Départ en voiture

Plot

This brief documentary captures a simple yet significant moment of daily life in late 19th century France. Three elegantly dressed women approach a horse-drawn carriage and prepare for departure as servants carefully load luggage onto the roof of the vehicle. The women enter the carriage one by one, arranging themselves comfortably for the journey ahead. Once everyone is settled and the luggage is secured, the carriage driver gives the signal and the vehicle begins to move away from the camera, disappearing down the road. The entire scene is captured in a single, continuous shot that lasts approximately 45 seconds, exemplifying the Lumière brothers' fascination with documenting real, unscripted moments of everyday life.

About the Production

Filmed using the Lumière Cinématographe, which served as both camera and projector. The film was shot outdoors in natural light, a common practice for early Lumière productions. The cast consisted of family members and acquaintances of the Lumière family, typical of their early films which often featured non-professional actors from their immediate circle. The carriage and horses were likely borrowed from a local livery service or owned by someone in the community.

Historical Background

1895 was a pivotal year in human history, marking the birth of cinema as both a technology and an art form. The Lumière brothers, Louis and Auguste, had just perfected their Cinématographe device, which was superior to Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope because it allowed projection to an audience rather than individual viewing. This film was created during the Belle Époque period in France, a time of great technological innovation, artistic flourishing, and social change. The industrial revolution had transformed transportation, making horse-drawn carriages common among the middle and upper classes, which this film documents. The December 28, 1895, screening where this film premiered is widely considered the birth of commercial cinema, charging admission for the first time in history. This was also the year of the first modern Olympic Games, the discovery of X-rays, and the publication of H.G. Wells' 'The Time Machine', placing cinema among the major innovations of the age.

Why This Film Matters

'Départ en voiture' represents a crucial milestone in the development of cinema as a medium for capturing and preserving everyday life. As one of the first motion pictures ever shown to a paying audience, it helped establish the fundamental language of cinema, including the concept of the moving image as a form of entertainment and documentation. The film exemplifies the Lumière brothers' philosophy that cinema's greatest value lay in its ability to capture reality, a perspective that influenced documentary filmmaking for generations to come. It also demonstrates how early cinema served as a time capsule, preserving details of 19th-century life, from clothing styles to social customs and transportation methods. The inclusion of servants loading luggage while their employers wait provides insight into the class structure of the period. This film, along with other Lumière productions, helped establish France as the birthplace of cinema and set the template for the actuality film genre that would become a cornerstone of documentary filmmaking.

Making Of

The filming of 'Départ en voiture' took place during the Lumière brothers' most productive period in 1895, when they were actively creating content for their new invention. The scene was likely staged but captured in a single take to maintain the appearance of natural, unscripted reality. The location in La Ciotat was chosen because it was near the Lumière family's summer home, providing convenient access for filming. The cast consisted of family members and friends, with Marguerite Lumière (the brothers' mother) and other female relatives playing the roles of the departing travelers. The servants shown loading the luggage were likely actual household staff or local workers hired for the occasion. The entire production would have been completed in a matter of minutes, as the early Cinématographe cameras could only film for about 50 seconds before needing to be reloaded.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Départ en voiture' is characterized by its stationary camera position and single, uninterrupted take, typical of early Lumière productions. The camera was mounted on a tripod at approximately eye level, capturing the scene from a fixed perspective that allows viewers to observe the action as if they were standing nearby. The natural lighting creates authentic shadows and highlights, giving the image a documentary quality that was central to the Lumière aesthetic. The composition balances the human subjects with the carriage and surrounding environment, creating a harmonious frame that tells a complete story without camera movement. The depth of field captures both foreground and background elements clearly, allowing viewers to see the details of the servants' work as well as the women's interactions. The black and white imagery, while a technical limitation of the period, adds to the film's historical authenticity and timeless quality.

Innovations

'Départ en voiture' showcases several groundbreaking technical achievements that were revolutionary for their time. The film was shot using the Lumière Cinématographe, a remarkable device that functioned as camera, developer, and projector all in one portable unit. The camera used a claw mechanism to advance the film intermittently, creating smoother motion than earlier devices. The film was shot at approximately 16 frames per second, which became the standard for silent films. The 35mm film format used established a standard that would dominate cinema for decades. The camera's hand-crank operation allowed for precise control over exposure time, while its relatively light weight (about 5 kg) made outdoor filming practical. The projection system used a powerful lamp and lens to throw a bright image onto a screen, allowing the film to be viewed by large audiences simultaneously - a significant improvement over Edison's individual viewing devices.

