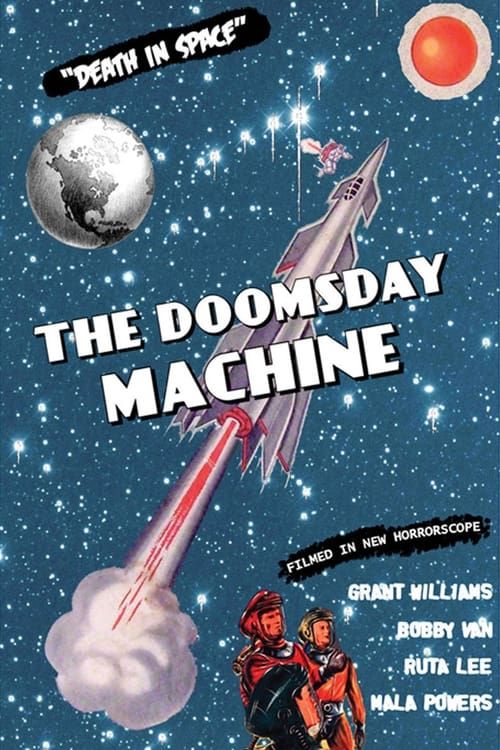

Doomsday Machine

"The Ultimate Weapon of Destruction!"

Plot

When scientists discover a massive doomsday machine orbiting Earth capable of destroying the planet, the United States hastily prepares a space mission to Venus as a last-ditch effort to preserve humanity. The seven-person crew, consisting of four male astronauts and three female scientists, launches aboard the spaceship Astra, only to have their mission suddenly taken over by the military who reveals a darker purpose. As they journey through space, the crew discovers they are part of a secret military plan to use Venus as a staging ground for a counterattack against the alien device. Tensions mount as the crew members grapple with the military takeover, their personal relationships, and the realization that Earth's fate may already be sealed. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation between the military's aggressive approach and the scientists' more measured response to the existential threat facing humanity.

About the Production

The film was actually shot in 1967 under the title 'Space Flight' but remained unreleased for five years until Crown International Pictures acquired it and released it in 1972 as 'Doomsday Machine'. The production was notoriously troubled with incomplete special effects that were later filled in with stock footage and additional scenes shot years later. Some cast members had significantly aged between the original 1967 shoot and the 1972 pickup shots, creating noticeable continuity issues.

Historical Background

Released in March 1972, 'Doomsday Machine' emerged during a period of heightened Cold War tensions and growing public anxiety about nuclear annihilation. The early 1970s saw the continuation of the Vietnam War, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) between the US and Soviet Union, and increasing environmental concerns. The film's themes of technological destruction and military overreach resonated with audiences living under the threat of nuclear war. The space race, which had dominated the 1960s, was transitioning from competition to cooperation with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project being planned. Science fiction cinema was also evolving, moving from the optimistic visions of the 1960s toward more dystopian and cautionary tales in the 1970s, exemplified by films like 'THX 1138' (1971) and 'Silent Running' (1972). The film's delayed release from 1967 to 1972 also meant it captured the changing attitudes toward authority and technology that characterized the late 1960s and early 1970s counterculture movement.

Why This Film Matters

While not a critical or commercial success, 'Doomsday Machine' represents a transitional moment in American science fiction cinema, bridging the gap between the space-race optimism of the 1960s and the darker, more paranoid sci-fi of the 1970s. The film's depiction of military takeover of a scientific mission reflected growing public distrust of authority during the Vietnam War era. Its portrayal of an all-male military command structure clashing with civilian scientists anticipated themes that would become more prominent in later science fiction works. The film also exemplifies the exploitation film approach to science fiction, where serious themes were packaged with sensational elements to attract drive-in audiences. Despite its low budget and technical limitations, the film's very existence demonstrates how science fiction served as a vehicle for exploring contemporary anxieties about technology, warfare, and human survival during a turbulent period in American history.

Making Of

The production of 'Doomsday Machine' was notoriously troubled, beginning as a straightforward space exploration film called 'Space Flight' in 1967. Director Lee Sholem shot the principal photography with a modest budget and limited resources, utilizing existing studio sets and minimal special effects. The original production ran out of money before completion, leaving the film unfinished in a studio vault for several years. In 1971, Crown International Pictures acquired the footage and decided to complete it by adding new scenes with different actors to create a more marketable science fiction thriller. This resulted in the military takeover subplot and the doomsday machine premise being grafted onto the original material. The patchwork nature of the production is evident throughout the film, with noticeable differences in film quality, actor appearances, and set design between the 1967 and 1972 footage. The special effects team was forced to work with extremely limited resources, often using stock footage from other science fiction productions and creating effects with household items and simple lighting techniques.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by William H. Clothier for the 1967 footage and unknown cinematographers for the 1972 additions, reflects the film's troubled production history. The original 1967 material shows competent, if unremarkable, cinematography typical of television production of the era, with standard lighting and composition for the spaceship interiors. The 1972 footage exhibits a different visual style, with harsher lighting and more dynamic camera movements that create jarring inconsistencies when intercut with the earlier material. The space sequences rely heavily on stock footage from other productions, resulting in noticeable shifts in visual quality and style. The film makes extensive use of colored gels and practical lighting effects to create the illusion of advanced technology, with red and blue lighting frequently employed to indicate different ship systems or emergency conditions. The cinematography's most notable achievement is its successful creation of claustrophobic tension within the limited spaceship sets, using tight framing and low angles to enhance the sense of confinement.

