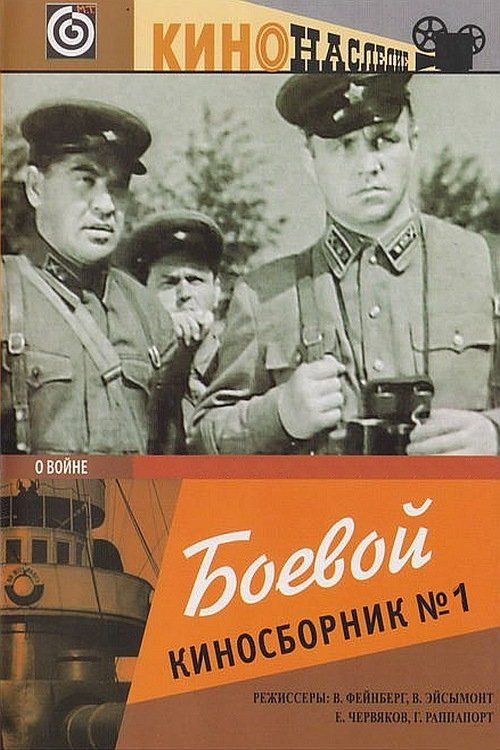

Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #1

Plot

Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #1 is a 1941 Soviet propaganda anthology film consisting of three patriotic novellas created to boost morale during the early days of World War II. The first segment 'Meeting with Maxim' features the hero from the film 'Vyborg Side' breaking the fourth wall to deliver a passionate patriotic appeal directly to the audience. The second segment 'A Dream in the Hand' presents a satirical nightmare sequence where Hitler dreams of his inevitable defeat on Russian soil, haunted by visions of Napoleon and German occupiers from 1918 who previously experienced Russian military might. The third segment 'Three in a funnel' depicts a wounded Red Army soldier and a nurse sharing a bomb crater with an injured Hitler, where the nurse's humanitarian gesture is repaid with betrayal, leading to the Nazi's defeat by the Soviet soldier's precise shot.

About the Production

This film was produced as part of a series of propaganda shorts specifically designed for distribution to Soviet armed forces during the early months of the Great Patriotic War. The production was rushed to completion following the Nazi invasion of June 1941, with the film serving as immediate wartime propaganda to boost morale and demonize the enemy. The anthology format allowed for multiple patriotic messages to be delivered in a single screening, maximizing the impact of limited wartime film resources.

Historical Background

Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #1 was produced in July 1941, immediately following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. This period marked the beginning of what the Soviets called the Great Patriotic War, and the film represents one of the earliest cultural responses to the invasion. The Soviet Union was experiencing devastating losses in the early months of the war, with German forces advancing rapidly toward Moscow. The film industry, like all sectors of Soviet society, was mobilized for total war, with filmmakers tasked with creating content that would boost morale, demonize the enemy, and rally support for the war effort. The anthology format and direct messaging reflect the urgent need for effective propaganda during this crisis period. The film's themes of inevitable victory and Russian strength in the face of invasion drew on historical parallels to Napoleon's 1812 invasion, which was being actively promoted by Soviet propaganda as a precedent for eventual victory.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of Soviet wartime propaganda cinema and the immediate cultural response to the Nazi invasion. As part of the first wave of wartime films, it helped establish the narrative framework that would dominate Soviet cinema throughout World War II. The film's use of established characters like Maxim connected the new wartime struggle to pre-war Soviet heroic narratives, creating continuity in the face of disruption. The satirical portrayal of Hitler and the emphasis on inevitable defeat contributed to the broader Soviet propaganda campaign that maintained morale during the darkest days of the war. The anthology format influenced subsequent wartime film production, demonstrating the efficiency of multiple short narratives for conveying propaganda messages. The film also exemplifies the Soviet practice of breaking the fourth wall to directly address audiences, a technique that would become common in wartime cinema.

Making Of

The production of Collection of Films for the Armed Forces #1 occurred under extreme pressure following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. The film industry was immediately mobilized for war effort, with directors, writers, and actors working around the clock to create content that would support the war effort. Director Yevgeniy Nekrasov, known for his documentary background, brought a sense of immediacy and authenticity to the propaganda pieces. The casting of established actors like Pyotr Repnin helped connect the new wartime messaging to familiar patriotic narratives from pre-war cinema. The third segment's bomb crater was likely a constructed set designed to realistically depict battlefield conditions while allowing for controlled filming. The production team worked with limited resources as many film industry professionals had been conscripted and equipment was being repurposed for military use.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed straightforward, documentary-style techniques appropriate for propaganda filmmaking. The first segment used conventional framing for the patriotic address, with direct camera angles creating intimacy between the character and audience. The dream sequence in the second segment likely employed expressionistic lighting and distorted perspectives to create the nightmarish atmosphere. The bomb crater setting in the third segment would have used low-angle shots to emphasize the claustrophobic conditions and dramatic tension. The visual style prioritized clarity of message over artistic experimentation, ensuring the propaganda content was easily understood by all viewers. The black and white cinematography emphasized the moral clarity of the narrative, with stark contrasts between heroic Soviet characters and villainous Nazis.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its rapid production and release under wartime conditions. The anthology format demonstrated an efficient approach to creating multiple propaganda narratives within a single production. The film's use of breaking the fourth wall was innovative for Soviet cinema of the period and proved effective for direct propaganda messaging. The practical effects for the bomb crater setting would have required careful construction to appear realistic while allowing for camera movement and actor performance. The film's distribution system to armed forces represented an achievement in wartime logistics, ensuring the content reached its intended military audience despite the chaos of the early invasion period.

