The Night Before Christmas

Plot

On Christmas Eve in a Ukrainian village, the blacksmith Vakula, who is the son of a witch, desperately wants to marry the beautiful Oksana. Oksana, however, sets an impossible condition: she will only marry him if he brings her the slippers worn by the Tsarina herself. Desperate to prove his love, Vakula encounters a mischievous devil who has been tormenting the village. Using his wit and his mother's magical knowledge, Vakula manages to trap the devil and forces him to fly him to St. Petersburg to obtain the coveted slippers. After successfully retrieving the shoes and returning to the village, Vakula wins Oksana's hand in marriage, while the humbled devil learns a lesson about interfering with human affairs.

About the Production

This film was groundbreaking for its time, combining live-action sequences with innovative stop-motion animation techniques. Starewicz used actual taxidermied insects and articulated puppets for the animated sequences, a technique he had pioneered. The production faced significant technical challenges due to the primitive equipment available in 1913, requiring multiple exposures and careful frame-by-frame manipulation. The devil character was particularly complex to animate, requiring dozens of articulated joints to achieve the desired expressive movements.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema, a period from roughly 1908 to 1917 when Russian filmmakers were developing their own cinematic language distinct from Western influences. This era saw the emergence of sophisticated literary adaptations, as Russian filmmakers sought to elevate cinema from mere entertainment to art. The Khanzhonkov Company, which produced this film, was one of Russia's most important early studios, competing with foreign imports by creating high-quality domestic productions. 1913 was also the year of the Romanov dynasty's tercentenary, creating a cultural atmosphere that celebrated Russian folklore and literature. The film's release coincided with growing technical sophistication in Russian cinema, as filmmakers moved away from simple theatrical recordings toward more complex cinematic techniques including location shooting, special effects, and sophisticated editing.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest successful adaptations of Russian literature to the screen, helping establish a tradition of literary cinema in Russia. It represents a crucial moment in the development of special effects and animation techniques that would influence filmmakers worldwide. Starewicz's innovative use of stop-motion animation predates many Western pioneers and demonstrates how Russian cinema was contributing to global film language development. The film also preserves a visual interpretation of Ukrainian folklore and Gogol's literary vision from the early 20th century, serving as a cultural artifact of how Russians viewed their multicultural empire. Its success helped prove that Russian cinema could compete with foreign imports on artistic merit rather than just price, encouraging further investment in domestic film production. The film's blend of comedy, fantasy, and horror elements also established genre conventions that would influence Russian cinema for decades.

Making Of

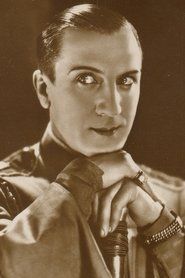

The production of 'The Night Before Christmas' was a remarkable achievement in early cinema, representing Władysław Starewicz's mastery of combining live-action with stop-motion animation. Starewicz, working with the Khanzhonkov Company, employed his signature technique of using dead insects and articulated puppets for the supernatural elements. The devil character was particularly challenging to create, requiring months of meticulous work to design and build a puppet that could express emotion and movement. The live-action sequences, featuring the rising star Ivan Mosjoukine, were filmed on constructed sets that replicated Ukrainian village architecture. The integration between live-action and animated elements was accomplished through careful matte work and multiple exposures, techniques that were cutting-edge for 1913. The production team reportedly worked through harsh winter conditions to capture authentic snow scenes, with the cast having to perform in freezing temperatures while wearing period costumes that offered little protection from the cold.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Siversen was highly advanced for its time, featuring sophisticated use of lighting to create atmospheric effects for the supernatural sequences. The film employed innovative techniques such as multiple exposure for the flying scenes and careful manipulation of focus to blend live-action with animated elements. The winter scenes benefited from natural snow, creating authentic visual textures that studio lighting of the period could not replicate. The cinematographer used pioneering close-up techniques for emotional moments, particularly in scenes between Vakula and Oksana, helping establish the psychological depth of the characters. The camera work during the animated sequences required precise frame-by-frame coordination, with the cinematographer needing to maintain consistent lighting and focus over extended periods of stop-motion work. The visual style successfully blended the romantic realism of the live-action sequences with the fantastical elements of the animation, creating a cohesive visual world that supported the story's magical elements.

Innovations

This film represents several major technical breakthroughs in early cinema. Starewicz's stop-motion animation techniques were years ahead of similar developments in Western cinema, with his method of using articulated puppets and taxidermied animals creating unprecedented realism in animated movement. The integration of live-action and animation through multiple exposure techniques was groundbreaking, requiring precise planning and execution. The flying effects for the devil character were achieved through a combination of stop-motion and careful matte work, creating illusions that would not become common in cinema for another decade. The film's special effects also included early examples of forced perspective and scale manipulation to make the animated characters appear to interact naturally with live actors. The production also pioneered techniques for creating convincing snow and winter effects on camera, using real snow and careful lighting to avoid the flat appearance common in early winter scenes. These technical innovations influenced both Russian and international filmmakers, with Starewicz's methods being studied and adapted by animators worldwide.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Night Before Christmas' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical Russian cinema of 1913 would have featured a pianist or small orchestra playing selections from classical Russian composers like Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, or Mussorgsky. The musical accompaniment would have been carefully chosen to match the film's changing moods - romantic themes for the love scenes, dramatic music for the supernatural encounters, and folk melodies for the village scenes. Some theaters may have used popular Russian folk songs or Christmas carols during the Christmas Eve sequences. Modern restorations of the film have been scored by contemporary composers who attempt to recreate the musical atmosphere of early 20th-century Russian cinema. The lack of an original recorded soundtrack means that each viewing experience can be unique depending on the musical interpretation chosen for accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'I will marry none but Vakula, if he brings me the Tsarina's shoes!' - Oksana's impossible condition

