Why We Fight: The Battle of China

"The Story of the Chinese People's Heroic Struggle Against Japanese Aggression"

Plot

The sixth installment in Frank Capra's acclaimed 'Why We Fight' series, this powerful documentary chronicles Japan's brutal invasion and occupation of China that began in 1937. The film opens with historical context about China's ancient civilization before detailing Japan's aggressive expansionism, including the infamous rape of Nanking where hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians were massacred. Through compelling footage and narration, the documentary captures the Chinese people's resilience, featuring Madame Chiang Kai-shek's impassioned address to the U.S. Congress pleading for American support. The film highlights the extraordinary 2,000-mile migration of Chinese industries and universities to escape Japanese forces, and concludes with the heroic efforts of Claire Chennault's Flying Tigers, the American volunteer pilots who helped defend China before Pearl Harbor. The narrative builds a powerful case for why American intervention in the Pacific was necessary to stop Japanese aggression.

Director

About the Production

The film was created as part of the U.S. government's propaganda effort during World War II, commissioned by Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. Production faced significant challenges in obtaining authentic footage from China and Japan, relying heavily on newsreel material, smuggled footage, and Japanese propaganda films that were recontextualized. The production team worked under extreme secrecy and time pressure, completing the film in just a few months. Director Anatole Litvak, who had fled Nazi-occupied Europe, brought personal understanding of totalitarian aggression to the project. The film incorporated rare footage of the Nanking Massacre, some of which was obtained from Chinese sources and Japanese military photographers.

Historical Background

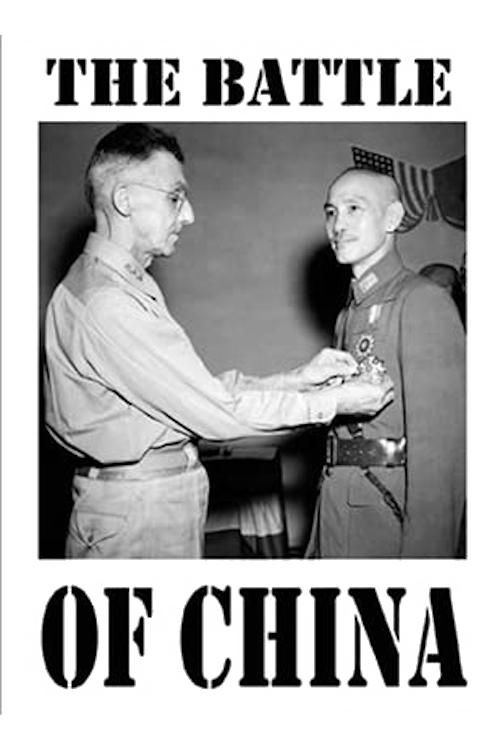

Produced in 1944, during the height of World War II, 'The Battle of China' was created at a critical juncture when the United States was fully engaged in the Pacific theater against Japan. The film was part of a comprehensive U.S. government propaganda effort to educate Americans about the global nature of the conflict and justify American involvement. At the time of its release, Allied forces were making significant progress in the Pacific, but the war against Japan was far from over. The film served to remind Americans of the long-standing Japanese aggression in Asia that had begun years before Pearl Harbor. China had been fighting Japan alone since 1937, suffering millions of casualties, and this film highlighted Chinese suffering and resistance to build American sympathy and support for the Chinese war effort. The timing was crucial as the United States was preparing for the final push against Japan, including the controversial decision to use atomic weapons. The film also reflected the wartime alliance between the U.S. and China under Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government, before the later communist revolution would change China's political landscape.

Why This Film Matters

'The Battle of China' represents a landmark in American documentary filmmaking and wartime propaganda, demonstrating how cinema could be used as a powerful tool for public education and morale building. The film was instrumental in shaping American understanding of the Sino-Japanese War and helped build support for China's struggle against Japanese aggression. It introduced many Americans to Chinese history and culture at a time when most Americans had little knowledge of Asia. The film's success in winning an Academy Award helped legitimize documentary filmmaking as a serious art form worthy of critical recognition. The 'Why We Fight' series, including this installment, established a template for future documentary war films that balanced factual reporting with emotional storytelling. The film also preserved invaluable historical footage of events like the Nanking Massacre and the Chinese migration, much of which might otherwise have been lost to history. Its influence can be seen in later documentary series that tackle complex historical subjects for mass audiences.

