Władysław Starewicz

Director

About Władysław Starewicz

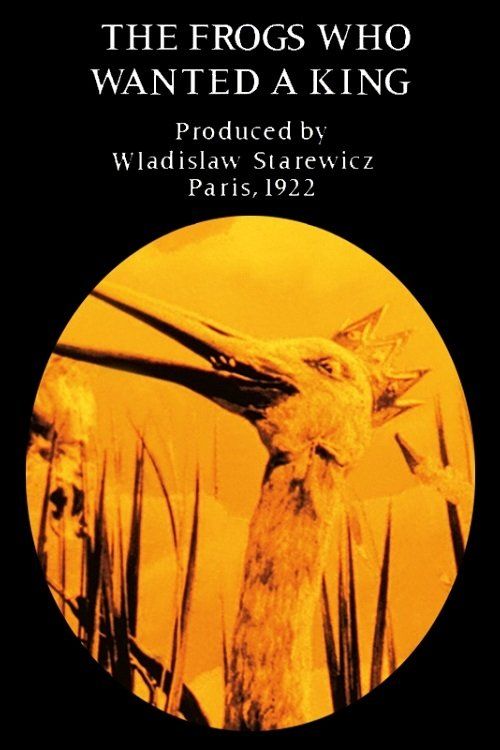

Władysław Starewicz (also spelled Ladislas Starevich) was a pioneering Russian and Polish stop-motion animator and director who revolutionized early cinema through his innovative use of puppet animation. Born in Moscow to Polish parents, he initially worked as a naturalist and entomologist before discovering his passion for filmmaking. His breakthrough came in 1910 when he created 'The Battle of the Stag Beetles,' considered the first puppet-animated film, after discovering that dead beetles could be animated by repositioning their limbs. After the Russian Revolution, Starewicz moved to France where he established his own studio and continued creating elaborate stop-motion masterpieces throughout the 1920s and 1930s. His most famous works include 'The Cameraman's Revenge' (1912), 'The Tale of the Fox' (1930), and 'Fétiche Mascotte' (1934), which showcased his technical mastery and artistic vision. Starewicz's films were renowned for their intricate detail, dark humor, and sophisticated storytelling that appealed to both children and adults. He continued working until his death in 1965, leaving behind a legacy that influenced generations of animators from Ray Harryhausen to the creators of Aardman Animations.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Starewicz's directing style was characterized by meticulous attention to detail, dark humor, and sophisticated narrative techniques. He pioneered the use of dead insects and articulated puppets to create lifelike movements, often infusing his characters with human emotions and social commentary. His films blended fantasy with reality, using miniature sets and elaborate lighting to create immersive worlds that were both whimsical and psychologically complex.

Milestones

- Created the first puppet-animated film 'The Battle of the Stag Beetles' (1910)

- Directed the groundbreaking 'The Cameraman's Revenge' (1912)

- Produced France's first feature-length animated film 'The Tale of the Fox' (1930)

- Won numerous international awards for his innovative animation techniques

- Established his own animation studio in Paris after emigrating from Russia

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Honorary Mention at Venice Film Festival for 'The Tale of the Fox' (1937)

- Best Animation Award at Venice Film Festival for 'Fétiche Mascotte' (1934)

- Special Jury Prize at Cannes Film Festival (1946)

- Order of Polonia Restituta (Polish state decoration)

Nominated

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion nomination for 'The Tale of the Fox' (1937)

Special Recognition

- Recognized as one of animation's founding fathers by ASIFA-Hollywood

- Inducted into the Animation Hall of Fame

- Retrospective exhibitions at major film museums worldwide

- Subject of documentary 'The Bug Trainer' (2008)

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Władysław Starewicz fundamentally changed the course of animation history by inventing and perfecting stop-motion puppet animation techniques that would become industry standards. His work demonstrated that animation could be a sophisticated art form capable of complex storytelling and emotional depth, challenging the perception that animation was merely children's entertainment. Starewicz's films introduced technical innovations like replacement animation, articulated metal armatures, and sophisticated miniature set design that are still used in modern stop-motion production. His unique blend of dark humor, social commentary, and technical mastery influenced countless animators and helped establish stop-motion as a legitimate cinematic art form.

