The Danger Game

"She wrote about crime - then lived it!"

Plot

Wealthy society girl Clytie Rogers writes a novel about a high-society burglar, but her work is brutally criticized by newspaper reviewer Jimmy Gilpin who declares her plot completely implausible. Determined to prove her story's credibility, Clytie attempts to stage a real burglary by climbing through an apartment window, only to be immediately arrested by police who mistake her for the notorious local thief known as 'Powder Nose Annie.' When Gilpin discovers her in jail, he adopts a criminal persona as 'Jimmy of the Dives' and orchestrates her escape, taking her on a mock crime spree to teach her about the reality of criminal life. After their adventure concludes, Gilpin safely returns Clytie to her parents and then visits her home as his true self, the critic, where a surprised but understanding Clytie forgives his deception and accepts his marriage proposal.

About the Production

The Danger Game was produced during the final months of World War I and released just as the Spanish Flu pandemic was beginning to sweep across America. The film was one of several vehicles designed to showcase Madge Kennedy's comedic talents, who was one of Realart Pictures' biggest stars. The production utilized the growing studio system in Los Angeles, taking advantage of the established infrastructure for silent film production. The film's five-reel structure was typical for feature comedies of the era, allowing for sufficient character development while maintaining a brisk pace suitable for the comedy genre.

Historical Background

The Danger Game was produced and released during a pivotal moment in world history, arriving in theaters in September 1918, just two months before the end of World War I. The film industry itself was undergoing significant transformation, with Hollywood firmly established as the center of American film production. This period saw the consolidation of the studio system and the rise of the star system, with actors like Madge Kennedy becoming valuable commodities for their respective studios. The film's release also coincided with the beginning of the devastating 1918 influenza pandemic, which would claim millions of lives worldwide and significantly affect public life, including movie theater attendance. The comedy genre was particularly important during this time as it offered audiences escape from the stresses of war and the growing health crisis. The film's themes of social experimentation and role reversal reflected broader cultural discussions about changing gender roles and social hierarchies in the post-Victorian era.

Why This Film Matters

The Danger Game represents an important example of the sophisticated comedy genre that was emerging in American cinema during the late 1910s. The film's premise of a wealthy woman experiencing life as a criminal tapped into contemporary fascination with social mobility and class boundaries in America. As a vehicle for Madge Kennedy, one of the era's most popular comediennes, it contributed to the development of the female-led comedy genre that would later be perfected by stars like Carole Lombard and Katharine Hepburn. The film's exploration of the relationship between fiction and reality through the novelist protagonist mirrored growing public awareness of the power of media and storytelling in shaping public perception. While the film itself may be lost, its existence demonstrates the sophistication of narrative storytelling that had developed in American cinema by 1918, moving beyond simple slapstick toward more character-driven comedy with social commentary.

Making Of

The Danger Game was created during a transitional period in American cinema when feature films were becoming the industry standard over short subjects. Madge Kennedy, having established herself as a comedy star through stage work and earlier films, was given significant creative input in her projects. The film's production took advantage of the sophisticated studio facilities that had been developed in Los Angeles by 1918. Director Harry A. Pollard, who had begun as an actor in 1912, brought his understanding of comedic timing to the project. The production team faced the typical challenges of the silent era, including the need for exaggerated facial expressions and gestures to convey emotion and comedy without dialogue. The jailbreak sequences required careful coordination and planning, as special effects were limited to practical methods during this period.

Visual Style

The cinematography for The Danger Game was handled by Arthur Edeson, who was in the early stages of what would become a legendary career. While the film itself is lost, Edeson's work from this period demonstrates the sophisticated visual techniques that were being developed in American cinema by 1918. The film likely employed the standard lighting setups of the era, using natural light when possible and artificial lighting to create dramatic effects. The jail sequences would have required careful lighting to create the appropriate atmosphere while ensuring the actors' expressions remained visible. The exterior scenes, including the window-climbing sequence, would have utilized the California sunlight that had made Los Angeles attractive to filmmakers. Edeson's later work suggests he would have employed dynamic camera movement and interesting angles even in this early comedy.

Innovations

While The Danger Game does not appear to have introduced any revolutionary technical innovations, it employed the sophisticated filmmaking techniques that had become standard by 1918. The film likely utilized multiple camera setups to capture different angles within scenes, a technique that had become common but was still relatively new. The production would have benefited from the improved film stock available by 1918, which offered better image quality and reduced flicker compared to earlier films. The jailbreak sequence would have required careful planning and execution, possibly involving miniatures or matte shots for certain effects. The film's five-reel structure allowed for more complex storytelling than earlier shorts, demonstrating the technical capabilities that had been developed for feature-length productions by this time.

