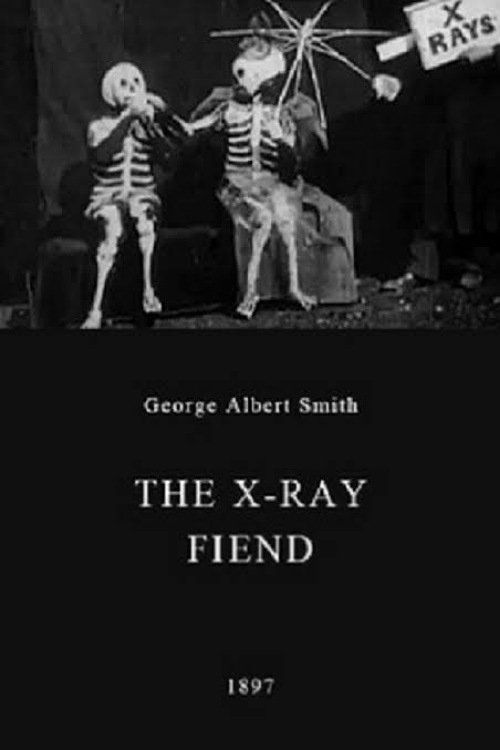

The X-Ray Fiend

Plot

In this pioneering British short film, a romantic couple (Laura Bayley and Tom Green) are enjoying an intimate moment when they are suddenly subjected to mysterious X-ray beams. The innovative special effects transform the lovers into animated skeletons who continue their romantic embrace, creating a bizarre and unsettling visual that both shocks and amuses. The film uses jump-cut techniques to create the transformation effect, showing the couple's flesh disappearing to reveal their skeletal forms beneath. The skeletal figures continue their courtship dance before eventually transforming back to their human selves, having survived this supernatural scientific experiment.

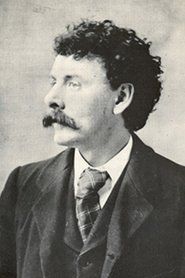

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed in George Albert Smith's Brighton studio, which was one of Britain's earliest film production facilities. The film was shot on 35mm film using a camera likely built or modified by Smith himself. The skeleton effects were achieved through careful timing and the innovative use of jump cuts, requiring precise choreography from the actors. The X-ray machine prop was constructed specifically for this production to capitalize on the public's fascination with Roentgen's recent discovery.

Historical Background

The X-Ray Fiend was produced during a period of tremendous scientific and technological advancement. The late 1890s saw the public grappling with revolutionary discoveries like X-rays, radio waves, and the cinema itself. Wilhelm Roentgen's 1895 discovery of X-rays had created worldwide sensation and fear, with newspapers filled with stories about the mysterious rays that could see through clothing and flesh. This film tapped into that mixture of wonder and anxiety about new technology. In Britain, 1897 also marked Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, a year of national celebration and technological showcase. The film industry itself was in its infancy, with the Lumière brothers having only introduced their cinématographe two years earlier. Smith's work represents the British contribution to early cinematic experimentation, running parallel to developments by Méliès in France and Edison in America.

Why This Film Matters

The X-Ray Fiend holds enormous cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of cinema engaging with contemporary scientific discoveries and public anxieties. It demonstrates how quickly filmmakers recognized cinema's potential to comment on and visualize the fears and wonders of modern life. The film represents a crucial step in the development of special effects techniques, particularly the use of jump cuts for transformation effects. It also stands as an early example of horror/science fiction genre elements that would become staples of cinema. The film's combination of romance, comedy, and horror shows the genre fluidity characteristic of early cinema. Its preservation and study today provides invaluable insight into the creative thinking of cinema's pioneers and how they responded to the technological marvels of their time.