Making Of

The production of 'The Battle of China' was a remarkable wartime achievement, created under the auspices of the U.S. War Department's Special Service Division. Director Anatole Litvak, a European refugee who had experience with both German and American film industries, brought a unique perspective to the project. The filmmaking team faced enormous challenges obtaining authentic footage from the war zone, relying on newsreel companies, Chinese government sources, and even smuggled Japanese military footage. The editors worked tirelessly to authenticate and contextualize each piece of film, often having to translate Japanese propaganda to show the truth behind it. The narration was carefully crafted to be both informative and emotionally compelling, with Walter Huston's distinctive voice adding gravitas to the most dramatic moments. The film's score, composed by Dmitri Tiomkin, incorporated both Western and Chinese musical elements to enhance the cultural authenticity. Technical innovations included the use of animated maps to show troop movements and strategic locations, making complex military situations understandable to general audiences.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography is a masterful compilation of diverse sources, including newsreel footage, military film, and clandestinely shot material. The cinematographers faced the challenge of integrating footage from different sources, qualities, and formats into a cohesive visual narrative. The use of aerial photography to show the vastness of China and the scale of the migration was particularly effective, giving audiences a sense of the enormous distances involved. The combat footage, some of it remarkably close and dangerous, captured the intensity of the fighting between Chinese and Japanese forces. The film made effective use of contrast between beautiful shots of ancient Chinese monuments and the destruction wrought by modern warfare. The cinematography of Madame Chiang Kai-shek's speech to Congress used multiple camera angles to create a sense of importance and dignity. The Flying Tigers sequences featured some of the most exciting aerial combat footage of the era, much of it shot under actual combat conditions. The visual style combined gritty realism with carefully composed shots that enhanced the film's emotional impact.

Innovations

The film represented several technical innovations in documentary filmmaking, particularly in the realm of wartime production. The seamless integration of footage from multiple sources with different film stocks, frame rates, and conditions was a remarkable technical achievement for its time. The use of animated maps to illustrate military movements and geographical relationships was particularly sophisticated, helping audiences understand complex strategic situations. The film's editing techniques, including the use of montage to contrast Japanese propaganda with reality, were groundbreaking in their effectiveness. Sound synchronization was challenging given the varied sources of footage, but the technical team achieved remarkable clarity and consistency. The preservation and restoration of rare footage from the Nanking Massacre and other events represented an important technical achievement in historical documentation. The film's use of dual narration by different voice actors for different types of content was an innovative approach to documentary storytelling. The technical team also developed new methods for authenticating and dating historical footage, ensuring the accuracy of the historical record presented.

Music

The musical score for 'The Battle of China' was composed by the renowned Dmitri Tiomkin, who brought his distinctive dramatic sensibility to the documentary format. Tiomkin incorporated traditional Chinese musical elements into his orchestral score, creating a sound that was both authentically Asian and accessible to Western audiences. The main theme used pentatonic scales and Chinese instrumentation to evoke the ancient culture of China, while the action sequences featured Tiomkin's characteristic thunderous percussion and brass. The score for Madame Chiang Kai-shek's speech was particularly notable, using subtle underscoring that enhanced her words without overwhelming them. The Flying Tigers segments featured rousing, patriotic music that emphasized the heroism of the American volunteers. Sound design was crucial to the film's impact, with the careful use of battle sounds, aircraft engines, and crowd reactions creating an immersive experience. The musical motifs were effectively used throughout the film to create emotional continuity and highlight key moments. The soundtrack was later released as part of a compilation of Tiomkin's film music, demonstrating its artistic merit beyond the documentary context.

Famous Quotes

For centuries, China has been a great and peaceful civilization... but now, she is fighting for her very existence.

The Japanese came not as friends, but as conquerors - bringing death and destruction wherever they went.

From the ashes of their burned cities, the Chinese people rose again, determined to resist to the last man, woman, and child.

The Flying Tigers - American volunteers who flew for China before America was at war - they wrote a new chapter in the history of courage.

This is not merely a war between nations, but a struggle between civilization and barbarism, between freedom and slavery.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek told America: 'We in China want only to live in peace, but we will not live in submission.'

