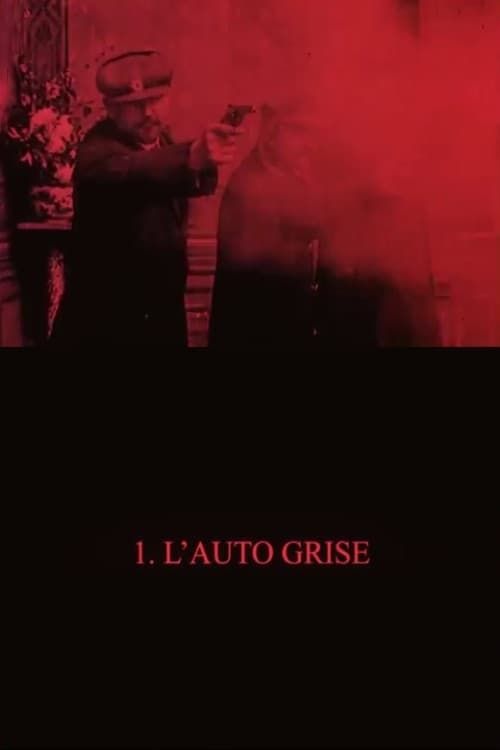

Bandits En Automobile - Episode 1: The Gray Car Gang

"Les bandits modernes qui défient la police avec leurs automobiles rapides"

Plot

The first episode of this pioneering crime serial follows a sophisticated gang of automobile bandits who terrorize the French countryside with their daring heists and high-speed getaways. Led by a mysterious mastermind, the Gray Car Gang utilizes the latest automotive technology to execute precision robberies, always escaping in their distinctive gray vehicle before authorities can respond. The film depicts their methodical planning and execution of a major bank robbery, showcasing their technical prowess and criminal ingenuity. As the gang's notoriety grows, law enforcement begins coordinating a massive dragnet to capture these modern criminals who represent a new threat to social order. The episode concludes with the gang successfully evading capture, setting the stage for their continued criminal spree in subsequent installments.

About the Production

The film was rushed into production immediately following the sensational real-life siege of the Bonnot Gang in April 1912, capitalizing on public fascination with the event. Director Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset employed actual automobiles and location shooting to enhance the film's realism and immediacy. The production faced challenges from French authorities who were concerned about the film's potential to glorify criminal behavior, leading to censorship in several cities. The film's innovative use of chase sequences and mobile camera work represented a significant advancement in action cinema techniques.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a period of tremendous social and technological change in France. The early 1910s saw the rise of automobile ownership, which created new opportunities for both legitimate business and criminal enterprise. The Bonnot Gang, led by Jules Bonnot, represented a new type of criminal - sophisticated, politically motivated, and technologically savvy. Their use of automobiles in crimes revolutionized law enforcement tactics and captured the public imagination. The gang's anarchist ideology and their dramatic confrontation with police at Choisy-le-Roi made them media sensations. This film emerged at a time when French cinema was transitioning from simple theatrical adaptations to more complex narrative forms that engaged with contemporary social issues. The film's production also coincided with the peak of the French film industry's global dominance, before World War I would dramatically alter the landscape of international cinema.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a crucial milestone in the development of the crime genre and the serial format in cinema. Its innovative use of contemporary events as source material established a template for future crime films and demonstrated cinema's power to engage with current social anxieties. The film's realistic depiction of modern criminal methods reflected growing public concerns about technology outpacing law enforcement capabilities. As one of the earliest films to feature automobile chase sequences, it pushed the boundaries of what was possible in action cinema. The film's prohibition in several cities also highlights the emerging debate about cinema's influence on society and the need for censorship. Its success in France helped establish the crime serial as a commercially viable genre, influencing countless subsequent films both in Europe and America. The film also represents an important example of early French cinema's sophistication and its willingness to tackle controversial subject matter.

Making Of

Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, already an established filmmaker by 1912, saw tremendous commercial potential in adapting the sensational Bonnot Gang story for the screen. He worked quickly to secure production resources from Éclair Studios, one of France's major film companies. The casting of Josette Andriot, a regular collaborator who had become one of France's first female action stars, brought star power to the production. The film crew faced significant challenges in staging the automobile chase sequences, as the vehicles of the era were difficult to control and the cameras were bulky and immobile. Jasset solved this by mounting cameras on moving platforms and using multiple cameras to capture the action from different angles. The production also had to contend with police surveillance, as authorities were concerned about the film's potential impact on public order. Despite these challenges, Jasset completed the film in record time, rushing it to theaters while the Bonnot Gang story was still fresh in the public consciousness.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Julien Ringel or another Éclair Studios cameraman featured innovative techniques for capturing motion and action. The film utilized mobile camera work to follow the automobile chases, a technical achievement for 1912 that required mounting cameras on moving platforms or vehicles. The filmmakers employed multiple camera setups to capture the action from various angles, creating a more dynamic visual experience than typical static shots of the era. The use of location shooting in actual urban and rural settings added to the film's realism and visual variety. The cinematography also made effective use of natural lighting and shadows to create atmosphere during the criminal sequences. The film's visual style reflected Éclair Studios' commitment to technical excellence and innovation, showcasing the company's ability to push the boundaries of what was cinematically possible.

