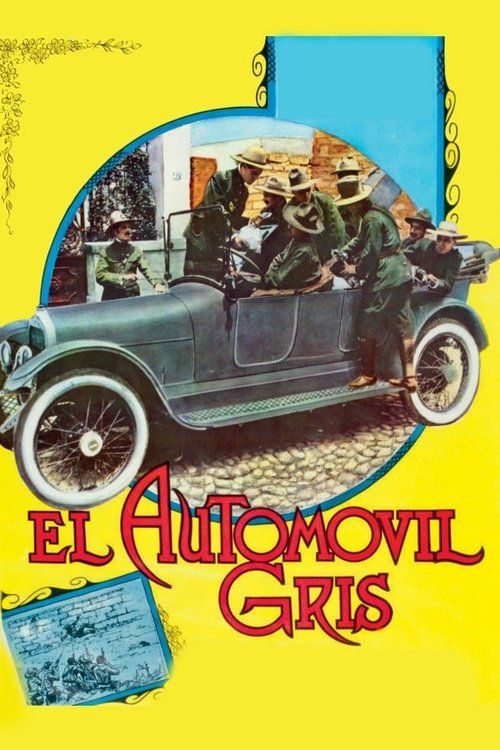

The Grey Automobile

"El crimen más audaz de la historia criminal de México"

Plot

Set in 1915 Mexico City during the turbulent revolutionary period, 'The Grey Automobile' follows the real-life crimes of a notorious gang that terrorized the city's elite society. Using their signature grey automobile as both transportation and weapon, the gang commits a series of daring robberies, kidnappings, and murders across the capital. Police Inspector Cabrera relentlessly pursues the criminals, methodically tracking their movements and gathering evidence through innovative investigative techniques. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation as Cabrera's investigation leads to the capture and imprisonment of the entire gang, bringing an end to their reign of terror. Based on actual events that shocked Mexican society, the film blends documentary-style realism with dramatic storytelling to create a gripping crime narrative.

About the Production

The film was notable for its use of actual locations where the real crimes took place, adding authenticity to the production. Director Enrique Rosas employed innovative techniques for the time, including location shooting and the use of real police officers as extras. The production faced challenges filming on the streets of Mexico City during a period of ongoing political instability following the Mexican Revolution. The grey automobile itself was a central prop and character in the film, meticulously chosen to match the description of the actual vehicle used by the real gang.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a crucial period in Mexican history, just four years after the most intense phase of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). Mexico City in 1915 was a city in transition, dealing with the aftermath of revolutionary upheaval while simultaneously modernizing. The real crimes depicted in the film shocked society because they represented a new type of criminality - organized, mobile, and targeting the elite. The automobile itself was a symbol of modernity and change, making its use in crimes particularly unsettling to the public. The film's release in 1919 came as Mexico was beginning to stabilize under President Venustiano Carranza, and audiences were ready to see stories about order being restored to society. The film also reflected the growing influence of American cinema techniques in Mexican film production, while maintaining distinctly Mexican themes and sensibilities.

Why This Film Matters

'The Grey Automobile' holds a unique place in Mexican cinema history as one of the earliest examples of the crime genre and as a film that blurred the lines between documentary and fiction. Its success demonstrated that Mexican audiences were hungry for stories that reflected their contemporary reality, rather than the historical dramas that had dominated early Mexican cinema. The film established several tropes that would become staples of Mexican crime films: the honorable police inspector, the sophisticated criminal gang, and the urban setting as a character in itself. It also marked one of the first times that recent, sensational news events were adapted into a narrative film, paving the way for future true crime adaptations. The film's preservation and restoration have made it an important document for understanding both early Mexican cinema and the social history of Mexico City in the 1910s.

Making Of

The production of 'The Grey Automobile' was groundbreaking for Mexican cinema in several ways. Director Enrique Rosas insisted on filming at the actual crime scenes, which required special permissions from the city authorities. The cast and crew often had to wait for real police operations to conclude before they could shoot. Joaquín Coss, who played Inspector Cabrera, spent weeks studying the real inspector's mannerisms and investigative methods. The film's most challenging sequence involved recreating a high-speed car chase through the streets of Mexico City, which was accomplished using multiple cameras mounted on different vehicles. The production team also faced the challenge of finding period-appropriate automobiles, eventually locating several models from 1915 that could be used in the filming. The gang's signature grey automobile was specially painted and modified to match descriptions from police reports of the actual vehicle used in the crimes.

