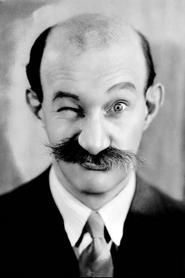

The Hoose-Gow

"Two Innocent Bystanders in the Wrong Penitentiary!"

Plot

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy arrive as new inmates at a state prison after being mistakenly identified as participants in a hold-up raid. Despite their protests that they were merely innocent bystanders watching the crime unfold, the prison authorities refuse to believe their story. The duo struggles to adapt to the rigid prison routine, causing chaos during laundry duty, rock breaking, and meal times with their characteristic incompetence and misunderstanding of rules. Their attempts to follow prison regulations only lead to more trouble, especially when they become involved in a fellow inmate's escape plan that goes disastrously wrong. The film culminates in a riot of comedic confusion that leaves Stan and Ollie in their familiar predicament of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Director

About the Production

This was one of Laurel and Hardy's earliest sound films, produced during Hollywood's challenging transition from silent to talkies. The production had to accommodate bulky early sound recording equipment, which limited camera movement and required actors to remain relatively stationary during dialogue scenes. The prison set was constructed specifically for this film but was reused in several subsequent Hal Roach productions. Director James Parrott, Hal Roach's brother-in-law, was experienced with the comedy duo and understood how to adapt their silent comedy timing to the new sound medium.

Historical Background

The Hoose-Gow was produced during a pivotal moment in American history and cinema. In 1929, Hollywood was undergoing a technological revolution with the rapid adoption of synchronized sound, fundamentally changing how films were made and experienced. Simultaneously, the nation was entering the Great Depression following the stock market crash in October 1929, creating widespread economic hardship and social anxiety. Prison-themed comedies like this one resonated with audiences dealing with financial constraints and feelings of powerlessness. The film reflects the era's fascination with institutional settings and the comedy of ordinary people struggling against bureaucratic systems. As one of the early sound comedies, it represents the entertainment industry's effort to provide escapist relief during difficult times while adapting to new technologies that would permanently transform cinema.

Why This Film Matters

The Hoose-Gow holds significant cultural importance as a pioneering example of how physical comedy successfully transitioned to the sound era. It demonstrated that visual humor could not only survive but thrive when combined with dialogue, influencing countless future comedy films. The movie helped establish Laurel and Hardy as masters of the sound comedy short, solidifying their status as one of cinema's most beloved comedy duos. Its prison setting became a template for future prison comedies, showing how institutional environments could serve as perfect backdrops for chaos and misunderstanding. The film contributed to the development of the buddy comedy genre, showcasing how contrasting personalities create enduring comedic chemistry. It also represents an important artifact of early sound cinema, preserving the techniques and approaches that filmmakers developed during this transitional period.

Making Of

The production of 'The Hoose-Gow' took place during one of the most challenging periods in Hollywood history - the transition from silent films to talkies. Early sound recording equipment was extremely cumbersome, requiring microphones to be hidden in props or suspended from the ceiling, which severely limited the actors' mobility. Laurel and Hardy, who had built their reputation on dynamic physical comedy, had to adapt their style to work within these technical constraints. Director James Parrott worked closely with the sound technicians to find creative solutions that would preserve the duo's comedic timing while accommodating the new technology. The prison set was designed with sound recording in mind, featuring hard surfaces that helped capture dialogue clearly while providing ample space for physical comedy. The filming process required multiple takes to achieve both clear audio and perfect comedic timing, making the production more time-consuming and expensive than their silent shorts. Despite these challenges, the film successfully demonstrated that Laurel and Hardy's comedy could thrive in the sound era.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens reflects the technical constraints and creative solutions of early sound filming. Camera movements were significantly limited due to the need to keep actors close to hidden microphones, resulting in more static compositions than typical of Laurel and Hardy's silent films. Stevens compensated for these limitations through creative framing that emphasized the duo's facial expressions and physical comedy. The lighting had to be carefully arranged to accommodate both visual clarity and the requirements of early sound recording, with brighter illumination than usual to ensure good audio pickup. Despite these technical restrictions, the cinematography effectively captures the chaotic energy of the prison setting and the comedic timing of the performances. The film's visual style represents a transitional aesthetic between the fluid camera work of silent comedies and the more dialogue-focused approach of early sound films.

Innovations

The Hoose-Gow represents an important technical achievement in early sound comedy, demonstrating how physical humor could be preserved and enhanced through audio technology. The production team developed innovative techniques to capture both clear dialogue and dynamic physical comedy within the constraints of early sound equipment. They pioneered methods for microphone placement that allowed for more natural actor movement while maintaining audio quality. The film contributed to the development of comedic timing for sound, showing how pauses and verbal delivery could enhance visual gags. The successful integration of sound effects with physical comedy created a new dimension of humor that wasn't possible in silent films. These technical innovations influenced countless subsequent comedy productions and helped establish the language of sound comedy that would dominate Hollywood for decades.