Innovations

The film represented several technical innovations for its time, particularly in the realm of action cinematography. The successful capture of automobile chase sequences required the development of new camera mounting techniques and stabilization methods. The filmmakers employed early forms of editing rhythm to build tension during pursuit scenes, cutting between different perspectives to create a sense of movement and urgency. The production also demonstrated advances in location shooting techniques, proving that complex action sequences could be filmed outside the controlled environment of studio sets. The film's use of multiple camera setups for the same scene was particularly innovative, allowing for more sophisticated visual storytelling. These technical achievements helped establish new possibilities for action cinema and influenced subsequent developments in film language and technique.

Music

As a silent film, 'Bandits En Automobile' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The score would likely have been compiled from popular classical pieces and original compositions designed to enhance the film's dramatic moments. The automobile chase sequences would have been accompanied by fast-paced, rhythmic music to build tension and excitement, while quieter moments would have featured more subdued melodies. The musical accompaniment would have varied by theater, with larger cinemas employing full orchestras and smaller venues using piano or organ. The music would have played a crucial role in establishing the film's mood and helping audiences follow the narrative, particularly during the action sequences. Contemporary accounts suggest that some theaters even used sound effects such as automobile horns and police whistles to enhance the viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

Their gray car is like a phantom - here one moment, gone the next

In this new age, the criminal with an automobile is king of the road

The police may have numbers, but we have speed and cunning

Every bank vault is just a destination, and every road is our escape route

They call us bandits, but we are the future of crime

Memorable Scenes

- The opening bank robbery sequence showcasing the gang's methodical planning and execution

- The high-speed automobile chase through narrow Paris streets with police in pursuit

- The tense standoff where the gang uses their vehicle as a barricade against authorities

- The scene where the gang modifies their automobile with special equipment for their next crime

- The dramatic escape sequence where the gray car disappears into the countryside

Did You Know?

- The film was directly inspired by the real-life Bonnot Gang, a group of French anarchist illegalists who were among the first to use automobiles to escape from crime scenes

- Director Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset died just months after completing this film, making it one of his final works before his untimely death at age 51

- The film was banned or heavily censored in multiple French cities due to concerns it would inspire copycat crimes

- Josette Andriot, who starred in the film, was one of the earliest female action stars in cinema and frequently worked with Jasset

- The 'gray car' in the title was a deliberate reference to the actual vehicles used by the Bonnot Gang, which were typically luxury automobiles stolen from wealthy citizens

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of the crime serial genre, predating more famous American serials by several years

- The siege of Choisy-le-Roi that inspired the film involved over 500 police officers and military personnel and lasted for several hours

- The film's realistic depiction of criminal techniques led to it being studied by French law enforcement as a potential training tool

- Only fragments of this film are believed to survive today, as most of Jasset's work has been lost due to the fragility of early film stock

- The success of this film led to several sequels, though most are now considered lost films

What Critics Said

Contemporary French critics praised the film's technical innovation and its realistic portrayal of modern crime, though some expressed concern about its potential to glamorize criminal behavior. Le Film journal noted the film's 'remarkable cinematographic ingenuity' in capturing the automobile sequences, while Ciné-Journal highlighted its 'dramatic intensity and contemporary relevance.' Critics recognized Jasset's skill in transforming recent news events into compelling cinema. Modern film historians view the work as a significant achievement in early crime cinema, though they note that its full impact is difficult to assess due to the film's partially lost status. The film is now recognized as an important precursor to the gangster film genre and a key work in Jasset's oeuvre, demonstrating his ability to combine commercial appeal with artistic innovation.

What Audiences Thought

The film generated tremendous public interest upon its release, drawing large audiences eager to see a cinematic version of the sensational Bonnot Gang story. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly thrilled by the automobile chase sequences, which represented a novel form of cinematic excitement. The film's prohibition in several cities only increased its notoriety and appeal, with some viewers traveling to neighboring towns to see the controversial production. Working-class audiences reportedly identified with the film's anti-authoritarian themes, while middle-class viewers were drawn to its sophisticated technical elements. The film's success led to increased demand for crime serials and established a template for future productions that would blend contemporary events with dramatic storytelling. Audience enthusiasm for the film was so strong that it spawned several sequels, though most of these subsequent works are now lost.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The real-life Bonnot Gang crimes and siege

- Earlier French crime serials like 'Nick Carter'

- Contemporary newspaper accounts of automobile crimes

- Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset's previous work in the crime genre

- Popular French crime literature of the early 1910s

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent French crime serials of the 1910s

- American gangster films of the 1920s and 1930s

- Later automobile chase films

- Modern crime procedural television series

- Contemporary heist films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments and individual sequences surviving in various film archives. The Cinémathèque Française holds some footage, as does the British Film Institute. Complete copies are believed to no longer exist, making it one of the many casualties of early cinema's preservation challenges. The surviving fragments suggest the film's technical sophistication but provide only a partial view of Jasset's complete vision. Film historians continue to search for additional footage in private collections and lesser-known archives.