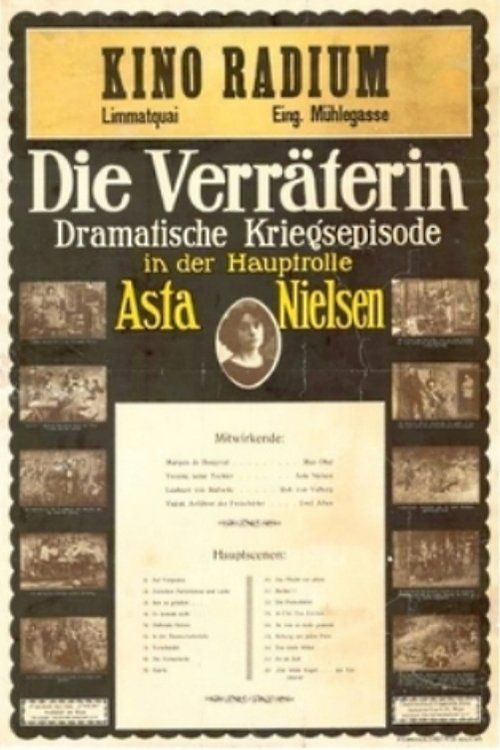

The Traitress

Plot

A young woman becomes infatuated with a military officer who coldly rejects her romantic advances. Consumed by spite and vengeance, she betrays the location of his regiment to enemy forces, leading to his capture. Overcome with guilt and remorse when she realizes the consequences of her actions, she embarks on a desperate mission to rescue the man she both loves and has wronged. The film follows her emotional transformation from vengeful traitor to self-sacrificing heroine as she risks everything to atone for her betrayal. Set against the backdrop of military conflict, the story explores complex themes of unrequited love, moral responsibility, and the possibility of redemption through self-sacrifice.

Director

About the Production

This film was part of the remarkable output from Nordisk Film during Denmark's golden age of cinema (1910-1914). The production utilized the sophisticated studio facilities that Nordisk had developed in Valby, Copenhagen. Director Urban Gad and star Asta Nielsen had already established their successful creative partnership, having made several films together that gained international acclaim. The film was likely shot quickly, as was common in this era of rapid film production, with minimal rehearsal and emphasis on spontaneous performance. The military setting would have required period costumes and props, reflecting the attention to detail that characterized Danish productions of this period.

Historical Background

1911 marked the height of Denmark's golden age of cinema, when the small Scandinavian nation was producing some of the world's most sophisticated and commercially successful films. This period saw Danish cinema competing strongly with French and American productions in international markets. The film industry was rapidly evolving from short novelty pieces to longer, more complex narrative features. Copenhagen had become a major center of film production, with Nordisk Film leading the way in technical innovation and artistic quality. The film's military themes reflected the growing tensions in Europe that would eventually lead to World War I, though audiences in 1911 could not yet foresee the coming conflict. This was also a period of significant social change, with evolving attitudes toward women's roles and sexuality reflected in the more complex female characters appearing in Danish cinema. The international success of films like 'The Traitress' helped establish the global nature of the film industry and the concept of the movie star as an international cultural phenomenon.

Why This Film Matters

The film represents a crucial milestone in the development of narrative cinema and the emergence of the psychological drama as a legitimate art form. Asta Nielsen's performance helped establish the potential for subtle, emotionally complex acting in silent film, moving beyond the broad gestures and theatricality that characterized much early cinema. The film's exploration of female moral complexity and agency was relatively progressive for its time, reflecting the sophisticated storytelling that made Danish cinema internationally respected. The collaboration between Gad and Nielsen contributed significantly to the development of film language, particularly in the use of close-ups and nuanced performance to convey psychological states. The international success of the film and others like it helped establish Denmark as a major force in early global cinema and demonstrated the commercial viability of feature-length dramatic films. The film's themes of betrayal, guilt, and redemption resonated with audiences across cultural boundaries, helping establish the universal emotional appeal of cinema as an art form.

Making Of

The collaboration between Urban Gad and Asta Nielsen represented one of the most significant creative partnerships in early cinema history. Gad, who had written the screenplay specifically for Nielsen, tailored the complex role to showcase her unique acting abilities and screen presence. The production took place during a remarkably productive period for both artists, when they were creating up to six films per year. Nielsen's naturalistic acting style, which emphasized psychological truth over theatrical convention, was revolutionary for the time and required Gad to adapt his directing techniques accordingly. The film's military setting allowed for elaborate costumes and props that showcased Nordisk Film's production capabilities. Behind the scenes, the cast and crew worked with the primitive technology of the era, including hand-cranked cameras that required constant attention and natural lighting that limited shooting hours. The emotional intensity of the story demanded significant preparation from Nielsen, who was known for her meticulous approach to character development and her ability to maintain emotional consistency across multiple takes.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed the sophisticated techniques that characterized Danish cinema during this period, including careful composition and the innovative use of close-ups to emphasize emotional moments. The visual style utilized dramatic lighting to enhance the psychological content of scenes, particularly in moments of moral crisis and emotional transformation. The film was shot on black and white film stock using hand-cranked cameras that required skilled operators to maintain consistent exposure and movement. The cinematography likely employed the relatively new technique of using multiple camera setups to capture different angles of the same scene, allowing for more dynamic visual storytelling. The visual composition would have emphasized the psychological states of the characters through framing and camera positioning, reflecting Urban Gad's sophisticated understanding of film as a visual medium. The film's visual language, while technically simple by modern standards, was artistically advanced for its time and contributed significantly to the emotional impact of the narrative.

