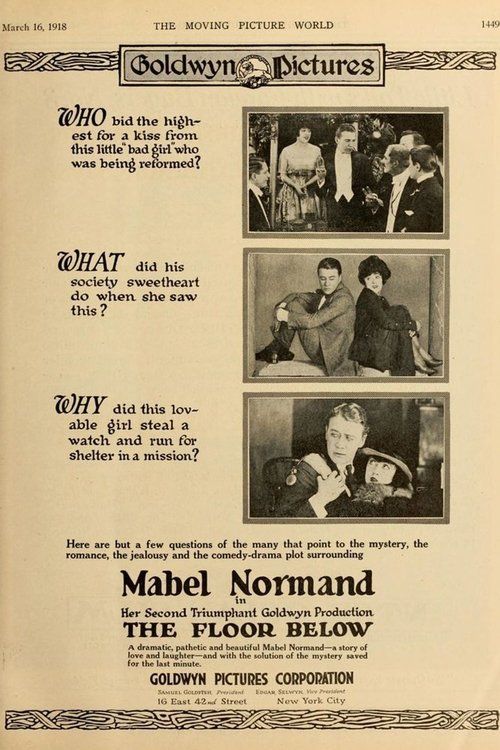

The Floor Below

"A Girl Who Dared to Be Different!"

Plot

Patricia O'Rourke, a spirited prankster working as a copy girl for the Sentinel newspaper, faces termination after angering her colleague Stubbs with her mischievous antics. The managing editor, giving her one final opportunity, assigns her to investigate the mysterious connection between the Hope Mission, a charitable institution run by wealthy philanthropist Hunter Mason and his secretary Monty Latham, and a series of local robberies plaguing the community. When Patricia attempts to gather information by sneaking into Hunter's office, he discovers her presence and mistakenly believes she's a criminal in desperate need of rehabilitation. Rather than turning her over to authorities, Hunter takes the bewildered Patricia into his luxurious home, where his mother is tasked with reforming the supposed wayward girl. As Patricia navigates this unexpected situation, she continues her investigation while trying to maintain her cover, leading to comedic misunderstandings and eventually uncovering the true connection between the mission and the crimes.

About the Production

The film was produced during the transition period when Mabel Normand was moving from Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios to more dramatic feature films. Clarence G. Badger, who had directed Normand in several successful shorts, was chosen to helm this feature to help ease her transition. The production faced some challenges due to the ongoing World War I, with some male cast members being called for military service during filming, requiring schedule adjustments.

Historical Background

The Floor Below was produced during a pivotal moment in American cinema history, as the film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions and the center of filmmaking was shifting from the East Coast to Hollywood. 1918 was the final year of World War I, and films of this period often reflected themes of patriotism, sacrifice, and social reform. The Spanish Flu pandemic was sweeping across the globe, affecting both production and exhibition of films. This was also the era when women were gaining more prominence in Hollywood, both on screen and behind the camera, with figures like Mabel Normand and screenwriter June Mathis breaking barriers in a male-dominated industry. The film's setting in a newspaper office reflected the growing importance of journalism in American society and the public's fascination with the press as a force for social change. The Hope Mission element of the story tapped into the Progressive Era's focus on social reform and charitable institutions that were working to address urban poverty and inequality.

Why This Film Matters

The Floor Below represents an important transitional work in Mabel Normand's career and in the broader evolution of American comedy cinema. As one of the first feature films to showcase Normand's talents beyond slapstick, it demonstrated the potential of comedy stars to succeed in more dramatic roles, paving the way for future actors to cross genre boundaries. The film's exploration of social class issues through the lens of comedy reflected the growing sophistication of American cinema and its willingness to address contemporary social concerns. The newspaper setting also contributed to the popular genre of journalism films that would flourish throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Additionally, the film's production during wartime and its themes of redemption and understanding between social classes resonated with audiences seeking entertainment that also offered hope and moral clarity during turbulent times.

Making Of

The production of 'The Floor Below' represented a significant career milestone for Mabel Normand, who was attempting to establish herself as a serious dramatic actress after years of success in slapstick comedy at Keystone Studios. Director Clarence G. Badger, who understood Normand's strengths and comedic timing, worked carefully to balance her natural comedic talents with the more dramatic elements of the story. The film was shot at Goldwyn's facilities in Fort Lee, New Jersey, which was then the center of American film production before the industry's migration to Hollywood. During filming, the cast and crew dealt with the challenges of wartime production, including material shortages and the constant threat of cast members being drafted. The chemistry between Normand and leading man Tom Moore was considered strong enough that they were paired again in subsequent films. The production design emphasized the contrast between the newspaper office environment and the luxurious world of Hunter Mason, using this visual dichotomy to reinforce the film's themes of social class and opportunity.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Floor Below' was handled by Arthur Edeson, who would later become one of Hollywood's most respected cinematographers. The film employed the visual style typical of late 1910s features, with relatively static camera positions but careful composition to emphasize the contrast between the cramped newspaper office and the spacious Mason mansion. Edeson used lighting to create mood and distinguish between different social environments, with the Hope Mission scenes featuring softer, more naturalistic lighting compared to the dramatic chiaroscuro effects in the mystery sequences. The film also utilized some location photography in New York City to establish its urban setting, a practice that was becoming more common as productions moved away from exclusively using studio sets.

