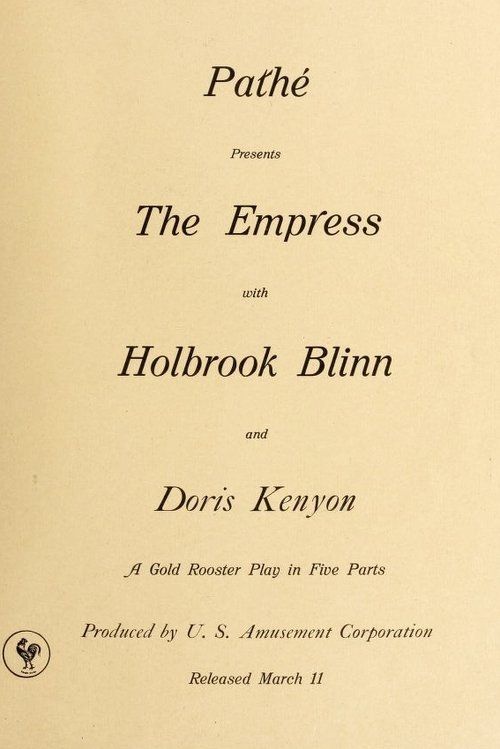

The Empress

Plot

Artist DeBaudry creates a successful painting titled 'The Empress' using Nedra as his model. After the painting's triumph, DeBaudry takes Nedra to celebrate at a roadhouse, where he deceptively registers them as Mr. and Mrs. without her knowledge. The roadhouse proprietor, who secretly operates as a blackmailer, photographs the couple together, setting up a scheme for extortion. This compromising photograph becomes the central conflict as Nedra's reputation and future are threatened by the artist's reckless actions and the proprietor's criminal intentions. The drama unfolds as Nedra must navigate the consequences of being placed in this compromising position through no fault of her own.

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during Alice Guy-Blaché's later period at Solax Studios in Fort Lee, which was then the center of American film production before the industry moved to Hollywood. The film showcases Guy-Blaché's sophisticated understanding of narrative structure and character development, particularly in her portrayal of female characters facing moral dilemmas. The roadhouse setting was a common trope in melodramas of the era, representing spaces of moral ambiguity and social danger.

Historical Background

The Empress was released in 1917, during a pivotal moment in world history as World War I raged in Europe. This period saw significant changes in the American film industry, including the gradual shift from independent studios to the studio system that would dominate Hollywood. Alice Guy-Blaché, having emigrated from France, represented the international nature of early cinema. The film's themes of blackmail and compromised virtue reflected contemporary social anxieties about women's changing roles in society and the dangers they faced in an increasingly modern world. 1917 also saw the United States' entry into World War I, which influenced film content and production across the industry. The film industry itself was undergoing technological and artistic evolution, with longer feature films becoming more common and narrative techniques growing more sophisticated.

Why This Film Matters

As a work directed by one of cinema's pioneering female filmmakers, The Empress represents an important piece of film history that highlights women's crucial role in early cinema development. Alice Guy-Blaché's films, including this one, challenged contemporary gender norms both through their existence and their content. The film's focus on a female protagonist facing moral and social dilemmas reflects Guy-Blaché's consistent interest in women's perspectives and experiences. The preservation and study of such films is crucial for understanding the full scope of early cinema and correcting the historical record that has often marginalized women's contributions to the medium. The film also exemplifies the sophisticated narrative techniques being developed in American cinema during the 1910s, demonstrating how quickly the art form was evolving in its first two decades.

Making Of

Alice Guy-Blaché directed this film during her tenure running Solax Studios, which she had established in 1910. The studio was known for its progressive treatment of women both on and off screen, with Guy-Blaché often employing female actresses in complex, non-stereotypical roles. The film's production took advantage of the sophisticated facilities at Fort Lee, including elaborate indoor sets that could simulate the roadhouse environment. Guy-Blaché was known for her hands-on approach to directing, often working closely with actors to develop nuanced performances. The casting of Doris Kenyon, who was then an emerging talent, demonstrates Guy-Blaché's eye for spotting future stars. The film's themes of female vulnerability and male deception were characteristic of Guy-Blaché's interest in exploring social issues through melodrama.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Empress would have utilized the techniques common to sophisticated productions of 1917, including careful composition and lighting to enhance the dramatic narrative. Alice Guy-Blaché was known for her innovative use of camera angles and movement, and this film likely featured her characteristic attention to visual storytelling. The roadhouse scenes would have employed dramatic lighting to create atmosphere and tension, while the painting sequences might have featured more artistic, composed shots. The film would have been shot on black and white film stock, with tinting possibly used for emotional effect in certain scenes, a common practice in the 1910s.