Music

As a silent film, The Danger Game would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The score would have been compiled from various sources including classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and specially composed cue sheets. The music would have been synchronized with the on-screen action, with romantic themes for the scenes between Clytie and Jimmy, suspenseful music for the criminal sequences, and upbeat, playful melodies for the comedic moments. The specific musical selections for this film are not known due to its lost status, but theaters of the era typically employed either piano accompaniment for smaller venues or full orchestras for premier showings in larger cities. The music would have played a crucial role in conveying the film's shifting tones from comedy to romance to mild thriller.

Famous Quotes

Your story is completely implausible - no society girl would ever commit a burglary!

I'll show you what's plausible, Mr. Critic!

They call me Jimmy of the Dives - and you're my new partner in crime.

All this to prove a point? You're either very brave or very foolish, my dear.

Sometimes the best stories are the ones we live, not the ones we write.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Jimmy Gilpin harshly criticizes Clytie's novel in his newspaper column

- Clytie's clumsy attempt to climb through the apartment window in her society clothes

- The jail scene where Jimmy, disguised as a criminal, arranges Clytie's escape

- The mock crime spree where Jimmy teaches Clytie the 'realities' of criminal life

- The final revelation scene where Jimmy appears at Clytie's home as himself, the critic

Did You Know?

- The film is now considered lost, with no known surviving copies in any film archives worldwide.

- Madge Kennedy was one of the highest-paid actresses of the 1910s, earning $1,000 per week at the height of her fame.

- Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, who worked on this film, would later become one of Hollywood's most respected cinematographers, shooting classics like Casablanca (1942) and The Big Sleep (1946).

- The story was written by Margaret Turnbull, who would go on to write for over 60 films during her career.

- Realart Pictures Corporation was originally formed to distribute Paramount Pictures films but later began producing its own features.

- The film's release coincided with the 1918 influenza pandemic, which likely affected its theatrical run and box office performance.

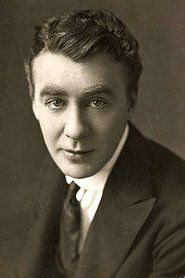

- Tom Moore, who plays Jimmy Gilpin, was one of five brothers who all worked in Hollywood as actors and directors.

- Director Harry A. Pollard would later direct the 1936 film version of Show Boat, one of the first major Hollywood productions with an integrated cast.

- The character name 'Powder Nose Annie' was a common slang term in the 1910s for women who used excessive makeup, particularly cocaine users.

- The film's theme of a society woman slumming it for adventure was a popular trope in silent comedies of the late 1910s.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of The Danger Game were generally positive, with critics particularly praising Madge Kennedy's comedic performance and her ability to carry the film's somewhat far-fetched premise. The Motion Picture News noted that Kennedy 'brings her usual charm and wit to the role, making the unbelievable plot entirely palatable.' Variety commented on the film's 'clever construction and well-timed comedy sequences,' though some critics found the resolution somewhat contrived. Modern critical assessment is impossible due to the film's lost status, but film historians consider it an important example of Kennedy's work and the sophisticated comedy genre of the late 1910s. The film is frequently referenced in studies of lost cinema and the work of its cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, during his formative years.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Danger Game appears to have been favorable based on contemporary trade publication reports. The film capitalized on Madge Kennedy's established popularity with audiences, who had come to expect clever comedies from the star. Movie theaters in major cities reported good attendance for the film during its initial run, though the timing of its release during the beginning of the 1918 influenza pandemic likely limited its overall box office success. The film's theme of a society woman engaging in criminal activity resonated with audiences' fascination with the criminal underworld, which was a popular subject in films of the era. The romantic subplot between Kennedy and Moore's characters provided the emotional resolution that audiences of the period expected from comedy features.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The tradition of society comedies from the stage

- Earlier films about class crossing such as 'The Poor Little Rich Girl' (1917)

- The popular 'rags-to-riches' narratives of the era

- Contemporary fascination with criminal underworld stories

This Film Influenced

- Later society comedy films of the 1920s

- Films featuring female protagonists in criminal situations

- Romantic comedies involving deception and mistaken identity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Danger Game is considered a lost film. No copies are known to exist in any film archives or private collections worldwide. This status is unfortunately common for films from the late 1910s, as an estimated 75-90% of American silent films have been lost due to the unstable nature of early nitrate film stock, improper storage, and the destruction of films when their commercial value expired. The film is listed among the lost titles in the Library of Congress's database of American silent feature films, and it is sought after by film archivists and historians, particularly due to its connection to cinematographer Arthur Edeson and star Madge Kennedy.