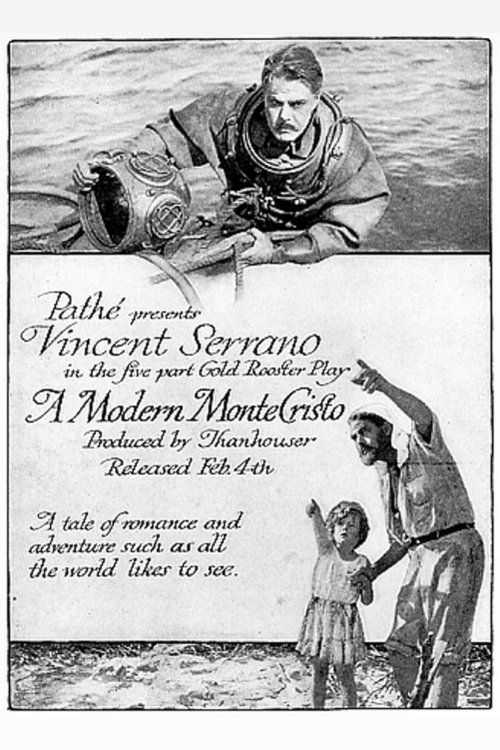

A Modern Monte Cristo

"A Tale of Vengeance and Love in the Twentieth Century"

Plot

In this contemporary adaptation of Alexandre Dumas's classic tale, a young sailor is wrongfully imprisoned after being falsely accused of a crime by his treacherous rival. After years of incarceration, he escapes and finds himself stranded on a remote desert island, where he discovers a fortune in pearl oysters. Using his newfound wealth, he returns to his hometown disguised as a wealthy gentleman, systematically orchestrating his revenge against those who betrayed him while protecting the woman he loves. The film transposes the 19th-century French setting to early 20th-century America, maintaining the core themes of betrayal, redemption, and justice while incorporating modern elements of the era.

About the Production

This film was one of Thanhouser's ambitious feature productions during their peak years. The desert island sequences were likely filmed on studio sets with painted backdrops, as was common for the era. The pearl diving scenes would have required underwater photography equipment, which was still experimental in 1917. Director Eugene Moore was one of Thanhouser's most reliable directors, known for his efficient work with limited resources.

Historical Background

1917 was a tumultuous year in American and world history. The United States entered World War I in April, just weeks after this film's release. The film industry was undergoing significant changes, with the Motion Picture Patent Company's monopoly crumbling and independent studios like Thanhouser thriving. The silent film era was at its zenith, with feature-length films becoming increasingly popular. This period also saw the rise of the 'feature film' as the dominant form of cinematic entertainment, replacing the earlier dominance of short subjects. The film's themes of justice and revenge resonated strongly with wartime audiences, who were dealing with the moral complexities of global conflict.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the early modern adaptations of a classic literary work, 'A Modern Monte Cristo' represents an important step in the evolution of cinema as a literary medium. The film demonstrates how early filmmakers were beginning to recognize the potential of adapting classic literature for contemporary audiences, a practice that would become a cornerstone of Hollywood production. The transposition of Dumas's 19th-century French setting to early 20th-century America reflects the growing American cultural confidence and the film industry's desire to make European stories accessible to domestic audiences. This approach to adaptation would influence countless future films and remains a common practice in contemporary cinema.

Making Of

The production took place at Thanhouser's state-of-the-art studio in New Rochelle, New York, which was considered one of the most advanced film production facilities of its time. Director Eugene Moore worked with a relatively small crew, typical of the era, with the cinematographer likely using natural light supplemented by arc lamps. The underwater sequences would have been particularly challenging to film in 1917, requiring specialized equipment and careful planning. The cast, led by the experienced Vincent Serrano, would have rehearsed extensively as retakes were expensive and time-consuming. The film's intertitles were likely written by Lloyd F. Lonergan, Thanhouser's primary scenario writer, who was known for his literary approach to screenwriting.

Visual Style

The cinematography would have been typical of Thanhouser's high standards for the period, featuring careful composition and effective use of lighting to create mood and atmosphere. The desert island sequences would have utilized painted backdrops and studio sets, while location shooting in the New York area would have provided authentic urban settings. The underwater pearl diving scenes, if they exist, would have been particularly innovative for 1917, requiring specialized equipment and techniques that were still experimental at the time.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film represented solid craftsmanship for its era. The underwater sequences, if indeed filmed rather than simulated, would have been technically ambitious for 1917. The film's five-reel length placed it among the growing number of feature films that were becoming the industry standard. Thanhouser's studio facilities were among the most advanced of their time, allowing for consistent lighting and production quality that elevated their films above many competitors.

Music

As a silent film, 'A Modern Monte Cristo' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The score would likely have been compiled from classical pieces and popular songs of the era, with specific musical cues provided by the studio for different emotional moments. Theatres of the time typically employed pianists or small orchestras, with larger venues offering more elaborate musical accompaniment. The music would have emphasized the film's dramatic moments, particularly during scenes of betrayal, escape, and revenge.

Famous Quotes

No specific quotes survive from this lost film, as intertitles from silent films are rarely preserved when the films themselves are lost

Memorable Scenes

- The desert island discovery of the pearl oysters

- The protagonist's return to his hometown in disguise

- The confrontation scenes with his betrayer

- The underwater pearl diving sequences

- The final revelation of the protagonist's true identity

Did You Know?

- This was one of numerous adaptations of Dumas's 'The Count of Monte Cristo' during the silent era, but one of the few that transposed the story to a contemporary setting

- Vincent Serrano, who played the lead, was a prominent stage actor before transitioning to films, bringing theatrical gravitas to the production

- Thanhouser Film Corporation was one of the pioneering American film studios, known for their high-quality productions despite modest budgets

- The film was released during World War I, a time when audiences were particularly drawn to tales of justice and redemption

- Director Eugene Moore directed over 100 films during his career, primarily for Thanhouser

- The pearl oyster element was a creative addition to modernize the source material and capitalize on the era's fascination with exotic wealth

- Helen Badgley was known as 'The Thanhouser Kid' and was one of the first child stars in American cinema

- The film's survival status is unknown, making it one of the many lost films from the silent era

- 1917 was a pivotal year in cinema, as feature films began to dominate over short subjects

- The Thanhouser studio was known for its progressive treatment of actors and relatively high production values for an independent studio

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from trade publications like The Moving Picture World and Variety praised the film's ambitious scope and the performances of its lead actors. Critics noted Vincent Serrano's commanding presence and Helen Badgley's natural charm. The film was generally regarded as a solid, if not spectacular, example of Thanhouser's production values. Modern critical assessment is impossible due to the film's apparent loss, but it would be valuable as an example of early American adaptation practices and the work of the often-overlooked Thanhouser studio.

What Audiences Thought

The film appears to have been moderately successful with audiences of its time, as evidenced by Thanhouser's continued production of feature films throughout 1917. Contemporary audiences would have been drawn to the familiar story and its modern setting, as well as the promise of exotic locations and dramatic revenge sequences. The film's release during wartime likely contributed to its appeal, as audiences sought escapist entertainment with moral clarity and satisfying resolutions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

- Contemporary American melodrama conventions

- Thanhouser's previous literary adaptations

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Monte Cristo adaptations throughout the silent and sound eras

- Modern-set literary adaptations by other studios

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Lost - No known copies of this film survive in any archive or private collection. Like approximately 75% of American silent films, it appears to be completely lost.