Memorable Scenes

- Madame Chiang Kai-shek's powerful address to the U.S. Congress, where she eloquently pleads for American support and describes China's suffering under Japanese occupation

- The harrowing footage of the Nanking Massacre, showing the brutal reality of Japanese war crimes against Chinese civilians

- The extraordinary sequence depicting the 2,000-mile migration, where entire universities and factories are dismantled and moved inland to escape Japanese forces

- The thrilling aerial combat footage of the Flying Tigers in action, showing their daring attacks against superior Japanese forces

- The opening sequence contrasting China's ancient civilization with the modern destruction brought by Japanese invasion

- The animated map sequences that clearly illustrate Japanese expansion and Chinese resistance strategies

- The closing scenes showing Chinese determination to continue fighting despite overwhelming odds, set to rousing patriotic music

Did You Know?

- This was the sixth of seven films in the 'Why We Fight' series directed by Frank Capra, though this particular installment was directed by Anatole Litvak

- The film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1945, sharing the honor with 'The Fighting Lady'

- Madame Chiang Kai-shek's speech to Congress was actually delivered in 1943, a year before the film's release

- The Flying Tigers footage was particularly valuable as it showed American involvement in China before Pearl Harbor

- The film's narration was handled by both Anthony Veiller and Walter Huston, with Huston providing the more dramatic segments

- Some footage used in the film was captured from Japanese sources and repurposed to show the reality of their invasion

- The 2,000-mile migration depicted in the film involved moving entire universities and factories inland to escape Japanese forces

- The film was shown not only to American troops but also to civilian audiences in theaters as part of the war effort

- Claire Chennault, leader of the Flying Tigers, served as a technical consultant for the film

- The series was originally intended only for military personnel but was so effective that President Roosevelt ordered it released to the public

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Battle of China' for its powerful storytelling and effective use of documentary footage. The New York Times called it 'a stirring and informative document that makes the case for China's resistance with compelling clarity.' Variety noted that 'the film's emotional impact is matched by its historical accuracy, making it both propaganda and valuable history.' Modern critics have reassessed the film as both an effective wartime propaganda piece and a historically significant documentary. Film historian Thomas Schatz has written that the film 'represents the pinnacle of government-sponsored documentary filmmaking, achieving its propagandistic aims without sacrificing artistic merit.' The British Film Institute has included it in their list of important wartime documentaries, noting its 'sophisticated narrative structure and powerful visual storytelling.' Some contemporary critics have pointed out the film's limitations as a product of its time, particularly its uncritical portrayal of Chiang Kai-shek's regime and its failure to address the complex political situation within China. However, most agree that it remains an important historical document and an example of documentary filmmaking at its most purposeful.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enthusiastically received by both military and civilian audiences during its original release. Soldiers reported that the film helped them understand the broader context of their fight in the Pacific and gave them a greater appreciation for their Chinese allies. Civilian audiences, who were seeing much of this footage for the first time, were reportedly shocked by the brutality of the Japanese invasion and moved by Chinese resilience. The film's theatrical release was well-attended, with many theaters reporting sell-out crowds. Audience letters to newspapers and the War Department expressed gratitude for the film's educational value and emotional impact. In China, where the film was shown to boost morale, it was received with particular enthusiasm, with Chinese audiences reportedly cheering during the Flying Tigers sequences. The film's effectiveness in building pro-Chinese sentiment among Americans was noted in government surveys conducted after the war. Modern audiences viewing the film through historical lenses often express admiration for its craftsmanship while noting its propagandistic elements, but many find its documentation of Japanese war crimes particularly powerful and historically important.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature (1945)

- New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Documentary (1944)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Leni Riefenstahl's 'Triumph of the Will' (as a counter-example to be deconstructed)

- British documentary movement of the 1930s

- Frank Capra's narrative film techniques

- John Ford's documentary 'The Battle of Midway'

- Newsreel journalism traditions

- Wartime propaganda films from Britain

This Film Influenced

- The 'Why We Fight' series sequels

- Post-war documentary series on WWII

- Ken Burns' documentary series

- Modern historical documentaries on the Pacific War

- Government-sponsored documentary films

- Educational war documentaries

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the National Archives and Records Administration as part of the official record of World War II. The Library of Congress maintains a copy in its motion picture collection, and the film has been digitized as part of various WWII preservation projects. The original 35mm nitrate elements have been transferred to safety stock, and multiple restoration efforts have been undertaken to improve image and sound quality. The Academy Film Archive also maintains a preserved copy as part of its Oscar-winning films collection. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition, though some of the compiled footage shows the wear and deterioration common to wartime documentary material. Several versions exist, including the original theatrical release and slightly different versions shown to military audiences. The film entered the public domain years ago, which has contributed to its widespread availability but also to the circulation of lower-quality copies.