'Even the devil cannot resist a determined blacksmith!' - Narrator's observation

'Christmas Eve is when miracles happen for those who believe' - Opening intertitle establishing the magical atmosphere

'Love can make a man fly, even without wings' - Romantic intertitle during the flying sequence

Memorable Scenes

- The devil's first appearance, where Starewicz's stop-motion animation brings the supernatural character to life with unprecedented realism for 1913

- Vakula trapping the devil through clever use of religious symbols, showcasing the film's blend of folklore and Christian themes

- The flying sequence over the Russian landscape, combining innovative special effects with beautiful winter cinematography

- The climactic scene in St. Petersburg where Vakula obtains the Tsarina's slippers, demonstrating the film's elaborate production design

- The final Christmas celebration where Vakula returns with the shoes and wins Oksana's hand, bringing together all the film's thematic elements

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films to adapt Nikolai Gogol's supernatural tales to the screen, helping establish a tradition of Russian fantasy cinema

- Władysław Starewicz was originally trained as an entomologist, which influenced his revolutionary use of insects in animation

- The film's devil character required over 30 separate joints for articulation, making it one of the most complex animated puppets of its time

- Ivan Mosjoukine, who played the blacksmith Vakula, would later become one of the most celebrated Russian film actors and emigrated to France after the revolution

- The special effects showing the devil flying were achieved through a combination of stop-motion animation and multiple exposure techniques that were revolutionary for 1913

- The film was nearly lost during the Russian Revolution but survived through copies that had been exported to other countries

- Starewicz reportedly used real beetle wings for the devil's animated movements, leveraging his knowledge of insect anatomy

- The Tsarina's slippers shown in the film were actual antique footwear borrowed from a Moscow museum collection

- This film was part of a series of literary adaptations produced by the Khanzhonkov Company to elevate Russian cinema's cultural status

- The winter scenes were shot during an actual Russian winter, with the cast and crew enduring temperatures well below freezing

What Critics Said

Contemporary Russian critics praised the film for its technical innovation and successful adaptation of Gogol's beloved story. The magazine 'Kine-Zhurnal' specifically highlighted Starewicz's revolutionary animation techniques as a breakthrough for Russian cinema. Critics noted how the film managed to capture the supernatural elements of Gogol's tale in a way that stage adaptations could not achieve. The performances, particularly Ivan Mosjoukine's portrayal of Vakula, were praised for their naturalism compared to the exaggerated acting common in films of the period. Modern film historians consider this work a landmark in early cinema, with scholars like Jay Leyda and Yuri Tsivian citing it as evidence of Russian cinema's early sophistication. The film is now recognized as a crucial stepping stone in the development of both animation and special effects cinema, with Starewicz's techniques studied by animation historians worldwide.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly popular with Russian audiences upon its release in December 1913, particularly appealing to educated viewers who were familiar with Gogol's literary work. Audiences were reportedly amazed by the special effects, especially the flying sequences and the animated devil, which were unlike anything they had seen before. The combination of familiar Russian literature with cutting-edge visual effects made the film a talking point in Moscow cultural circles. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film ran for several weeks in Moscow cinemas, which was considered a successful run for the period. The film's popularity helped establish both Ivan Mosjoukine as a major star and Władysław Starewicz as a pioneering director. Modern audiences who have seen restored versions of the film continue to be impressed by its technical achievements, with many noting how the stop-motion animation remains remarkably effective more than a century later.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nikolai Gogol's 'The Night Before Christmas' from 'Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka'

- Ukrainian folk tales and Christmas traditions

- Russian Orthodox Christmas customs

- Earlier Russian literary adaptations by Khanzhonkov Company

- Georges Méliès's trick films and special effects techniques

This Film Influenced

- Starewicz's later animated works including 'The Cameraman's Revenge' (1912) and 'The Tale of the Fox' (1930)

- Later Russian fantasy films such as 'Alexander Nevsky' (1938) in their use of supernatural elements

- Soviet animated adaptations of folk tales

- Modern stop-motion films that use articulated puppets

- Contemporary Russian fantasy cinema's approach to folklore adaptation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived in a partially complete state through prints that were exported before the Russian Revolution. Several archives hold copies, including the Gosfilmofond in Russia and various European film archives. The film has undergone restoration efforts, though some sequences remain incomplete or damaged. The surviving prints show varying degrees of deterioration, with some animated sequences particularly affected by nitrate decomposition. Modern digital restoration has helped stabilize the surviving footage and enhance visibility of the stop-motion sequences. The film is considered an important artifact of early cinema and continues to be preserved as part of world film heritage.