Visual Style

The cinematography by (unknown - typical for films of this era) was innovative for its time, particularly in its use of location shooting throughout Mexico City. The film employed dynamic camera movement for the car chase sequences, which was technically challenging in 1919. The cinematographer made effective use of natural light and shadows to create a noir-like atmosphere despite being a silent film. The grey automobile itself became a visual motif, often framed ominously against the cityscape. The film also featured innovative point-of-view shots from inside the automobile during chase scenes, creating a sense of immediacy and danger. The visual style balanced documentary realism with dramatic composition, particularly in scenes of the gang's crimes and the police investigation.

Innovations

The film was technically ambitious for its time, particularly in its extensive use of location shooting throughout Mexico City. The car chase sequences were groundbreaking, requiring coordination between multiple camera units and vehicles. The film also employed innovative editing techniques for action scenes, using cross-cutting to build tension during the crimes and police pursuits. The production team developed special camera mounts for filming from moving automobiles, which was a significant technical challenge in 1919. The film's use of actual police officers and locations added a layer of authenticity that was rare in cinema of this era. The successful recreation of 1915 Mexico City in 1919 required meticulous attention to period detail in costumes, vehicles, and urban settings.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Grey Automobile' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have included a pianist or small orchestra playing popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music. For dramatic chase scenes, fast-paced music would have been played, while tense moments during the crimes would have been underscored with dissonant chords. The restored version that exists today is usually presented with newly composed scores or period-appropriate music when screened in theaters. Some modern presentations have used Mexican folk music and popular songs from the 1910s to maintain the film's cultural context.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, there are no spoken quotes, but intertitles included: 'The grey automobile strikes again!' / 'Justice will prevail!' / 'No one is above the law!' / 'The city lives in fear!'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic car chase through the streets of Mexico City, with the gang's grey automobile weaving through traffic while being pursued by police on horseback and in cars. The scene was filmed using multiple cameras and innovative techniques that created a sense of speed and danger rarely seen in films of this era.

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the real-life 'Grey Automobile Gang' that operated in Mexico City from 1915-1916

- Director Enrique Rosas was one of Mexico's pioneering filmmakers, and this was his most famous work

- The film was originally released in 12 parts as a serial, a common practice for longer films of the era

- Many of the police officers in the film were actual members of the Mexico City police force

- The real Inspector Cabrera, who captured the gang, served as a technical advisor on the film

- The film was considered lost for decades before a copy was discovered and restored in the 1950s

- It was one of the first Mexican films to gain international distribution, showing in several Latin American countries

- The gang's use of an automobile was particularly shocking in 1915, as cars were still rare in Mexico

- The film's success helped establish the crime genre in Mexican cinema

- Original promotional materials claimed the film showed '100% authentic scenes and locations'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its realism and thrilling narrative. The newspaper 'El Universal' called it 'the most exciting motion picture ever produced in Mexico' and particularly praised the performance of Joaquín Coss as Inspector Cabrera. Modern critics have recognized the film as a masterpiece of early Mexican cinema, noting its sophisticated use of location shooting and its blend of documentary and narrative techniques. Film historians have highlighted how the film captured the anxiety of a society transitioning from the chaos of revolution to a new modern era. The restored version has been featured in numerous film festivals and retrospectives of classic Mexican cinema, where it has been praised for its technical achievements and its historical value as a document of its time.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Mexican audiences upon its release, with reports of sold-out screenings in Mexico City for weeks. Audiences were particularly drawn to the fact that the story was based on recent, real events that many remembered from newspaper headlines. The serial format created anticipation and discussion among viewers, with people gathering to discuss each new episode. The film's success led to increased demand for more contemporary, urban stories in Mexican cinema. In later years, the film developed a cult following among cinema enthusiasts and historians, especially after its restoration. Modern audiences at revival screenings have responded positively to the film's energy and its fascinating window into early 20th century Mexico City.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- American gangster films of the 1910s

- French crime serials like 'Fantômas'

- Italian crime dramas

- German expressionist cinema (early influence)

- Contemporary newspaper crime reporting

This Film Influenced

- Later Mexican crime films of the 1930s-1940s

- Mexican film noir of the 1950s

- Modern Mexican true crime adaptations

- Gangster films across Latin America

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for several decades before a complete copy was discovered in the 1950s. It has since been restored by the Mexican Film Archive and is now considered one of the best-preserved examples of early Mexican cinema. The restored version has been screened internationally and is available for scholarly study. Some original footage remains missing, but the restored version contains the majority of the original film.