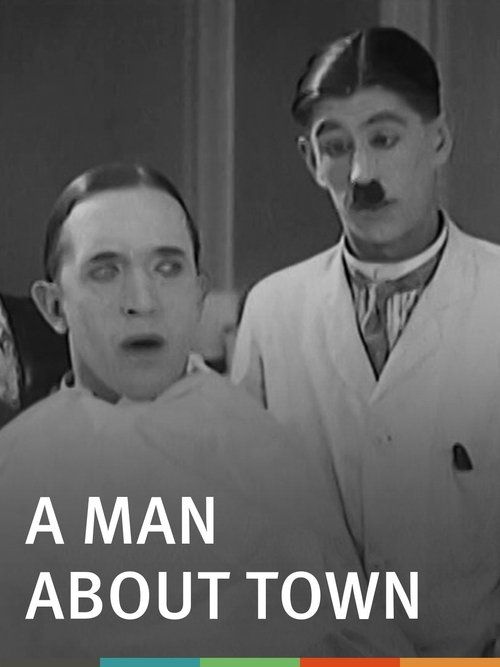

A Man About Town

Plot

In this silent comedy short, a young man portrayed by Stan Laurel finds himself in a predicament when he attempts to transfer from one streetcar to another but misses his connection. A helpful stranger suggests he follow a pretty young woman who supposedly knows the way to his destination. The young man obligingly follows her all over town, leading to a series of comedic situations as he trails her through various locations including shops, parks, and public buildings. His persistent following causes misunderstandings with other characters who mistake his intentions. The chase culminates in a chaotic finale where the young man finally realizes he's been led completely astray from his original destination.

About the Production

This was one of Stan Laurel's early solo comedy shorts before he formed his famous partnership with Oliver Hardy. The film was produced during the transition period when Laurel was establishing his comic persona in American cinema after moving from the UK. Like many shorts of this era, it was likely filmed quickly on existing studio sets and nearby locations to minimize costs.

Historical Background

1923 was a pivotal year in American cinema, as the film industry was consolidating its power in Hollywood and transitioning from short films to features. Comedy shorts remained extremely popular as part of theater programming, with studios like Hal Roach specializing in two-reel comedies. This period saw the refinement of comic archetypes and visual storytelling techniques that would define the silent comedy era. The film was made during the post-World War I economic boom when movie attendance was at an all-time high, and comedies particularly appealed to audiences seeking entertainment and escapism. The streetcar as a central plot device reflected the increasing urbanization of American life and the importance of public transportation in daily existence.

Why This Film Matters

While not a landmark film, 'A Man About Town' represents an important stage in Stan Laurel's career development before his immortal partnership with Oliver Hardy. The film exemplifies the typical comedy short format that dominated early 1920s cinema and served as training ground for comedy talent. The persistent following gag became a recurring trope in silent comedy, reflecting themes of urban confusion and romantic pursuit that resonated with contemporary audiences. The film also demonstrates the collaborative nature of early Hollywood comedy, where performers, directors, and supporting actors would work together repeatedly, refining their craft and developing the comic language that would influence generations of comedians.

Making Of

The production of 'A Man About Town' followed the typical rapid-fire schedule of comedy shorts in the early 1920s, often being completed in just a few days. Stan Laurel, having recently established himself in American comedy, was developing his screen character through these solo efforts. The collaboration with James Finlayson in this film marked an early connection before they would both become integral parts of the Laurel and Hardy team. The streetcar setting was practical for filming as it allowed for multiple gags and situations while using minimal set changes. Director George Jeske, who had experience as a comedian himself, understood the pacing and visual gags needed for successful silent comedy shorts.

Visual Style

The cinematography by the uncredited camera operator follows the standard practices for comedy shorts of the era, with clear, medium shots to capture physical comedy and facial expressions. The camera work emphasizes the visual gags and situational humor, with relatively static setups that allow the performers' movements to drive the comedy. The streetcar sequences likely employed practical location shooting mixed with studio work, creating a realistic urban environment while maintaining control over the comedic timing. The visual style prioritizes clarity and readability over artistic experimentation, ensuring audiences could easily follow the slapstick action.

Music

As a silent film, 'A Man About Town' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters, typically piano or organ. The score would have been compiled from standard photoplay music libraries, with selections matching the on-screen action - upbeat, playful music for the chase sequences, romantic themes when the young woman appeared, and frantic tempo during moments of confusion or slapstick. No original composed score was created specifically for this short, as was typical for productions of this scale and budget in 1923.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue quotes available)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening streetcar transfer sequence where Laurel misses his connection and receives the fateful advice to follow the young woman, setting up the entire comic premise of the film.

Did You Know?

- This film was released before Stan Laurel's legendary partnership with Oliver Hardy was formed in 1927

- James Finlayson, who appears in this film, would later become one of the most recognizable supporting actors in Laurel and Hardy comedies

- The film was produced by Hal Roach Studios, which would later become famous for the Laurel and Hardy films and Our Gang comedies

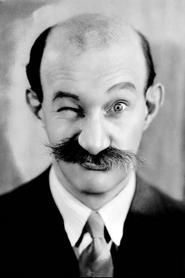

- Stan Laurel had already developed his distinctive screen persona by this time, though it would be further refined in his later films

- Katherine Grant was a frequent co-star with Laurel in his early solo films

- Like many silent shorts of the era, this film was likely shown as part of a larger program with other shorts and possibly a feature film

- The streetcar theme was a common comedic device in early 1920s films, as public transportation was a central part of urban life

- Director George Jeske was a former actor who transitioned to directing and worked extensively with comedy shorts

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of comedy shorts like 'A Man About Town' were typically brief, focusing on the entertainment value rather than artistic merit. Trade publications of the era generally praised Laurel's comic timing and the film's situational humor. Modern film historians view this early Laurel work as valuable for understanding his development as a comedian, though it's considered less sophisticated than his later Laurel and Hardy collaborations. The film is appreciated by silent film enthusiasts for its representation of early 1920s comedy style and its place in the evolution of American screen comedy.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1923 would have received this short as part of a typical theater program, appreciating its straightforward humor and visual gags. The following-the-girl premise was a familiar and popular comedy trope that guaranteed laughs. Stan Laurel's growing popularity as a solo comedian would have attracted viewers, and the film's urban setting would have resonated with contemporary moviegoers. Like most shorts of its era, it was designed for immediate entertainment rather than lasting impact, though Laurel's fans would have remembered it as part of his early American career.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Mack Sennett comedy shorts

- Chaplin's tramp character development

- Harold Lloyd's urban comedy style

This Film Influenced

- Later Laurel and Hardy following gags

- Similar streetcar comedies of the mid-1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'A Man About Town' is uncertain, as many silent comedy shorts from this period have been lost or exist only in incomplete copies. Some early Laurel solo films have survived through archives and private collections, but comprehensive documentation of this specific title's survival status is limited. The film may exist in film archives such as the Library of Congress or the Museum of Modern Art, or in private collector hands, but public access is likely restricted.