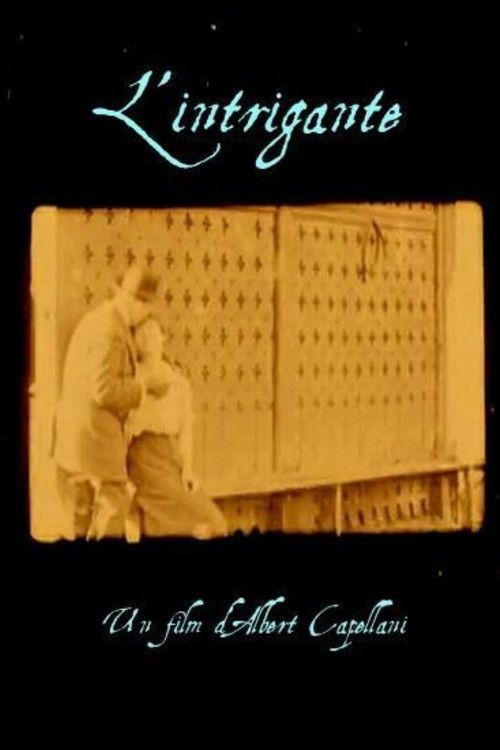

The Schemer

"The lens that never lies catches the bride who always does!"

Plot

A wealthy socialite and bride-to-be engages in a clandestine affair, believing her status and cleverness will shield her from discovery. Unbeknownst to her, a private investigator or a suspicious party utilizes the burgeoning technology of the era—a hidden camera—to document her infidelities. The film reaches its climax when the photographic evidence is developed and presented, leading to a public confrontation that shatters her carefully constructed facade. The narrative serves as a cautionary tale about the permanence of the photographic record and the inevitable downfall of those who attempt to deceive their social circles.

Director

About the Production

Directed by the prolific Albert Capellani, who was a pioneer in the 'Film d'Art' movement, this production reflects the transition of French cinema toward more complex, multi-scene narratives. The film was produced under the S.C.A.G.L. banner, a subsidiary of Pathé dedicated to adapting literary and theatrical works for the screen with high production values. The use of a camera as a central plot device (a 'film within a film' concept) was a sophisticated meta-narrative choice for 1911, highlighting the public's fascination with new surveillance technologies.

Historical Background

In 1911, France was the global center of the film industry, and the 'Belle Époque' was reaching its cultural zenith. This era saw a shift in cinema from 'attractions' (simple visual gags) to 'narrative' (complex stories), driven by directors like Capellani. Socially, the film reflects contemporary anxieties regarding the changing role of women and the increasing intrusion of technology into private life. The Dreyfus Affair, which had concluded only a few years prior, had also sensitized the French public to the power of forged or hidden evidence in social and legal scandals.

Why This Film Matters

The film is significant for its early portrayal of photography as a tool for social justice and moral policing. It contributed to the 'Cinema of Transgression' where the camera acts as a voyeur, a theme that would later be explored by masters like Alfred Hitchcock. By casting established stage actors like Catherine Fonteney and Georges Tréville, the film helped elevate the status of cinema from a fairground attraction to a legitimate art form suitable for the middle and upper classes.

Making Of

During the production of 'The Schemer', Albert Capellani focused on naturalistic acting, a departure from the exaggerated pantomime common in earlier silent shorts. The set design was handled by Pathé's dedicated artisans, who created lavish bourgeois interiors to emphasize the high stakes of the bride's social fall. The technical challenge involved filming the 'photographic evidence' in a way that was legible to the audience, necessitating close-up shots of the developed prints—a technique still in its infancy. Capellani's direction ensured that the pacing built tension toward the final reveal of the photographs.

Visual Style

The cinematography is characterized by static, wide-angle shots typical of the era, but with a sophisticated use of deep space. Capellani and his cameraman utilized the 'tableau' style, where action is staged in layers within the frame. The lighting is mostly flat and naturalistic, typical of studio filming in the early 1910s, but the framing of the 'photographs' within the scene was a notable attempt at directing the viewer's gaze.

Innovations

The film is a notable early example of using a 'prop-as-plot-device,' where the camera itself becomes a character in the narrative. It also demonstrates an early understanding of 'insert shots'—though often handled through staging rather than editing—to show the audience the contents of the incriminating photographs.

Music

As a silent film, there was no recorded soundtrack. Original screenings would have been accompanied by a live pianist or a small orchestra playing stock dramatic music from the Pathé repertoire, likely emphasizing the suspenseful moments of the 'scheming' and the final confrontation.

Memorable Scenes

- The 'Darkroom Reveal': A tense scene where the protagonist or investigator develops the film, and the image of the cheating bride slowly appears in the chemical bath.

- The Wedding Confrontation: The climactic moment where the photographs are produced in front of the wedding party, leading to the bride's public disgrace.

Did You Know?

- The film is also known by its original French title, 'L'Intrigante'.

- Director Albert Capellani was the brother of actor Paul Capellani, who often appeared in his films.

- The film is cited by historians as an early example of the 'detective' or 'surveillance' subgenre in silent cinema.

- At the time of its release, Pathé Frères was the largest film production and distribution company in the world.

- The cast included Georges Tréville, who would later become famous for playing Sherlock Holmes in a series of French-British films in 1912.

- Catherine Fonteney, who played the lead, was a respected stage actress from the Comédie-Française.

- The film utilizes a 'watch camera' or 'detective camera,' which were popular novelty items in the early 1900s.

- It was released during a period when Albert Capellani was transitioning from short trick films to epic literary adaptations like 'Les Misérables' (1913).

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade journals like 'The Moving Picture World' praised the film for its clear narrative and the 'moral lesson' it provided. Modern film historians view it as a key work in Albert Capellani's filmography, illustrating his ability to weave technical gadgets into dramatic storytelling. It is often studied in the context of 'early cinema' for its use of props to drive the plot forward without the need for extensive intertitles.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1911 were reportedly enthralled by the 'detective' elements of the plot, as the use of hidden cameras was a popular trope in contemporary pulp fiction. The film's short runtime and dramatic 'reveal' made it a staple of nickelodeons and early cinema houses across Europe and North America. Its success helped solidify Pathé's reputation for producing high-quality 'drames de mœurs' (dramas of manners).

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The plays of Alexandre Dumas fils

- Contemporary French detective novels

- The 'Film d'Art' movement

This Film Influenced

- Rear Window (1954)

- Blow-Up (1966)

- The Conversation (1974)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various archives, including the Pathé-Gaumont Archives and the Cinémathèque Française. It has been featured in retrospectives of Albert Capellani's work.