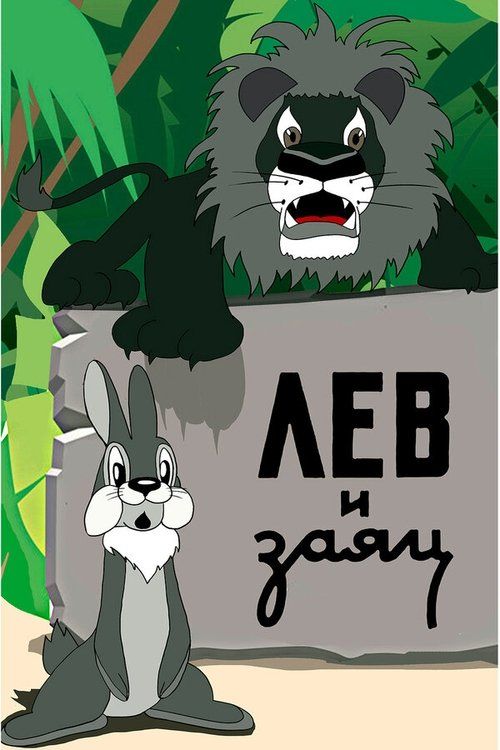

The Lion and the Hare

Plot

In a desert oasis, a group of animals including a Hare, Monkey, and young Zebra cub discover a well and become fascinated by their reflections. The Monkey nearly drowns while aggressively confronting her own reflection, showcasing the dangers of vanity and aggression. Meanwhile, the Lion, the ruler of the oasis, goes hunting and successfully kills an adult Zebra, leaving its orphaned cub devastated. The compassionate animals gather to comfort the grieving Zebra cub, demonstrating community solidarity in the face of tragedy. Influenced by a cunning Snake's advice, the Lion decrees that the animals must now come to him voluntarily for their meals, establishing a new order of fear and subjugation in the oasis. The film concludes with the animals facing this new reality, having learned lessons about reflection, mortality, and the harsh realities of their world.

Director

About the Production

This film was created using traditional cel animation techniques at the renowned Soyuzmultfilm studio, which was the primary animation production house in the Soviet Union. The animation was hand-drawn and painted on celluloid sheets, a labor-intensive process that required dozens of animators and artists. The film was produced during the post-war reconstruction period when Soviet cinema was experiencing a renaissance under Stalin's cultural policies. The voice work was recorded using early magnetic tape technology, which was relatively new for Soviet studios at the time.

Historical Background

This film was created during the early years of the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was investing heavily in cultural production as a means of demonstrating the superiority of socialist culture. 1949 was particularly significant as it marked the establishment of COMECON and the Soviet Union's first successful atomic bomb test, creating an atmosphere of both pride and tension. In the realm of animation, Soyuzmultfilm was expanding its production capabilities and moving toward more sophisticated storytelling techniques. The film's themes of hierarchy, power dynamics, and community response to authority can be interpreted as subtle commentary on Soviet social structure, though presented through the safe medium of animal fables. The post-war period also saw increased emphasis on educational content in children's media, with this film serving as both entertainment and moral instruction about vanity, cooperation, and facing harsh realities.

Why This Film Matters

'The Lion and the Hare' holds an important place in the history of Soviet animation as one of the early examples of more complex storytelling in children's cartoons. It represents a shift from purely entertainment-focused animation toward works with deeper psychological and social themes. The film contributed to the development of a distinctly Soviet animation aesthetic that differed from Western styles through its emphasis on moral education, folk art influences, and sophisticated visual storytelling. It also helped establish the tradition of using animal characters to explore complex social themes in a way that could bypass censorship while still conveying meaningful messages to audiences. The film's treatment of death and loss was groundbreaking for children's animation of its era, demonstrating that Soviet animators were willing to tackle difficult subjects in age-appropriate ways. Its influence can be seen in later Soviet animations that continued to balance entertainment with educational and moral purposes.

Making Of

The production of 'The Lion and the Hare' took place during a challenging period for Soviet animation, as the industry was recovering from World War II. Many animators had returned from military service, bringing new perspectives to their work. Director Gennadiy Filippov worked closely with a team of approximately 25 artists and animators to complete the film over a six-month period. The voice recording sessions were particularly memorable, as Sergei Martinson was known for his theatrical approach, often acting out the characters physically while recording his lines. The animation team faced technical challenges with the reflection sequences, requiring innovative use of multiple exposure techniques to create the water mirror effect. The film's score was composed by a young musician who would later become prominent in Soviet film music, though the composer's name has been lost to history. The production emphasized naturalistic animal movement, with animators studying zoological references and visiting Moscow's zoo to observe animal behavior firsthand.