Making Of

George Albert Smith, working from his studio in Brighton, England, created this film during the infancy of cinema. As a former magician and hypnotist, Smith was fascinated by the visual possibilities of the new medium. The production required innovative thinking - the skeleton transformation effect was achieved by filming the actors normally, then having them quickly change into skeleton costumes between takes, creating the illusion of transformation through jump cuts. Laura Bayley, Smith's wife, was not only the lead actress but also likely involved in costume design and production logistics. The film was shot on a simple hand-cranked camera, with artificial lighting needed to create the dramatic X-ray effect. The entire production would have taken only a day or two to film, typical of the rapid production schedules of early cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The X-Ray Fiend represents the state of the art in 1897. Smith used a stationary camera position, typical of early films, but demonstrated sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling through careful composition and timing. The lighting was crucial for creating the X-ray effect, likely using strong backlighting to create silhouettes and dramatic shadows. The film was shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second, the standard speed of the era. The jump-cut technique required precise camera operation and timing, as the camera had to be stopped and restarted while actors changed positions and costumes between takes.

Innovations

The X-Ray Fiend represents several important technical achievements in early cinema. Most significantly, it demonstrates one of the earliest uses of jump cuts for special effects, a technique that would become fundamental to film editing. The film also showcases early understanding of visual effects through costume and lighting manipulation. Smith's ability to create the illusion of transformation through precise timing between cuts was groundbreaking for 1897. The film also represents an early example of genre blending, combining elements of romance, comedy, and horror in a single narrative. The efficient use of the limited technology available - a single camera, basic lighting, and clever editing - shows the ingenuity of early filmmakers.

Music

Like all films of 1897, The X-Ray Fiend was originally silent. During its initial exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls, or possibly a phonograph recording in more sophisticated venues. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or chosen from existing popular pieces of the era, likely ranging from romantic melodies during the couple scenes to more dramatic or mysterious music during the transformation sequence. Modern screenings of the film are typically accompanied by period-appropriate piano music or newly composed scores.

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation sequence where the romantic couple suddenly becomes dancing skeletons through jump cuts, creating a shocking and memorable visual that exemplifies early special effects innovation

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest examples of horror/science fiction in cinema history

- The film was made just two years after Wilhelm Roentgen discovered X-rays in 1895

- Director George Albert Smith was a former stage hypnotist and magic lantern showman

- Laura Bayley was Smith's wife and frequent collaborator in his films

- The jump-cut technique used was inspired by Georges Méliès' accidental discovery in 1896

- This film is considered a precursor to both body horror and medical thriller genres

- Smith was part of the 'Brighton School' of early British filmmaking

- The skeleton effects were created by having actors wear skeleton costumes and using jump cuts

- Only one print of the film is known to survive, preserved by the BFI National Archive

- The film was originally shown as part of variety programs at music halls and fairgrounds

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception is difficult to document as film criticism was not yet established as a profession in 1897. However, the film was likely received as a novel and entertaining novelty by audiences of the time. Modern film historians and critics recognize The X-Ray Fiend as an important early work that demonstrates the rapid development of cinematic language and special effects. Scholars of early cinema particularly value it as an example of the 'Brighton School' of filmmaking and as evidence of how quickly filmmakers incorporated contemporary scientific discoveries into their work. It is frequently cited in academic studies of early horror and science fiction cinema as a foundational text.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1897 would have found The X-Ray Fiend both amusing and startling, as it played on their fascination and fear of the newly discovered X-rays. The transformation effect, achieved through jump cuts, would have seemed magical to viewers unfamiliar with film editing techniques. The film was likely shown as part of variety programs at music halls and fairgrounds, where it would have been one of many short films designed to astonish and entertain. The combination of romance, humor, and the macabre would have appealed to Victorian sensibilities while pushing the boundaries of acceptable entertainment. Modern audiences viewing the film today often express surprise at the sophistication of its effects given its 1897 production date.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Wilhelm Roentgen's 1895 discovery of X-rays

- Georges Méliès' pioneering special effects techniques

- Victorian fascination with spiritualism and the supernatural

- Magic lantern shows and theatrical special effects

This Film Influenced

- The Haunted Castle (1896) - Méliès

- The Man with the Rubber Head (1901) - Méliès

- Frankenstein (1910) - Edison Studios

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Early body horror and transformation films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in the BFI National Archive collection. While many films from this era have been lost, The X-Ray Fiend is preserved as part of the important collection of early British cinema. The surviving print shows some deterioration typical of films from this period but remains viewable. The BFI has undertaken preservation efforts to ensure this historically significant work remains accessible for future generations.