Innovations

While the film did not introduce major technical innovations, it represented the state of the art in 1911 filmmaking and demonstrated the sophisticated production capabilities of Nordisk Film. The production utilized the most advanced camera and lighting equipment available at the time, including artificial lighting systems that allowed for greater control over visual atmosphere. The film's narrative complexity and psychological depth demonstrated the evolving capabilities of cinema as a storytelling medium, moving beyond simple action or spectacle to explore human emotions and moral dilemmas. The collaboration between Gad and Nielsen helped develop techniques for conveying complex psychological states through visual performance, which was a significant achievement in early cinema. The film's production values, including its costumes, props, and sets, reflected the high standards of Danish cinema during this period and contributed to the film's international success. The technical execution of the film supported its artistic ambitions, demonstrating how cinematic technology could be used to serve sophisticated narrative and emotional content.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Traitress' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings, with the specific music varying by venue and region. Large urban theaters might have employed full orchestras playing specially compiled scores that combined classical pieces with original compositions, while smaller venues would have used piano or organ accompaniment. The music would have been carefully chosen to match the film's dramatic tone and emotional arc, with different themes representing the various psychological states of the characters. The score would have emphasized key moments of betrayal, remorse, and attempted redemption through appropriate musical selections. Some theaters might have used cue sheets provided by the distributor to ensure consistent musical accompaniment across different venues. The live musical performance was an integral part of the cinematic experience in 1911, with the quality of the musical accompaniment often being as important to audiences as the visual content of the film itself.

Did You Know?

- The original Danish title was 'Den Forræderske,' which translates directly to 'The Traitor Woman' or 'The Female Traitor'

- Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad married in 1912, the year after this film was released, making this one of their final collaborations before marriage

- Nordisk Film, the production company, was founded in 1906 and is still operating today, making it the world's oldest film studio still in production

- This film was released during the peak of Danish cinema's international influence, before World War I disrupted European film production

- Asta Nielsen was reportedly paid 1,000 marks per week for her German productions, making her one of the highest-paid actresses of the silent era

- The film was likely distributed internationally with translated intertitles, helping establish Nielsen as an international star

- Urban Gad was one of the first directors to recognize and utilize Asta Nielsen's unique screen presence and acting style

- Many early Danish films were destroyed in a 1928 fire at the Nordisk Film studios, making surviving prints extremely rare

- The film's theme of female moral complexity was relatively progressive for its time, reflecting the sophisticated storytelling of Danish cinema

- Contemporary audiences were particularly drawn to Nielsen's ability to convey complex emotions through subtle facial expressions rather than theatrical gestures

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's dramatic intensity and Asta Nielsen's powerful performance, with many reviewers noting her ability to convey complex emotions through subtle facial expressions and body language. The psychological depth and moral sophistication of the story were highlighted as distinguishing features from the more straightforward melodramas common in the period. Critics particularly appreciated the film's exploration of female psychology and its refusal to present a simple villain or heroine, instead offering a complex character capable of both betrayal and redemption. The film's technical qualities, including its cinematography and production design, were also noted as evidence of Danish cinema's high standards. Modern film historians recognize 'The Traitress' as an important example of early narrative cinema's artistic ambitions and as a significant work in Asta Nielsen's early career that helped establish her international reputation as one of cinema's first true stars.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enthusiastically received by audiences across Europe and in other international markets where it was distributed. Asta Nielsen's growing international star power guaranteed strong attendance, with many viewers specifically seeking out her latest performance. The dramatic story of betrayal and redemption appealed to early cinema audiences who were developing an appetite for emotionally engaging narratives with psychological complexity. Audience reactions were particularly strong to Nielsen's performance, with many viewers reporting being moved by her portrayal of the character's emotional journey from vengeful spite to remorseful redemption. The film's success in multiple countries demonstrated the growing global appeal of cinema as a universal language of emotion and storytelling. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film generated significant discussion about its moral implications and its portrayal of a complex female character, indicating that it engaged audiences on an intellectual as well as emotional level.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Danish literary traditions of psychological realism

- Henrik Ibsen's complex female characters

- Contemporary European melodrama

- Theatrical traditions of naturalistic acting

This Film Influenced

- Later German psychological dramas

- Early Hollywood films with complex female characters

- European war dramas of the 1920s

- Films exploring themes of female moral complexity