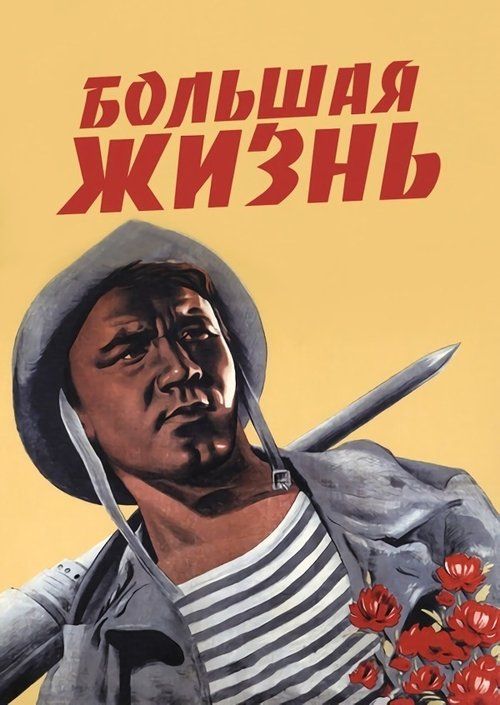

A Great Life

"The story of Soviet miners building socialism"

Plot

The film follows the story of Khariton Balun, a young and enthusiastic miner who arrives in the Donbas coal mining region of the Ukrainian SSR to help with industrialization efforts. He quickly discovers that the mine is suffering from systematic sabotage orchestrated by counter-revolutionary elements who are deliberately causing accidents and lowering production quotas. Along with experienced miner Kuzma Izotov and other dedicated workers, Khariton must identify the saboteurs while battling both the dangerous working conditions and the human elements trying to undermine Soviet industrial progress. The film portrays the miners' struggle to modernize their operations and increase coal production to meet the demands of the Five-Year Plan, all while maintaining their revolutionary spirit and commitment to the socialist cause. Through their efforts, they ultimately expose and defeat the saboteurs, proving the superiority of collective socialist labor over individual sabotage and capitalist subversion.

About the Production

Filmed on location in actual coal mines to ensure authenticity, with many real miners appearing as extras. The production faced significant challenges due to the dangerous filming conditions in active mines. Director Leonid Lukov insisted on using natural lighting and real mining equipment to enhance realism.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the height of Stalin's Great Purge (1936-1938) and just before the outbreak of World War II. This was a period of intense industrialization in the Soviet Union under the Five-Year Plans, with the Donbas region being crucial for coal production. The film's emphasis on saboteurs and enemies of the people reflected the paranoid atmosphere of the era, where genuine industrial accidents were often attributed to deliberate sabotage. The timing of its release in September 1939 coincided with the Soviet invasion of Poland, making the film's themes of vigilance against enemies particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. The film served as both entertainment and propaganda, reinforcing the importance of industrial production for Soviet military preparedness.

Why This Film Matters

A Great Life became one of the canonical examples of Socialist Realism in Soviet cinema, establishing many tropes that would be repeated in subsequent industrial films. It helped create the archetype of the enthusiastic young worker coming to help with industrialization, a character type that appeared in numerous Soviet films and literature. The film's success demonstrated the Soviet audience's appetite for stories about ordinary workers achieving extraordinary results through collective effort. It influenced how Soviet industry was portrayed in cinema for decades, emphasizing the heroic nature of manual labor and the constant threat of sabotage. The film's visual language and narrative structure became templates for other industrial dramas produced during the Stalin era.

Making Of

Director Leonid Lukov spent several months living in mining communities before filming to understand the miners' lives and working conditions. The cast underwent training in actual mining techniques to perform their roles authentically. Many scenes were shot in working mines during production breaks, requiring careful coordination with mine management. The film's script went through multiple revisions to satisfy Soviet cultural authorities, who wanted to emphasize the heroism of Soviet workers while maintaining the dramatic tension of the saboteur subplot. The production team worked closely with local party officials to ensure the film aligned with current Soviet ideological goals regarding industrialization and class struggle.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Boris Monastyrev emphasized the stark contrast between the darkness of the mines and the bright hope of socialist progress. Low-angle shots were used to make the miners appear heroic and larger than life. The film employed innovative lighting techniques for the mining scenes, using actual mining lamps to create authentic shadows and highlights. Long tracking shots through the mine tunnels gave audiences a sense of the dangerous working conditions. The visual style combined documentary realism with the heightened drama typical of Socialist Realism, creating a distinctive aesthetic that influenced subsequent Soviet industrial films.