Innovations

As a low-budget production, 'Doomsday Machine' achieved little in terms of technical innovation, instead relying on established techniques and creative problem-solving. The film's spaceship sets were constructed using modular components that could be reconfigured to represent different areas of the vessel, a cost-effective approach that had been used in television science fiction since the 1950s. The special effects team employed forced perspective and mirror techniques to create the illusion of larger spaces within the confined studio sets. The doomsday machine itself was created using a combination of practical effects, including a motorized disc with attached lights and smoke effects to suggest its destructive capabilities. The film's most notable technical achievement was its successful integration of footage from multiple sources shot years apart, creating a coherent if imperfect narrative. The production team also developed creative solutions for the zero-gravity sequences, using wires and careful camera angles to simulate weightlessness within their limited budget constraints.

Music

The musical score was composed by Paul Sawtell and Bert Shefter, veteran film composers who had worked on numerous science fiction and horror films. Their score combines traditional orchestral elements with electronic sounds to create a space-age atmosphere that was becoming standard for the genre in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The main theme features a dramatic brass melody accompanied by electronic oscillations, while the underscore makes extensive use of tremolo strings and low-frequency electronic pulses to maintain tension during space sequences. The soundtrack also incorporates stock music cues from other productions, another cost-saving measure common in low-budget films of the era. Sound effects were created using a combination of standard foley techniques and electronic manipulation, with the doomsday machine itself being represented by a series of descending electronic tones and mechanical grinding sounds. The audio quality varies noticeably between the 1967 and 1972 footage, with the earlier material having cleaner sound reproduction than the later additions.

Famous Quotes

General: 'Gentlemen, we're not going to Venus to explore. We're going there to survive!'

Dr. Marion: 'Science without conscience is the death of the soul.'

Major Mason: 'In a crisis, democracy is a luxury we cannot afford.'

Danny: 'Space doesn't care about our politics. It only cares about our physics.'

Captain: 'The doomsday machine doesn't negotiate. It only eliminates.'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic military takeover scene where armed soldiers board the spaceship and reveal the true mission to the shocked crew

- The zero-gravity love scene between two crew members, achieved with visible wires and awkward slow-motion photography

- The final confrontation with the doomsday machine, featuring the spinning disc with Christmas lights and smoke machine effects

- The scene where the crew discovers the government's secret plans through intercepted communications

- The opening sequence showing the discovery of the doomsday device orbiting Earth

Did You Know?

- The film was shot in 1967 but not released until 1972, making it one of the longest-delayed releases of its era

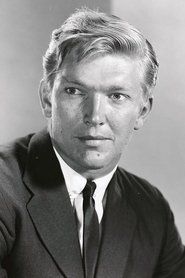

- Director Lee Sholem was primarily known for directing Superman TV episodes and low-budget films

- The spaceship sets were recycled from other productions and were visibly showing their age

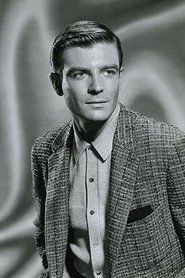

- Grant Williams, who plays Major Kurt Mason, was famous for starring in 'The Incredible Shrinking Man' (1957)

- The film features an early appearance by James Hong, who would later become a prolific character actor

- Some scenes were shot without sound and later dubbed, creating noticeable lip-sync issues

- The 'doomsday machine' itself was created using minimal special effects, primarily consisting of a spinning metal disc with lights

- The film's release capitalized on the early 1970s science fiction boom following the success of '2001: A Space Odyssey'

- Crown International Pictures, the distributor, specialized in releasing low-budget exploitation films

- The original cut reportedly ran over two hours but was heavily edited down for release

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was overwhelmingly negative, with most reviewers dismissing the film as a poorly executed exploitation picture. Critics noted the obvious production problems, including mismatched footage, poor special effects, and incoherent plotting resulting from the film's patchwork production history. The Los Angeles Times called it 'a confusing mess of stock footage and amateurish effects' while Variety noted that 'the five-year delay between filming and release shows in every frame'. Modern reassessments by cult film enthusiasts have been somewhat more charitable, acknowledging the film's place in the pantheon of 1970s drive-in cinema and finding value in its unintentional humor and period charm. Some retro sci-fi reviewers have pointed out that despite its technical flaws, the film does attempt to address serious themes about the military-industrial complex and the dangers of unchecked technological power.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was modest, with the film primarily finding its audience at drive-in theaters and grindhouse venues where low-budget science fiction films were part of double and triple bills. The film's exploitation elements, including the presence of multiple female crew members and hints at sexual tension in space, were marketed heavily in promotional materials. Over time, the film has developed a small cult following among enthusiasts of bad cinema and 1970s science fiction. Modern audiences often discover the film through midnight screenings or home video releases specializing in cult and exploitation films. The film's technical shortcomings and unintentionally humorous moments have made it a favorite among fans of 'so bad it's good' cinema, with some viewers appreciating it as a time capsule of early 1970s genre filmmaking.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

- Planet of the Vampires (1965)

- Star Trek (television series)

- The Twilight Zone (television series)

- Forbidden Planet (1956)

This Film Influenced

- Future War (1997)

- The Doomsday Machine (2008 documentary)

- Various low-budget sci-fi films of the 1970s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in multiple 35mm release prints and has been preserved through various home video releases. While no official restoration has been undertaken by major film archives, the movie has entered the public domain in some territories, leading to numerous DVD and digital releases of varying quality. The original camera negative status is unknown, but complete versions of the theatrical cut are readily available through specialty labels and public domain distributors. Some versions circulating online contain additional scenes not present in the original theatrical release, likely sourced from workprint materials.