Innovations

While 'The Floor Below' was not particularly innovative technically, it represented solid craftsmanship typical of Goldwyn Pictures productions in 1918. The film utilized multiple camera setups within scenes, which was becoming standard practice but still represented an advancement over earlier single-camera techniques. The production design effectively created distinct visual worlds for different social classes, using set decoration and lighting to reinforce the film's themes. The editing节奏 (rhythm) balanced the comedic and dramatic elements effectively, allowing Normand's comedic timing to shine while maintaining the mystery narrative's momentum. The film also demonstrated effective use of intertitles to convey both dialogue and exposition, a crucial element in silent film storytelling that was becoming increasingly sophisticated during this period.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Floor Below' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a theater organist or small orchestra providing musical accompaniment that followed the action and mood of each scene. For newspaper office sequences, upbeat, rhythmic music would have been used, while romantic scenes between Normand and Moore would have featured more melodic, sentimental themes. The mystery elements would have been underscored with dramatic, tension-building music. While no original score survives, contemporary accounts suggest that Goldwyn Pictures provided musical cue sheets to theaters to ensure consistent accompaniment across different venues.

Famous Quotes

I'm not a crook, I'm a copy girl!

One more chance, that's all I ask!

Sometimes the best stories are found in the most unexpected places

Reform me? I think you're the one who needs reforming!

Memorable Scenes

- Patricia's initial confrontation with Stubbs in the newspaper office where her prank goes wrong

- The scene where Hunter discovers Patricia in his office and mistakes her for a criminal

- Patricia's awkward dinner with Hunter's mother where she tries to maintain her cover

- The climactic revelation of the true connection between the Hope Mission and the robberies

- Patricia's final scene where she proves her worth as both a reporter and a reformed character

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first feature films that Mabel Normand made after leaving Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios, marking her transition from short comedy films to dramatic features

- The film was released just two months before the end of World War I, and its themes of redemption and second chances resonated with wartime audiences

- Clarence G. Badger had previously directed Mabel Normand in the popular Mickey series of short films, and their successful collaboration led to this feature-length project

- The Hope Mission depicted in the film was based on actual settlement houses and charitable institutions that were common in major American cities during the early 20th century

- Tom Moore, who played Hunter Mason, was one of five brothers who all became successful actors in silent films

- The film's title 'The Floor Below' refers both literally to the physical location of the Hope Mission below the main offices and metaphorically to the social class divisions explored in the story

- This film is considered lost, with no known surviving copies in any film archive or private collection

- The original screenplay was written by June Mathis, who would later become one of the most powerful women in Hollywood and discover Rudolph Valentino

- Mabel Normand performed her own stunts in the film, including a scene where she climbs down a fire escape, continuing her tradition of physical comedy from her Keystone days

- The film's production coincided with the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, which caused some filming delays and affected the theatrical release schedule

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'The Floor Below' were generally positive, with critics praising Mabel Normand's successful transition to feature films and her ability to balance comedy with dramatic elements. The Motion Picture News noted that 'Miss Normand proves she has the dramatic talent to match her proven comedic abilities,' while Variety called it 'an entertaining picture that should please her many fans.' The New York Times review highlighted the film's 'clever mixture of humor and pathos' and praised Clarence Badger's direction for maintaining a consistent tone throughout. Modern critics have been unable to evaluate the film directly due to its lost status, but film historians consider it an important work in Normand's filmography and a significant example of the transitional cinema of the late 1910s.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1918 responded positively to 'The Floor Below,' with the film performing well in major urban markets where Mabel Normand had a strong fan base from her Keystone days. The combination of comedy, mystery, and romance appealed to wartime audiences seeking escapist entertainment with emotional depth. Contemporary trade papers reported that theater owners were pleased with the film's drawing power, particularly among female audiences who connected with Normand's character of an independent working woman. The film's success helped establish Normand as a bankable feature film star and demonstrated that audiences would accept comedy stars in more serious roles. However, the film's reception was somewhat overshadowed by the ongoing war and the Spanish Flu pandemic, which affected theater attendance in many markets during its release period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mabel Normand's earlier work at Keystone Studios

- The newspaper film genre popularized by films like 'The Front Page' (though later)

- Social reform dramas of the Progressive Era

- Mystery-comedy hybrids being developed in the late 1910s

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Mabel Normand features that blended comedy and drama

- Later newspaper comedies of the 1920s

- Films featuring strong female protagonists in journalism settings

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Floor Below is considered a lost film. No copies are known to exist in any film archive or private collection. The film was likely lost due to the common practice of film studios in the 1920s and 1930s of destroying silent film negatives to recover the silver content, combined with the highly flammable nature of nitrate film stock. The loss is particularly significant as it represents an important transitional work in Mabel Normand's career. Only production stills, promotional materials, and contemporary reviews survive to document the film's existence.