Innovations

The film pioneered new techniques for filming in confined underground spaces, using custom-built camera rigs that could navigate narrow mine tunnels. The production team developed special lighting equipment that could operate safely in the explosive environment of coal mines. Sound recording in the noisy mining environment required innovative microphone placement and post-production techniques. The film's realistic depiction of mining accidents and rescue operations set new standards for action sequences in Soviet cinema. The seamless integration of documentary footage of actual mines with studio-shot scenes was technically advanced for its time.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, one of the Soviet Union's most prominent composers. The soundtrack featured stirring orchestral themes that emphasized the heroic nature of the miners' work, with martial motifs during the struggle against saboteurs and triumphant music during successful production efforts. Traditional Ukrainian folk melodies were incorporated into the score to emphasize the regional setting. The film included several workers' songs that became popular in their own right and were sung in factories and mines across the USSR. The sound design paid careful attention to the authentic sounds of mining machinery, recorded on location in actual Donbas mines.

Famous Quotes

Every ton of coal is a blow against the enemies of socialism!

We don't just mine coal, we build the future!

A miner's lamp is brighter than any star when it lights the path to socialism!

The earth gives us its treasures, but we must earn them with our sweat and our vigilance!

In the darkness of the mine, we see the light of tomorrow most clearly!

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic mine collapse sequence where workers risk their lives to save trapped comrades, showcasing their bravery and solidarity

- The confrontation scene where Khariton exposes the saboteurs during a workers' meeting, leading to their arrest

- The final montage of increased coal production with triumphant music playing as the miners celebrate exceeding their quotas

- The opening sequence showing the vast Donbas mining landscape with smokestacks against the sky, establishing the industrial setting

Did You Know?

- The film was so popular that a sequel, 'A Great Life, Part 2' was released in 1946, though it was heavily criticized and withdrawn from circulation

- Stalin personally praised the film for its positive portrayal of Soviet workers

- Many of the mining scenes were filmed in dangerous conditions with the actors working alongside real miners

- The film was one of the most popular Soviet releases of 1939, seen by millions across the USSR

- Pyotr Aleynikov, who played Khariton Balun, became one of the most popular Soviet actors of the 1940s after this role

- The film was temporarily banned during the Khrushchev thaw for being too Stalinist in its ideology

- Real Donbas miners served as technical consultants during filming

- The saboteur plot elements reflected genuine concerns about industrial sabotage during the pre-war period

- The film's success led to Lukov being awarded the title 'Honored Artist of the RSFSR'

- Coal mining equipment shown in the film was actual working machinery from the 1930s Donbas mines

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterpiece of Socialist Realism, with Pravda calling it 'a true monument to the Soviet working class.' Western critics had limited access to the film initially, but those who saw it noted its technical competence while criticizing its heavy-handed propaganda elements. During the Khrushchev era, the film was re-evaluated as an example of Stalinist excess in cinema. Modern film historians recognize it as an important artifact of its time, noting both its artistic merits within the constraints of Socialist Realism and its value as a historical document of Soviet industrial propaganda.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences, with millions viewing it across the USSR. Many miners in the Donbas region reported feeling proud to see their work portrayed on screen. The character of Khariton Balun became particularly beloved, with young workers emulating his enthusiasm and dedication. Audience letters to newspapers praised the film's realism and emotional impact. The film's popularity led to it being shown repeatedly in workers' clubs and factories throughout the 1940s. Despite its ideological content, audiences responded to the human drama and working-class solidarity depicted in the film.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, First Class (1941) - awarded to director Leonid Lukov and lead actors

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor (1939) - awarded to the production team

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Chapaev (1934) - for its portrayal of revolutionary heroism

- The Great Citizen (1938) - for its themes of vigilance against enemies

- Maxim's Trilogy (1935-1938) - for its coming-of-age narrative structure

- Soviet industrial literature of the 1930s

This Film Influenced

- A Great Life, Part 2 (1946)

- The Kuban Cossacks (1949)

- The Vow (1946)

- The Fall of Berlin (1949)

- Numerous Soviet industrial dramas of the 1940s and 1950s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia and the Ukrainian National Film Archive. A restored version was released in 2005 as part of a collection of classic Soviet films. The original negative is stored in climate-controlled facilities, though some minor deterioration is evident. The film has been digitized and is available in both Russian and Ukrainian language versions. Several prints survive in international archives, including the British Film Institute and the Library of Congress.