The Photographical Congress Arrives in Lyon

Plot

This historic 1895 short documentary captures a significant moment as members of a photographic congress disembark from a riverboat in Lyon, France. The film shows dozens of photographers carrying their equipment and cases as they carefully make their way down the gangplank, creating a fascinating meta-cinematic moment where photographers themselves become the subject of a new photographic medium. The composition demonstrates Louis Lumière's keen eye for framing and movement, capturing the organized chaos of the crowd as they navigate the narrow walkway. The congress members, dressed in formal 19th-century attire, represent the convergence of traditional photography and the revolutionary new technology of cinema that would soon transform visual media forever.

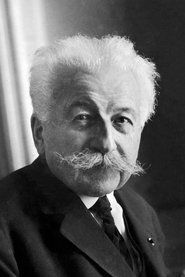

Director

About the Production

Filmed using the Lumière Cinématographe, which served as both camera, developer, and projector. The camera was hand-cranked at approximately 16 frames per second. The film was shot in a single continuous take, demonstrating the Lumière brothers' preference for capturing real events rather than staged scenes. The location was chosen specifically because the Lumière factory was nearby in Lyon's Monplaisir district.

Historical Background

This film was created during the revolutionary year of 1895, when the Lumière brothers were perfecting and demonstrating their Cinématographe invention. France was experiencing the Belle Époque, a period of cultural and technological innovation. The photographic industry was well-established, with Lyon being a major center for photographic manufacturing and innovation. The congress depicted represents the peak of traditional photography just as cinema was about to transform visual culture forever. This film captures a pivotal moment when two technologies overlapped - the mature art of photography and the nascent medium of motion pictures. The screening of this film on December 28, 1895, at the Grand Café in Paris is widely considered the birth of commercial cinema, marking the transition from optical toys and scientific curiosities to a new art form and industry.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest surviving motion pictures and a prime example of the Lumière brothers' 'actualité' style. It represents the birth of documentary filmmaking, capturing real events as they unfolded. The meta-narrative of photographers being filmed created a profound statement about the evolution of visual technology. This film helped establish the fundamental language of cinema, including framing, composition, and the documentation of real events. It influenced generations of documentary filmmakers and remains a crucial reference point for understanding cinema's origins. The film's preservation and continued study demonstrate how cinema has always been fascinated with its own creators and processes.

Making Of

The filming was conducted by Louis Lumière himself, who personally operated the Cinématographe. The camera was positioned on a tripod at a carefully chosen angle to capture both the gangplank and the riverboat, demonstrating Louis's sophisticated understanding of composition despite the medium's infancy. The photographers were unaware they were being filmed for posterity, as they were attending what they believed to be a conventional photographic congress. The Lumière factory workers likely assisted with the setup, as the company operated with a small, dedicated team. The film was processed on-site using the Lumière brothers' own developing process, which was revolutionary for its time in allowing rapid processing of motion picture footage.

Visual Style

The cinematography demonstrates Louis Lumière's sophisticated understanding of composition despite the medium's infancy. The camera was positioned to create a diagonal composition with the gangplank, adding visual interest to the scene. The framing captures both the vertical movement of the photographers descending and the horizontal expanse of the riverboat. The single continuous take creates a sense of real-time observation, emphasizing the documentary nature of the work. The lighting is entirely natural, utilizing available daylight, which creates authentic shadows and highlights that enhance the three-dimensional quality of the image.

Innovations

This film showcased the revolutionary Cinématographe device, which was lighter and more portable than competing cameras like Edison's Kinetograph. The film demonstrated the practical application of 35mm film with perforations, a format that would become the industry standard. The ability to capture outdoor scenes with natural lighting was groundbreaking, as was the camera's relatively high image quality and frame rate consistency. The film also demonstrated the Lumière process's rapid development capabilities, allowing footage to be processed and shown relatively quickly after shooting.

Music

As a silent film from 1895, this work had no synchronized soundtrack. During early screenings, the Lumière brothers sometimes employed live musical accompaniment, typically a pianist playing popular tunes of the era. Some modern presentations have added period-appropriate musical scores, but the original viewing experience would have been silent except for the mechanical noise of the projector and audience reactions.

Memorable Scenes

- The entire film consists of one memorable scene: dozens of formally dressed 19th-century photographers carefully descending a gangplank from a riverboat, carrying their photographic equipment and cases, creating a remarkable historical document of both a specific event and the transition between photographic technologies.

Did You Know?

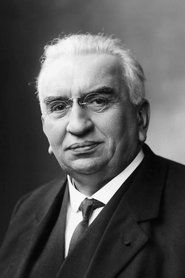

- This film features a rare appearance by Auguste Lumière himself, who can be seen among the photographers disembarking

- The congress depicted was likely the Congrès International de Photographie held in Lyon in August 1895

- This is one of the earliest examples of a 'meta' film - a film about photographers, created by inventors of photography's successor technology

- The film was shot on 35mm film stock, a format that would become the industry standard for over a century

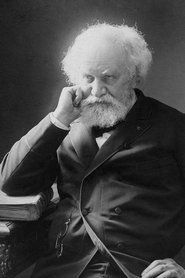

- Among the disembarking photographers is Pierre Jules César Janssen, a prominent French astronomer who developed early photographic techniques

- The Lumière brothers showed this film at their first public screening, which featured 10 films total and is considered the birth of commercial cinema

- The riverboat shown was likely a vessel on the Rhône River, which flows through Lyon

- This film demonstrates the Lumière philosophy of 'actualities' - capturing real life rather than creating fictional narratives

- The film's title reflects the 19th-century convention of extremely descriptive, literal titles for moving pictures

- Only a few copies of this film survive today, preserved at the Lumière Institute in Lyon and other film archives worldwide

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1895 were amazed by the film's realism and clarity. The Paris newspaper Le Figaro described the Lumière screening as 'marvelous' and noted how the moving images seemed to bring photographs to life. Critics particularly praised the film's clarity and the natural movement of the subjects. Modern critics and film historians consider this a seminal work of early cinema, praising its composition, historical importance, and the irony of its subject matter. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema as an example of the Lumière aesthetic and the birth of documentary filmmaking.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences at the first public screenings were reportedly astonished by the lifelike quality of the images. Many viewers reportedly ducked or moved aside when the photographers appeared to walk toward them, demonstrating the unprecedented realism of the Lumière films. The film was particularly popular with photographers and technical enthusiasts who appreciated the documentation of their profession. Contemporary audiences at screenings of this film today respond with fascination to this glimpse of 19th-century life and the meta-commentary on visual media's evolution.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography

- Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope films

- Traditional photography

- Documentary tradition of recording events

This Film Influenced

- Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895)

- Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895)

- The Sprinkler Sprinkled (1895)

- Early actuality films by other pioneers

- Modern documentary films about photographers

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved at the Lumière Institute in Lyon, France, and in various international film archives including the Cinémathèque Française. Multiple copies exist, though some show varying degrees of deterioration. The film has been digitally restored by the Lumière Institute as part of their comprehensive restoration of the Lumière brothers' works.