Aladdin and His Wonder Lamp

"The Marvelous Tale of Eastern Magic Brought to Life by the Cinematograph"

Plot

In this early cinematic adaptation of the classic Arabian Nights tale, a young and impoverished Aladdin discovers an ancient oil lamp containing a powerful genie. After rubbing the lamp and summoning the magical being, Aladdin uses his wishes to transform himself from a street urchin into a wealthy nobleman, winning the hand of the beautiful princess in marriage. However, an evil magician who originally tricked Aladdin into finding the lamp becomes consumed with jealousy and plots to steal the magical object for himself. When the magician successfully steals the lamp, he uses its power to abduct the princess and transport her to his distant kingdom, forcing Aladdin to embark on a perilous journey to recover the lamp and rescue his beloved wife. The film culminates in a magical confrontation between Aladdin and the sorcerer, where cleverness and true love triumph over greed and dark magic.

About the Production

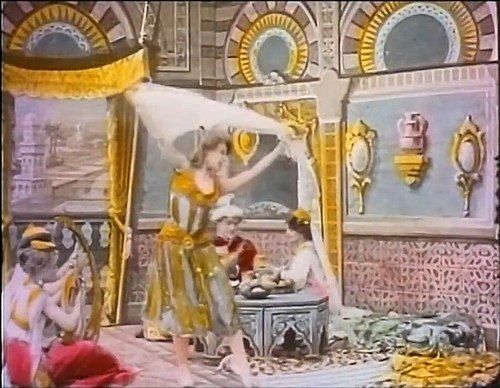

This film was created during the pioneering era of cinema when special effects were achieved through in-camera techniques, multiple exposures, and elaborate stage machinery. The magic lamp effects were likely created using substitution splicing and dissolves, while the genie's appearance would have been achieved through double exposure techniques. The sets were hand-painted backdrops typical of the period, with props and costumes designed to evoke an exotic Orientalist vision of the Middle East that was popular in European entertainment of the time.

Historical Background

The year 1906 represents a pivotal moment in early cinema, occurring just over a decade after the Lumière brothers' first public screening in 1895. During this period, cinema was rapidly evolving from simple novelty films and actualities to more complex narrative storytelling. The film industry was dominated by French companies, particularly Pathé Frères and Gaumont, which were producing and distributing films globally. This era saw the establishment of permanent movie theaters, the development of film distribution networks, and the beginning of cinema as a profitable entertainment industry. The Orientalist trend in European arts and literature was at its height, making stories like Aladdin particularly popular with audiences seeking exotic escapism. The film was created before the development of feature-length films, before the star system was established, and long before synchronized sound would revolutionize the medium.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest film adaptations of a story from 'One Thousand and One Nights,' this film represents an important milestone in bringing Eastern tales to Western audiences through the new medium of cinema. The film contributed to the popularization of Orientalist aesthetics in early cinema, establishing visual tropes and storytelling conventions that would influence countless subsequent adaptations of Middle Eastern stories. Its existence demonstrates how quickly filmmakers recognized cinema's potential for bringing magical and fantastical stories to life, using the medium's unique ability to create illusions through special effects. The film is historically significant as an example of how Pathé Frères helped establish the fantasy genre in cinema, and as part of the broader pattern of adapting literary works to the screen that would become fundamental to film history. Though largely forgotten today, it represents an important step in the development of narrative cinema and the fantasy film genre.

Making Of

The production of 'Aladdin and His Wonder Lamp' took place during a crucial period in cinema history when filmmakers were discovering the medium's potential for storytelling. Albert Capellani, working for the powerful Pathé company, was at the forefront of developing narrative techniques that would become standard in cinema. The film was shot on Pathé's studio sets using the primitive cameras of the era, which were large, hand-cranked devices that required considerable light. The magical effects were created entirely in-camera using techniques like multiple exposure, substitution splicing, and careful timing. The actors, drawn from theater and variety entertainment, had to adapt their performance style to the new medium, using exaggerated gestures and expressions to convey emotion without sound. The production would have been relatively quick by modern standards, likely completed in just a few days, as was typical for films of this length during the period.