Lasting Legacy

Starewicz's legacy endures through his preserved films, which continue to be screened at film festivals and studied in animation schools worldwide. His techniques and artistic vision laid the groundwork for modern stop-motion animation, from Ray Harryhausen's creature effects to contemporary studios like Aardman Animations and Laika. The annual ASIFA-Hollywood Annie Awards include a category named in his honor, recognizing excellence in stop-motion animation. His films are preserved in major film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art, ensuring that future generations can study and appreciate his pioneering work. Many of his techniques, such as the use of ball-and-socket armatures, remain fundamental to stop-motion animation today.

Who They Inspired

Starewicz directly influenced pioneering animators including Lotte Reiniger, who adapted his silhouette techniques, and Jiří Trnka, who credited Starewicz as a major inspiration for his puppet films. Ray Harryhausen cited Starewicz's work as an early influence on his monster effects, while modern directors like Tim Burton and Henry Selick have acknowledged his impact on their stop-motion aesthetic. Contemporary animators at studios like Laika and Aardman continue to use techniques pioneered by Starewicz, particularly in the areas of puppet articulation and miniature set construction. His approach to infusing inanimate objects with personality and emotion can be seen in everything from Pixar's early films to modern stop-motion features like 'Coraline' and 'Kubo and the Two Strings'.

Off Screen

Starewicz married Anna Zimmermann, a French woman of German descent, who became his frequent collaborator and assistant. The couple had two daughters, Irène and Nina, both of whom worked in their father's studio as animators and voice actors. The family lived in Fontenay-aux-Roses, a suburb of Paris, where Starewicz built his animation studio. Despite his artistic success, Starewicz remained a private person who rarely gave interviews, preferring to let his work speak for itself. His daughter Irène continued the family tradition, working as an animator and preserving her father's legacy after his death.

Education

Studied natural sciences and entomology at the University of Moscow; self-taught in animation and filmmaking techniques

Family

- Anna Zimmermann (1911-1965, his death)

Did You Know?

- He originally used dead insects in his early animations because live ones wouldn't cooperate

- His film 'The Tale of the Fox' took 18 months to animate and was the first feature-length puppet animation film

- Starewicz was a trained entomologist and his scientific background influenced his anatomically accurate insect animations

- His daughter Irène provided the voice for the main character in 'Fétiche Mascotte'

- Many of his original puppets and sets were destroyed during World War II

- He created over 100 films during his career, though many have been lost

- Starewicz was fluent in Russian, Polish, French, and German

- His films were among the first to use sound in puppet animation

- He built his own cameras and animation equipment to achieve specific effects

- His work was so technically advanced that modern animators still study his techniques

- He was one of the first animators to use replacement animation for facial expressions

- His films were banned in some countries for their dark themes and social commentary

In Their Own Words

I discovered that I could animate dead insects by moving their legs one frame at a time

Animation is not about making things move, but about making them live

Every puppet has a soul, you just have to discover it

The camera is my pencil, the puppets are my actors

I don't make films for children, I make films that children can understand

Stop-motion is the most honest form of animation - what you see is what was really there

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Władysław Starewicz?

Władysław Starewicz was a pioneering Russian-Polish animator and director who invented stop-motion puppet animation in the early 1910s. He is considered one of the founding fathers of animation, known for his innovative techniques using articulated puppets and dead insects to create lifelike animated films.

What films is Władysław Starewicz best known for?