Music

The film features a musical score typical of Hal Roach productions, with light, whimsical accompaniment that enhances the visual humor without overwhelming it. The music was likely composed by Leroy Shield, who created many of the memorable themes for Laurel and Hardy films. Sound effects were carefully synchronized with the physical comedy, creating a more immersive experience than silent films could provide. The dialogue recording, while primitive by modern standards, was clear enough to convey the verbal humor and character interactions that were becoming increasingly important in comedy films. The film's audio design helped establish the template for sound comedy, balancing music, dialogue, and effects to maximize comedic impact. The sound quality represents the technological limitations of 1929 but successfully captures the charm and humor of Laurel and Hardy's performances.

Famous Quotes

We were just watching! That's all!

Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!

I didn't do it! He didn't do it! We didn't do it!

You can't do this to us! We're innocent!

Prison? But we were just standing there!

Memorable Scenes

- The opening arrival sequence where Stan and Ollie try to explain their innocence to the prison warden, becoming increasingly flustered as their explanations only make them sound more guilty

- The chaotic laundry room scene where the duo attempts to follow prison rules but creates a whirlwind of soapsuds and tangled clothing

- The rock-breaking sequence showing their complete incompetence at manual labor, with Stan managing to break everything but the rocks

- The dinner hall scene where they struggle with prison food and regulations, causing a chain reaction of comedic disasters

- The failed escape attempt that goes spectacularly wrong, involving a makeshift ladder and a series of unfortunate misunderstandings

Did You Know?

- The title 'Hoose-Gow' is American slang derived from the Chinese phrase 'huzhao,' meaning prison or penitentiary

- This was one of Laurel and Hardy's first sound films, made just two years after their first official pairing as a comedy team

- Tiny Sandford, who played the prison guard, appeared in over 20 Laurel and Hardy films and worked with Charlie Chaplin in 'Modern Times'

- The prison set was so well-constructed that it was reused in multiple Hal Roach productions throughout the 1930s

- The film was originally released as part of MGM's prestigious 'All Talking' series, highlighting the novelty of synchronized sound

- Some outdoor scenes were filmed indoors on soundstages to accommodate early sound recording equipment and reduce background noise

- The title was sometimes misspelled as 'The Hoose-Go' in contemporary advertisements and theater listings

- This film helped establish the prison comedy as a recurring subgenre in Hollywood, leading to numerous similar films

- The movie was produced during the stock market crash of 1929, making its themes of institutional confinement particularly resonant with audiences

- Laurel and Hardy performed their own stunts in the physical comedy sequences, including the chaotic laundry room scene

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Hoose-Gow' for successfully maintaining Laurel and Hardy's comedic appeal in their new sound format. Variety magazine noted that the duo 'lost none of their timing or humor' in the transition to talking pictures, while The Film Daily called it 'a laugh riot from start to finish.' Critics particularly appreciated how the film balanced dialogue with physical comedy, something many comedians struggled with during this period. Modern critics view the film as an exemplary early sound comedy that preserved the essence of silent-era humor while embracing new possibilities. Film historian Leonard Maltin has cited it as 'one of the team's best early talkies,' while the British Film Institute includes it in their list of significant comedy shorts. The film is often studied in film schools as an example of successful adaptation to new technology.

What Audiences Thought

The Hoose-Gow was enthusiastically received by audiences in 1929, who were eager to see their favorite comedy stars embrace the new sound technology. Theater owners reported strong attendance and positive audience reactions, with viewers laughing at both the visual gags and newly incorporated verbal exchanges. The film's success helped establish Laurel and Hardy as bankable stars in the sound era, proving their appeal transcended the silent film format. Contemporary audiences continue to enjoy the film through home video releases and classic film screenings, with many considering it among the duo's funniest shorts. The movie maintains a 7.8/10 rating on IMDb and is frequently praised in online forums by classic comedy enthusiasts. Its enduring popularity demonstrates how Laurel and Hardy's humor transcends generational and technological divides.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Music hall traditions

- Chaplin's prison sequences in 'Modern Times'

- Buster Keaton's physical comedy style

- Earlier silent prison comedies

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedy style

This Film Influenced

- Pardon Us (1931) - Laurel and Hardy's feature-length prison comedy

- Various Three Stooges prison shorts

- Later prison comedies like 'Stir Crazy'

- Television sitcom prison episodes

- Modern buddy comedy films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Hoose-Gow has been successfully preserved and is available in multiple formats. The original nitrate film elements have been transferred to safety film and digital formats as part of various Laurel and Hardy restoration projects. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition with complete versions available for viewing. It has been included in several DVD and Blu-ray collections, including 'The Laurel & Hardy Collection' and 'Hal Roach's Comedy All-Stars.' The Library of Congress maintains preservation copies, and the film has been screened at numerous classic film festivals and retrospectives.