Innovations

The Empress represents the state-of-the-art filmmaking of 1917, utilizing the advanced facilities of Solax Studios. Alice Guy-Blaché was known for her technical innovations, and this film likely featured sophisticated editing techniques for its time, including cross-cutting to build suspense during the blackmail sequences. The film's production would have taken advantage of Solax's electric lighting systems, allowing for more controlled and dramatic lighting than was possible with natural light. The use of interior sets to simulate the roadhouse environment demonstrates the growing sophistication of production design in American cinema. Guy-Blaché was also an early experimenter with synchronized sound, though this film was produced as a traditional silent feature.

Music

As a silent film, The Empress would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The score would have been provided by a theater's organist or pianist, often using compiled cue sheets or original compositions. The music would have been carefully synchronized with the on-screen action to enhance emotional impact, with dramatic themes for the blackmail plot and romantic motifs for the artist-model relationship. Theaters of this period often employed small orchestras for major productions, and given the sophistication of Guy-Blaché's work, The Empress likely received musical treatment appropriate to its dramatic content.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue survives from this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The pivotal scene where the roadhouse proprietor secretly photographs the couple, capturing the moment of deception that drives the entire narrative conflict

Did You Know?

- Alice Guy-Blaché was one of the first female film directors in history and possibly the first to direct a narrative film in 1896

- This film was produced during World War I, which significantly impacted the film industry and themes of the era

- Doris Kenyon, who plays Nedra, would go on to have a long career in both silent and sound films, spanning over three decades

- The film was shot in Fort Lee, New Jersey, which was known as the birthplace of the American motion picture industry

- Alice Guy-Blaché's Solax Studios was one of the largest and most technologically advanced film studios of its time

- The theme of blackmail was particularly relevant in 1917, as it was a common plot device reflecting real social anxieties of the period

- This film represents Guy-Blaché's later American period, after she had already directed hundreds of films in France

- The title 'The Empress' refers both to the painting within the film and metaphorically to themes of power and vulnerability

- Roadhouse settings in films of this era often represented the liminal space between respectability and danger

- Alice Guy-Blaché is credited with pioneering many film techniques including close-ups, synchronized sound experiments, and narrative storytelling

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of The Empress are scarce, as was common for many films of this era, particularly those from independent studios. However, Alice Guy-Blaché's work during this period was generally well-regarded by trade publications for its technical proficiency and storytelling capabilities. Modern film historians and critics have come to recognize the importance of Guy-Blaché's entire body of work, including films like The Empress, as crucial to understanding early cinema's development. The film is often cited in scholarly discussions about women's roles in early Hollywood and the evolution of narrative film techniques. Contemporary feminist film scholars have reexamined Guy-Blaché's work, finding sophisticated treatments of gender and power dynamics that were ahead of their time.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception records from 1917 are limited, but films dealing with themes of moral compromise and blackmail were popular with contemporary audiences. The melodramatic elements and clear moral framework would have appealed to the sensibilities of early 20th-century moviegoers. Alice Guy-Blaché had built a reputation for producing engaging, well-crafted films that satisfied both critics and audiences. The presence of emerging star Doris Kenyon likely attracted additional viewers. The film's themes would have resonated with audiences navigating the rapidly changing social landscape of America during World War I, particularly regarding women's roles and social expectations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary melodramatic traditions

- French narrative cinema

- American social problem films

- Stage melodrama conventions

This Film Influenced

- Later films dealing with blackmail themes

- Women-centered dramas of the 1920s

- Films exploring artist-model relationships

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Empress is considered a lost film, as are approximately 90% of films from this era. No complete prints are known to exist in major film archives. This loss is particularly significant given its status as one of Alice Guy-Blaché's later American works. Fragments or still photographs may exist in private collections or archives, but the complete film has not survived. The loss of this and other Guy-Blaché films represents a significant gap in cinema history, particularly regarding women's contributions to early filmmaking.