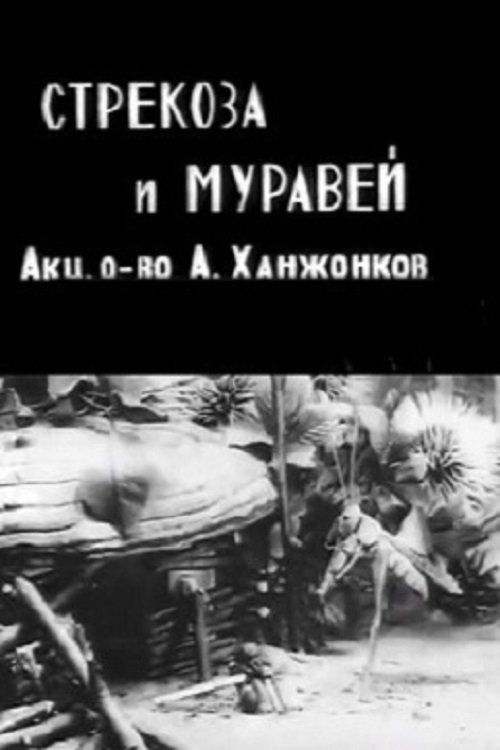

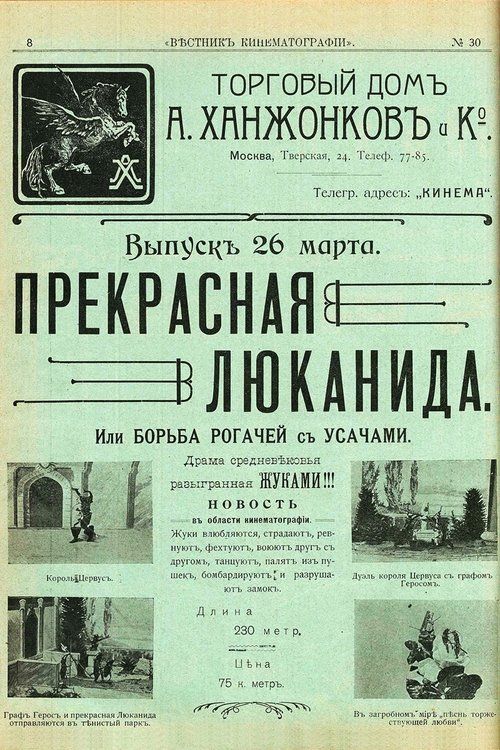

Starewicz is most famous for 'The Cameraman's Revenge' (1912), a dark comedy about infidelity among insects, 'The Tale of the Fox' (1930), the first feature-length puppet animation film, and 'Fétiche Mascotte' (1934), which won the Best Animation Award at Venice. His other notable works include 'The Insects' Christmas' (1911) and 'The Beautiful Leukanida' (1912).

When was Władysław Starewicz born and when did he die?

Władysław Starewicz was born on August 8, 1882, in Moscow, Russian Empire, to Polish parents. He died on February 26, 1965, in Fontenay-aux-Roses, France, at the age of 82, leaving behind a legacy that spanned over five decades of animation innovation.

What awards did Władysław Starewicz win?

Starewicz received numerous international accolades including the Best Animation Award at the Venice Film Festival for 'Fétiche Mascotte' (1934), an Honorary Mention for 'The Tale of the Fox' (1937), and a Special Jury Prize at Cannes (1946). He was also awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta, one of Poland's highest civilian honors, for his contributions to art and culture.

What was Władysław Starewicz's directing style?

Starewicz's directing style combined meticulous technical precision with dark humor and sophisticated storytelling. He pioneered techniques like replacement animation and articulated metal armatures, creating films that blended fantasy with reality. His work often featured social commentary and psychological depth, using puppets and insects to explore complex human emotions and relationships.

How did Władysław Starewicz influence modern animation?

Starewicz's innovations directly influenced generations of animators from Ray Harryhausen to modern studios like Laika and Aardman Animations. His techniques for puppet articulation, miniature set design, and replacement animation remain fundamental to stop-motion production today. His artistic approach demonstrated that animation could address sophisticated themes and appeal to adult audiences.

Why did Władysław Starewicz use insects in his animations?

As a trained entomologist, Starewicz had a scientific understanding of insect anatomy and movement. He discovered that dead insects could be animated frame by frame after live specimens refused to cooperate for filming. This led to his breakthrough technique of using articulated insects and puppets, which became his signature style and revolutionized early animation.

Learn More

Films

7 films