Barney Oldfield's Race for a Life

"The Greatest Race Driver in the World in a Race for a Life!"

Plot

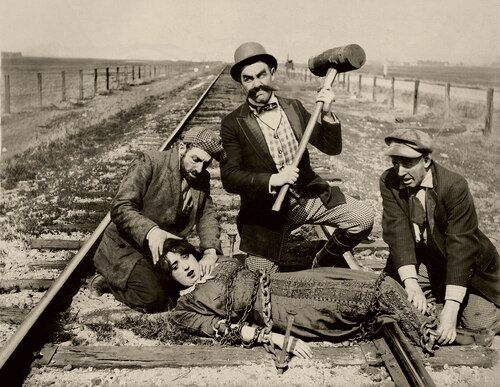

In this classic Keystone comedy, a villainous character played by Ford Sterling becomes enraged when Mabel Normand rejects his romantic advances. In a fit of jealous rage, he ties her to the railroad tracks, leaving her to face an approaching train. Her bashful suitor, played by Mack Sennett, realizes he cannot save her alone and desperately seeks help from the famous real-life racecar driver Barney Oldfield. The film culminates in a thrilling race against time as Oldfield speeds to rescue Mabel in his racing car, creating a spectacular chase sequence that combines comedy with genuine suspense.

Director

About the Production

This film was one of the earliest examples of celebrity crossover in cinema, featuring real racecar driver Barney Oldfield as himself. The production utilized actual racing cars and railroad tracks, creating authentic action sequences. The film was shot in a single day, typical of Keystone's rapid production schedule, with minimal script and heavy reliance on improvisation and physical comedy.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in American cinema history, when the industry was transitioning from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. 1913 was the year before the outbreak of World War I, a period of rapid technological advancement and social change in America. The automobile was still a relatively new invention, and racecar drivers like Barney Oldfield were considered modern heroes, embodying the speed and excitement of the new industrial age. The film also emerged during the height of the Progressive Era, when audiences were hungry for entertainment that reflected the dynamic changes in American society.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest examples of celebrity crossover in cinema, paving the way for future athlete-actor collaborations. It also represents a crucial moment in the development of American comedy, demonstrating how parody could be used to satirize contemporary entertainment trends. The film's success helped establish the template for action-comedy that would dominate Hollywood for decades. Additionally, it captured the American fascination with speed and technology during the early automotive age, making it a valuable cultural document of the era's values and interests.

Making Of

The production of 'Barney Oldfield's Race for a Life' exemplified the Keystone Studios philosophy of rapid, energetic filmmaking. Mack Sennett discovered Barney Oldfield at a racing event and immediately conceived the idea of featuring him in a film. The railroad sequence was particularly challenging to film, requiring careful coordination between the actors, the train operator, and Oldfield's racing car. Mabel Normand, who was Sennett's romantic partner both on and off screen, performed her own stunts, including being tied to the tracks. The film's success was largely due to the authentic presence of Oldfield, whose natural charisma translated well to the screen despite having no acting experience.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Keystone productions of the era, was straightforward but effective in capturing the fast-paced action. The camera work during the racing sequences was particularly noteworthy for its time, using tracking shots to follow Oldfield's car. The railroad track scene utilized multiple camera angles to build tension, including close-ups of Mabel's terrified expression and wide shots showing the approaching train. The film's visual style emphasized clarity and action over artistic experimentation, reflecting the studio's focus on entertainment value.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its successful integration of real racing footage with narrative storytelling. The production team developed innovative camera mounting techniques to capture the speed of Oldfield's car without endangering the equipment. The railroad sequence required precise timing and coordination between multiple elements, demonstrating sophisticated planning for a 1913 production. The film also pioneered the use of celebrity authenticity in fictional narratives, a technique that would become increasingly important in film marketing.

Music

As a silent film, 'Barney Oldfield's Race for a Life' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. Typical theater orchestras or pianists would have provided appropriate musical accompaniment, likely including popular songs of the era and classical pieces adapted for action sequences. The racing scenes would have been accompanied by fast-paced, energetic music, while the romantic moments would have featured more melodramatic themes. No original composed score exists for the film, as was standard practice for productions of this period.

Famous Quotes

Help! Barney Oldfield! Save me!

The fastest man on Earth must save the woman I love!

No train can beat my racing car!

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic race sequence where Barney Oldfield speeds along the railroad tracks in his racing car to rescue Mabel, with the train visible in the background, creating genuine tension and excitement for 1913 audiences.

Did You Know?

- Barney Oldfield was one of the most famous racecar drivers of his era, known for being the first person to drive a mile a minute in 1903

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of a celebrity athlete appearing in a motion picture

- The railroad track scene was a parody of the overly dramatic melodramas popular at the time

- Mack Sennett not only directed and starred in the film but also founded Keystone Studios

- The film was released during the golden age of silent comedy and helped establish many tropes that would become standard in the genre

- Barney Oldfield was paid $500 for his appearance, a substantial sum for 1913

- The racing car used in the film was Oldfield's actual racing vehicle, a Knox

- This was one of the first films to feature a real automobile in a central role

- The film's success led to several other collaborations between Keystone and celebrity athletes

- The railroad track sequence was filmed on an actual disused railway line near Keystone Studios

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its innovative use of a real celebrity and its thrilling action sequences. The Motion Picture World noted that 'the presence of the famous Barney Oldfield adds a special thrill to this Keystone production.' Modern film historians recognize it as a significant early example of the action-comedy genre and an important milestone in the development of American cinema. Critics today appreciate the film's self-aware parody of melodramatic tropes and its role in establishing Keystone's distinctive comedic style.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences of 1913, who were thrilled to see the famous racecar driver on screen. The combination of comedy, romance, and genuine suspense proved to be a winning formula. Contemporary reports indicate that theaters showing the film experienced increased attendance, particularly among young male audiences who admired Oldfield. The film's success at the box office demonstrated the commercial viability of featuring real celebrities in fictional narratives, a strategy that would become increasingly common in Hollywood.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Contemporary stage melodramas

- D.W. Griffith's Biograph shorts

- European comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Keystone Cops series

- Later Charlie Chaplin comedies

- Buster Keaton's The General (1926)

- Harold Lloyd's speed-themed comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by several film archives. While not considered lost, some sequences show signs of deterioration typical of nitrate film from this era. The film is available through various archival sources and has been included in several collections of early American cinema.