, making the exact dialogue and narrative details impossible to determine definitively

- The film was rejected by distributors specifically because it didn't include the racial stereotypes that audiences expected in Chinese-themed films of the era

- Marion E. Wong founded her own production company, the Chinese-American Film Company, specifically to make this film

- The film was only screened publicly three times during its initial release: once at its premiere and twice more before disappearing

- The Academy Film Archive preserved the film in 2005, and it was added to the National Film Registry in 2006 for its cultural significance

- The cast included Wong's own sister-in-law Violet Wong in the leading role, showcasing family involvement in the production

- Contemporary advertisements described it as 'the first and only Chinese picture made in America by Chinese company'

- The film's failure reportedly discouraged Marion E. Wong from pursuing further filmmaking projects

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Curse of Quon Gwon is largely unknown due to the film's extremely limited distribution and the lack of surviving reviews from its time. The Moving Picture World did provide a brief description in its July 17, 1917 issue, noting that the film "deals with the curse of a Chinese god that follows his people because of the influence of western civilization," but offered no critical assessment. Modern critics and film historians have hailed the film as a groundbreaking discovery upon its rediscovery. The Academy Film Archive and preservation specialists have praised its technical quality and artistic merit, noting Wong's sophisticated use of cinematic techniques. Film scholars have emphasized its importance as a counter-narrative to the racist depictions common in period cinema. The film's selection for the National Film Registry in 2006 reflects its critical recognition as a work of historical and cultural importance. Contemporary critics have lamented that only fragments survive, but celebrate what remains as evidence of early Asian-American cinematic achievement.

What Audiences Thought

The audience reception of The Curse of Quon Gwon during its initial release was minimal due to its extremely limited theatrical run. The film was screened only three times publicly, suggesting it reached very few viewers. Contemporary audience reactions are not documented, likely because the film never achieved wide distribution. The lack of distributor interest indicates that industry professionals believed mainstream audiences would not be interested in an authentic Chinese-American story without the expected stereotypes. Modern audiences have had limited opportunities to view the film due to its fragmentary survival, but those who have seen the preserved portions at special screenings and film festivals have responded with fascination and appreciation for its historical significance. The film's rediscovery has generated considerable excitement within Asian-American communities and film preservation circles, with many expressing pride in this evidence of early Chinese-American filmmaking achievement. The surviving footage has been featured in documentary programs and museum exhibitions, where it has been received as an important cultural artifact.

Awards & Recognition

- Added to the National Film Registry in 2006 for being culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary Hollywood melodramas

- Chinese traditional folklore and mythology

- D.W. Griffith's narrative film techniques

- Early American independent cinema

- Chinese theatrical traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Asian-American independent films

- Modern Chinese-American cinema

- Contemporary films exploring cultural assimilation

- Documentaries about early Asian-American history

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - Only two of the original reels survive (approximately 35 minutes of footage). The film was considered lost until its rediscovery in 2004 in the basement of a Chinese-American family's home in Oakland. The Academy Film Archive preserved the surviving nitrate material in 2005 through a complex restoration process. The film was selected for the National Film Registry in 2006, recognizing its cultural significance despite its incomplete state. No intertitles survive with the footage, making complete understanding of the narrative impossible. The preserved elements are stored at the Academy Film Archive and occasionally screened at special events and film festivals. The surviving footage represents one of the earliest examples of Chinese-American cinema and remains a priceless artifact of film history.