Visual Style

The cinematography in this 1906 film would have employed the basic techniques available to filmmakers of the period. The camera would have been stationary, mounted on a tripod, as camera movement was not yet commonly practiced. Lighting would have been natural or basic studio lighting, requiring bright conditions for the slow film stock of the era. The visual style would have been theatrical, with compositions arranged like stage pictures. The special effects, achieved through in-camera techniques like multiple exposure and substitution splicing, would have been the most innovative aspects of the cinematography. The film likely employed the hand-coloring techniques that Pathé was pioneering at the time, with colors applied by hand to enhance the magical elements of the story.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievements lie in its early use of special effects to create magical illusions. The appearance of the genie would have been accomplished through multiple exposure techniques, while magical transformations would have used substitution splicing. These effects, while primitive by modern standards, were innovative for their time and demonstrated the creative possibilities of the new medium. The production likely employed Pathé's advanced stencil-coloring process for special releases, which was one of the earliest methods of adding color to motion pictures. The film also represents an early example of narrative storytelling techniques that were still being developed in cinema, including continuity editing and the use of intertitles to advance the plot.

Music

As a silent film, 'Aladdin and His Wonder Lamp' had no synchronized soundtrack. During exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in larger theaters. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or drawn from classical pieces and popular songs of the era, with the music chosen to match the mood and action of each scene. No specific musical score was composed for this film, as was standard practice for productions of this period. The experience of watching the film would have varied significantly depending on the quality of the musical accompaniment provided by each individual theater.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue survives as this is a silent film with no known intertitle text preserved

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Aladdin first discovers and rubs the magic lamp, causing the genie to appear in a puff of smoke using early special effects techniques

- The magical transformation of Aladdin from poverty to wealth, likely achieved through substitution splicing

- The confrontation between Aladdin and the evil magician, which would have featured the most elaborate special effects of the production

Did You Know?

- This film represents one of the earliest cinematic adaptations of the Aladdin story, predating the famous Disney version by over 85 years

- Director Albert Capellani was one of Pathé's most important early directors, known for his literary adaptations and innovations in narrative filmmaking

- The film was produced during cinema's transition from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narrative storytelling

- Liane de Pougy, who played the princess, was actually a famous Parisian courtesan and dancer before briefly appearing in films

- The special effects in this 1906 film were considered groundbreaking for their time, using techniques that would influence later fantasy films

- Like many films of this era, it was likely hand-colored frame by frame for special releases, with colors applied to enhance the magical elements

- The film was distributed internationally by Pathé, one of the world's first truly global film companies

- No complete original print is known to survive, making this one of the many lost films from cinema's first decade

- The role of Aladdin was played by Georges Vinter, who appeared in numerous Pathé productions during this period

- This film was part of Pathé's series of fairy tale and fantasy productions that were extremely popular with audiences worldwide

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of films in 1906 was limited, as film criticism as we know it today did not yet exist. Reviews, when they appeared, were typically brief mentions in trade publications or general newspapers. The film was likely well-received by audiences of the time, as fantasy and fairy tale adaptations were extremely popular in early cinema. Modern film historians view this work as an important example of early narrative filmmaking and the development of the fantasy genre, though its historical significance outweighs its artistic merit by contemporary standards. The film is studied today primarily for its historical value and as an example of early cinematic techniques rather than as a standalone artistic achievement.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1906 would have been captivated by the film's magical effects and exotic setting, as fantasy films were among the most popular genres of early cinema. The spectacle of a genie appearing from a lamp, magical transformations, and the romantic storyline would have provided the kind of escapist entertainment that drew people to the new medium of moving pictures. The film's Orientalist themes would have appealed to European audiences' fascination with the exotic East, a trend that was prevalent in literature, art, and popular entertainment of the period. Like most films of this era, it would have been shown as part of a varied program including newsreels, comedies, and other short subjects, with audiences paying for admission to an entire show rather than a single feature.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights)

- Stage adaptations of Aladdin stories popular in 19th century theater

- Georges Méliès' trick films and fantasy cinema

- Orientalist art and literature of the 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent silent film adaptations of Aladdin stories

- Later fantasy films featuring magical objects and genies

- The development of the fantasy genre in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered lost or partially lost, as no complete original print is known to survive. This is unfortunately typical of films from this early period of cinema. Fragments or incomplete versions may exist in film archives such as the Cinémathèque Française or the Library of Congress, but a complete, restored version is not available to modern audiences. The loss of this film represents part of the larger tragedy of early cinema history, where an estimated 75-90% of silent films have been lost due to the unstable nature of early film stock and lack of preservation efforts.