Leonid Lukov

Director

About Leonid Lukov

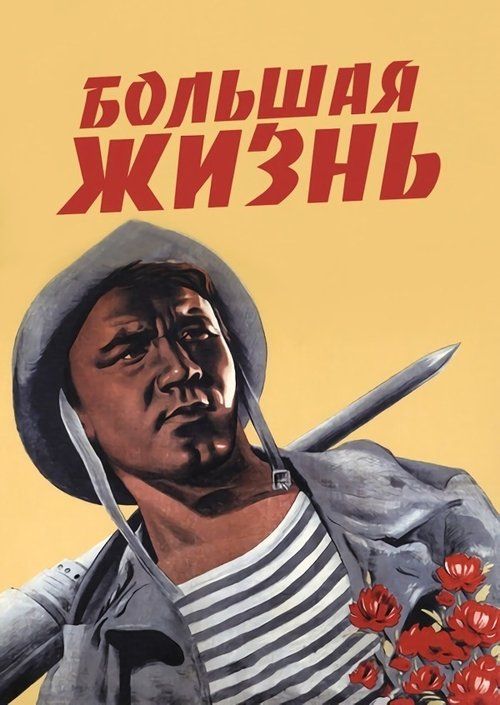

Leonid Lukov was a prominent Soviet film director who rose to prominence during the Stalinist era, specializing in socialist realist cinema that celebrated industrial labor and Soviet achievements. He began his career in the late 1930s, establishing himself with his debut feature 'A Great Life' (1939), which garnered critical acclaim and set the tone for his future work. During World War II, Lukov contributed to the war effort by creating propaganda films, including 'Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #8' (1942), which showcased Soviet military strength and resilience. His post-war period saw him continue his focus on industrial themes with films like 'It Happened in the Donbass' (1945) and 'The Miners of Donetsk' (1951), which depicted the heroic struggles and triumphs of Soviet workers. Lukov's directing style was characterized by its straightforward narrative approach, emphasis on collective heroism, and adherence to the principles of socialist realism mandated by the Soviet state. Despite the ideological constraints of his time, he managed to create technically proficient films that resonated with Soviet audiences and received official recognition from the state. His career, while primarily confined to the Soviet system, represents an important chapter in the history of Russian cinema during the mid-20th century.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Lukov's directing style was firmly rooted in socialist realism, characterized by straightforward narratives, heroic portrayals of workers, and optimistic depictions of Soviet progress. His films emphasized collective achievement over individual glory, featuring strong visual compositions that highlighted industrial landscapes and the dignity of labor. Lukov employed conventional cinematic techniques with clear storytelling, avoiding experimental approaches in favor of accessible, ideologically sound entertainment that aligned with Soviet cultural policies.

Milestones

- Directed 'A Great Life' (1939) which received Stalin Prize

- Created wartime propaganda films during WWII

- Established himself as a leading director of industrial-themed films

- Received multiple state awards for contributions to Soviet cinema

- Mentored younger directors in the Soviet film industry

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Stalin Prize (Second Class) for 'A Great Life' (1941)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1950)

- Honored Artist of the RSFSR (1950)

Special Recognition

- People's Artist of the RSFSR (1957)

- Order of the Badge of Honour

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Leonid Lukov's films played a significant role in shaping Soviet cultural identity during the mid-20th century, particularly in promoting the values of socialist realism and the glorification of industrial labor. His work contributed to the Soviet state's efforts to create a cinematic language that celebrated collective achievement and the dignity of the working class. While his films were ideologically driven, they also provided Soviet audiences with entertainment that reflected their own experiences and aspirations, helping to reinforce national unity during and after World War II. Lukov's focus on industrial themes helped establish a subgenre of Soviet cinema that explored the relationship between technology, labor, and human progress.

Lasting Legacy

Leonid Lukov's legacy lies in his contribution to Soviet cinema's golden age of socialist realism, where he helped define the visual and narrative conventions of industrial-themed filmmaking. His films remain important historical documents that reflect the cultural and political values of their time, offering insight into how cinema was used as a tool for social education and ideological reinforcement. While his work may be less known internationally, Lukov is remembered in Russian film history as a skilled craftsman who successfully navigated the complex demands of the Soviet film industry while creating technically proficient and emotionally resonant films that spoke to Soviet audiences.

Who They Inspired

Lukov influenced several generations of Soviet directors who followed in his footsteps, particularly those working within the socialist realist tradition. His approach to depicting industrial subjects and working-class heroes provided a template for subsequent filmmakers tackling similar themes. While his influence was primarily confined to the Soviet sphere, his work represents an important example of how cinema can be used to promote social and political values, a lesson that has relevance for understanding the relationship between art and ideology in any cultural context.

Off Screen

Leonid Lukov was married and had children, though detailed information about his family life remains limited in publicly available sources. He lived and worked primarily in Moscow during his active years as a director. His personal life was largely overshadowed by his professional commitments and the demands of working within the Soviet film system, where political conformity was essential for career advancement.

Education

Graduated from the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow, where he studied film directing during the early 1930s

Family

- Information not publicly available

Did You Know?

- His film 'A Great Life' was so well-received that it earned him the prestigious Stalin Prize in 1941

- Lukov often filmed on location in actual industrial settings to achieve greater authenticity

- During WWII, he was part of a special group of directors assigned to create morale-boosting films for Soviet troops

- His films were frequently shown in workers' clubs and factories as part of Soviet cultural education programs

- Lukov was known for his meticulous attention to detail in depicting industrial processes on screen

- He survived the Stalinist purges that affected many of his contemporaries in the film industry

- Several of his films were exported to other Eastern Bloc countries as examples of exemplary Soviet cinema

- Lukov was particularly respected for his ability to make industrial subjects cinematically engaging

- His later career was hampered by health problems that limited his output in the 1950s and early 1960s

- Despite ideological constraints, Lukov managed to infuse his films with genuine human drama and emotion

In Their Own Words

The cinema must serve the people and illuminate their path toward a better future

In depicting the worker, we depict the hero of our time

Every film should be both a mirror and a window - reflecting our reality and showing us what we can become

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Leonid Lukov?

Leonid Lukov was a Soviet film director active from the late 1930s to early 1960s, known for his socialist realist films that celebrated industrial workers and Soviet achievements. He was particularly recognized for films like 'A Great Life' and 'The Miners of Donetsk,' which exemplified the state-approved cinematic style of his era.

What films is Leonid Lukov best known for?

Lukov is best known for 'A Great Life' (1939), which won the Stalin Prize, 'It Happened in the Donbass' (1945), 'The Miners of Donetsk' (1951), and his wartime propaganda film 'Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #8' (1942). These films established his reputation as a leading director of industrial-themed cinema.

When was Leonid Lukov born and when did he die?

Leonid Lukov was born on May 2, 1909, in Mariupol, Russian Empire (now Ukraine), and died on April 15, 1963, in Moscow, Soviet Union. His career spanned from 1939 until his death, covering some of the most significant years in Soviet cinema history.

What awards did Leonid Lukov win?

Lukov received the Stalin Prize (Second Class) for 'A Great Life' in 1941, was named Honored Artist of the RSFSR in 1950, and later became People's Artist of the RSFSR in 1957. He also received state honors including the Order of the Red Banner of Labour and the Order of the Badge of Honour.

What was Leonid Lukov's directing style?

Lukov's directing style was characterized by socialist realism, featuring straightforward narratives, heroic portrayals of workers, and optimistic depictions of Soviet progress. He emphasized collective achievement over individual glory and used clear, accessible storytelling techniques that aligned with Soviet cultural policies while maintaining technical proficiency.

Learn More

Films

4 films