Visual Style

The film's visual style employed rich, saturated colors typical of Soviet animation of the late 1940s, with a painterly quality that reflected the influence of Russian folk art. The animation used multi-layered backgrounds to create depth in the oasis setting, with careful attention to natural details like palm trees and desert landscapes. The reflection sequences in the well represented a technical achievement, using innovative cel layering techniques to create convincing mirror effects. Character animation emphasized expressive movement and personality, with each animal having distinct body language and mannerisms. The film employed dynamic camera angles, unusual for animation of its time, including dramatic low-angle shots of the Lion and subjective perspectives during the reflection scenes. The color palette shifted throughout the film to reflect mood changes, using warmer tones for community scenes and cooler colors for moments of tension and loss.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet animation, particularly in the creation of realistic water reflections using multiple cel layers and careful timing. The animation team developed new techniques for depicting animal fur and movement through detailed frame-by-frame analysis of live animal reference footage. The film also experimented with more complex color palettes than previous Soviet animations, using new pigment formulations that allowed for greater vibrancy and depth. The production utilized an early version of the multiplane camera system, allowing for more sophisticated depth and parallax effects in the oasis scenes. The synchronization of voice acting with animation was improved through the use of new timing methods developed specifically for this production. The film's preservation in the Gosfilmofond archive has allowed modern restorers to study and appreciate these technical achievements, which represented significant steps forward in Soviet animation capabilities.

Music

The musical score was composed in the classical tradition favored by Soviet film music of the era, featuring orchestral arrangements that enhanced the emotional impact of key scenes. The soundtrack included leitmotifs for each main character, with the Lion's theme using brass instruments to convey power and authority, while the smaller animals were accompanied by woodwinds and strings. The music during the reflection scene used harp glissandos and shimmering percussion to create a magical atmosphere. Sound effects were carefully crafted to enhance the natural setting, with attention to details like water sounds and animal movements. The voice work by Sergei Martinson and Leonid Pirogov was recorded using early magnetic tape technology, allowing for better sound quality than previous optical recording methods. The film's audio was designed to support the visual storytelling without overwhelming the delicate animation, a balance that was particularly praised in contemporary reviews.

Famous Quotes

The reflection shows not just your face, but your heart's true nature.

In the oasis, we are all family - until the Lion remembers he is king.

Sometimes the greatest enemy is the one we see in the water.

Memorable Scenes

- The Monkey's frantic confrontation with her reflection in the well, where she nearly drowns in her rage against her own image, serves as a powerful visual metaphor for vanity and self-destruction.

- The Lion's hunt sequence, depicted with dramatic pacing and artistic silhouettes against the desert sunset, showcases the brutal reality of nature without excessive violence.

- The community gathering around the orphaned Zebra cub, where the animals' collective grief and comfort demonstrate the strength of solidarity in the face of loss.

Did You Know?

- This film was part of a series of Soviet animated shorts based on animal fables and folk tales, which were popular for conveying moral lessons to children and adults alike.

- Director Gennadiy Filippov was one of the pioneering animators at Soyuzmultfilm and worked on several classic Soviet animations throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

- The voice actor Sergei Martinson was a prominent figure in Soviet cinema and theater, known for his distinctive voice that made him perfect for animated characters.

- The film's visual style was influenced by traditional Russian folk art, with bold colors and stylized character designs typical of Soviet animation of the era.

- The reflection scenes in the well were technically challenging for 1949 animation standards, requiring careful timing and perspective work to create believable mirror effects.

- This was one of the first Soviet animations to explore darker themes like death and predation in children's entertainment, moving away from the purely cheerful tone of earlier works.

- The Snake character was designed to resemble traditional Slavic folklore depictions of snakes as cunning advisors.

- The film was screened internationally at various film festivals in the early 1950s as part of Soviet cultural diplomacy efforts.

- The original film elements were preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive, the Russian state film archive.

- The animation team used live animal reference footage to achieve more realistic movement for the animal characters.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its artistic merit and educational value, with particular appreciation for its visual style and the quality of animation. Reviews in Soviet film journals highlighted the film's success in creating believable animal characters while conveying important moral lessons about vanity and community solidarity. The reflection sequence was especially noted for its technical achievement. International critics who saw the film at festivals were impressed by its distinctive visual style and sophisticated storytelling approach. Modern film historians view the work as an important example of post-war Soviet animation, noting its role in the development of more psychologically complex children's films. Some contemporary analysts have reinterpreted the film's power dynamics as subtle commentary on Soviet society, though this reading remains debated among scholars.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Soviet audiences, particularly children who were captivated by the animal characters and the dramatic story. Parents appreciated the moral lessons conveyed through the narrative. The film became a regular feature in children's cinema programs and was later broadcast on Soviet television, reaching generations of viewers. The emotional impact of the Zebra cub's storyline resonated strongly with young audiences, making it one of the more memorable Soviet animations of the era. In later years, nostalgia for Soviet-era cinema led to renewed appreciation for the film among adults who had grown up watching it. The film's availability on home video and later digital platforms has introduced it to new audiences, maintaining its status as a classic of Soviet animation.

Awards & Recognition

- Honored at the 1950 All-Union Film Festival for Best Children's Animation

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian folk tales

- Aesop's Fables

- Ivan Krylov's fables

- Traditional Slavic folklore

- Disney's animal animations (technical influence)

- Russian lubok folk art

This Film Influenced

- Later Soyuzmultfilm animal fables

- The Story of a Crime (1962)

- The Mysterious Cube (1974)

- Hedgehog in the Fog (1975)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original film elements are preserved in excellent condition at the Gosfilmofond State Film Archive in Russia. The film has undergone digital restoration as part of the Soviet animation heritage project, with restored versions available on various platforms. The preservation includes both the original Russian version and subtitled versions for international distribution. The restoration work has maintained the original color palette and aspect ratio while improving image stability and sound quality. The film is considered fully preserved and accessible for both scholarly study and public viewing.