Music

The musical score likely featured patriotic Soviet songs and martial themes appropriate for wartime propaganda. The soundtrack would have included dramatic musical cues to emphasize emotional moments, particularly during the patriotic addresses and the climactic confrontation in the third segment. The music probably incorporated familiar Soviet patriotic melodies that would resonate with contemporary audiences. Sound effects would have been used to enhance the realism of the battle scenes and the dramatic impact of the final shot. The audio design prioritized clarity of dialogue to ensure the propaganda messages were clearly communicated to military audiences who might be viewing the film under less-than-ideal conditions.

Famous Quotes

From the first segment: 'Comrades! The enemy is at our gates, but the Russian spirit has never been broken and never will be!'

From the dream sequence: 'Even in your dreams, Hitler, you cannot escape the power of Russian arms!'

From the third segment: 'A Soviet soldier never misses when defending his Motherland!'

Memorable Scenes

- The breaking of the fourth wall in 'Meeting with Maxim' where the hero steps out of the film to directly address the audience with patriotic fervor

- The satirical dream sequence where Hitler is tormented by visions of defeated invaders throughout Russian history

- The dramatic confrontation in the bomb crater where the wounded Red Army soldier saves the nurse from Hitler's betrayal

Did You Know?

- The film was created and released within weeks of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, making it one of the earliest Soviet propaganda responses to Operation Barbarossa

- The character Maxim in the first segment references the popular 1939 film 'Vyborg Side', creating continuity with established Soviet cinema heroes

- The third segment's bomb crater setting was likely inspired by real wartime conditions that Soviet soldiers and civilians were experiencing

- Director Yevgeniy Nekrasov specialized in documentary and propaganda films, bringing a realistic approach to the wartime messaging

- The film was part of a numbered series intended for armed forces distribution, suggesting multiple similar collections were planned

- The satirical portrayal of Hitler in the second segment was part of a broader Soviet campaign to humanize the enemy's inevitable defeat

- The nurse character in the third segment represents Soviet compassion and humanitarianism, contrasting with Nazi brutality

- The film's anthology format was efficient for wartime production, allowing multiple messages to be filmed quickly with limited resources

- Pyotr Repnin, who played Maxim, was a prominent Soviet actor known for his roles in patriotic films

- The film's release timing coincided with some of the darkest days of the early war, when Soviet forces were retreating and morale was desperately needed

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its timely patriotic messaging and effectiveness as wartime propaganda. Reviews in Soviet film journals emphasized the film's role in boosting morale and its clear anti-fascist stance. The direct address to the audience in the first segment was particularly noted as an innovative technique for engaging viewers. The satirical elements were appreciated for providing emotional release through humor while maintaining the serious patriotic message. Post-war Soviet film historians recognized the collection as an important example of early wartime cinema that helped establish the visual and narrative language of Soviet propaganda films. Western film scholars have studied the collection as an example of how the Soviet film industry rapidly adapted to wartime conditions and the immediate mobilization of cinema for propaganda purposes.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Soviet audiences in 1941, particularly by military personnel for whom it was primarily intended. Soldiers and civilians facing the early German onslaught found reassurance in the film's confident message of inevitable victory. The direct address format created a sense of personal connection with the patriotic messaging. The satirical portrayal of Hitler provided emotional satisfaction and comic relief during a period of extreme stress and uncertainty. The clear moral narrative of good versus evil resonated with audiences experiencing the reality of invasion. The film's distribution to armed forces meant it reached viewers at a time when they most needed moral support and reassurance. Contemporary accounts suggest the film was effective in its intended purpose of boosting morale and reinforcing the resolve to fight the invaders.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realism

- Pre-war Soviet patriotic cinema

- Documentary filmmaking techniques

- Political propaganda traditions

- Historical war narratives

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Soviet wartime propaganda films

- Later anthology films for military audiences

- Post-war Soviet films about the Great Patriotic War

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond) and has been digitized as part of Soviet wartime film preservation efforts. While not widely available commercially, it exists in archival collections and has been shown in retrospective screenings of Soviet propaganda cinema. The film's historical significance has ensured its preservation despite its obscure status.