Music

As a silent film from 1895, 'Départ en voiture' was originally presented without any synchronized soundtrack. During its initial screenings at the Salon Indien du Grand Café, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist playing appropriate mood music to enhance the viewing experience. The musical accompaniment likely consisted of popular light classical pieces or improvised melodies that matched the gentle, observational nature of the film. Some venues might have employed small ensembles with violin, cello, and piano to provide a more sophisticated musical backdrop. Modern presentations of the film sometimes feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to recreate the authentic silent film experience. The absence of recorded sound emphasizes the visual nature of the work and forces viewers to focus on the subtle movements and interactions captured in the frame.

Memorable Scenes

- The final moment when the carriage pulls away from the camera and disappears down the road, creating a sense of movement and departure that must have been magical to 1895 audiences

Did You Know?

- This film was part of the historic first public screening of motion pictures on December 28, 1895, at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris

- The film runs for only 45 seconds, which was typical of early Lumière productions

- It was one of ten films shown at the groundbreaking first public screening that launched cinema as a commercial enterprise

- The film demonstrates the Lumière brothers' preference for actuality films over staged narratives

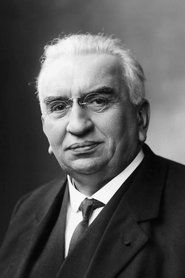

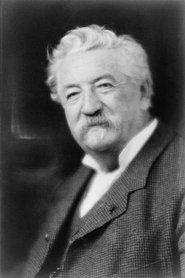

- Antoine Lumière, who appears in the film, was the father of the Lumière brothers and a successful photographer himself

- The Cinématographe camera used to film this weighed only about 5 kilograms, making it highly portable for outdoor shooting

- The film was shot on 35mm film with a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which became the standard for silent films

- Like many early Lumière films, this was likely shot in a single take without any editing or special effects

- The film was originally titled 'Départ en voiture' but is sometimes referred to in English as 'Leaving by Carriage'

- The servants loading luggage demonstrate the class structure of late 19th century French society

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to 'Départ en voiture' and other Lumière films was overwhelmingly positive, with audiences and critics alike marveling at the revolutionary technology that made moving images possible. Early reviews in French newspapers described the experience as magical and unprecedented, with many critics noting how the films made everyday scenes appear extraordinary simply through the act of filming them. Modern film historians and critics recognize this film as a seminal work that helped establish cinema's potential as both art and documentation. Scholars frequently cite it as an example of the Lumière brothers' observational style and their preference for capturing unmediated reality. The film is now regarded as a priceless historical artifact that provides an authentic window into late 19th-century life, with critics appreciating its simplicity and authenticity as virtues rather than limitations.

What Audiences Thought

The first audiences who viewed 'Départ en voiture' in December 1895 were reportedly astonished and delighted by the moving images. Contemporary accounts describe viewers gasping, applauding, and even recoiling in fear when the carriage appeared to move toward them (an early example of the 3D effect). The film's depiction of a familiar scene from daily life made it immediately accessible and relatable to audiences of the time. Unlike the fantastical stage productions popular at the time, this simple documentary of ordinary people preparing for a journey felt both magical and authentic to viewers. The film's brevity and simplicity worked in its favor, as audiences were still adjusting to the novelty of moving pictures. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film history courses typically approach it with historical appreciation, recognizing its importance as a foundational work of cinema while marveling at how much filmmaking technology has evolved in the intervening century.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Photography

- Stage magic

- Eadweard Muybridge's motion studies

- Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope

This Film Influenced

- Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895)

- Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895)

- The Sprinkler Sprinkled (1895)

- Baby's Lunch (1895)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and available through various film archives and institutions, including the Lumière Institute in Lyon, France. It has been digitally restored and is part of the collection of early cinema works maintained by film preservation organizations worldwide. The original nitrate film elements have been carefully preserved and transferred to modern safety film formats for long-term conservation.