Frankenstein

Plot

Frankenstein, a young medical student, becomes obsessed with creating the perfect human being through scientific experimentation. After months of intense study and chemical work, he successfully brings a creature to life, but it emerges as a grotesque, misshapen monster rather than the idealized being he envisioned. Horrified by his creation and physically weakened by the ordeal, Frankenstein returns home where his devoted fiancée Elizabeth nurses him back to health. On their wedding night, the monster appears, having developed a mirror-like ability to reflect Frankenstein's own evil back at him, causing the creature to gradually fade away. The experience transforms Frankenstein, who realizes that true beauty comes from within and that his scientific hubris has led him to create a reflection of his own inner darkness.

Director

About the Production

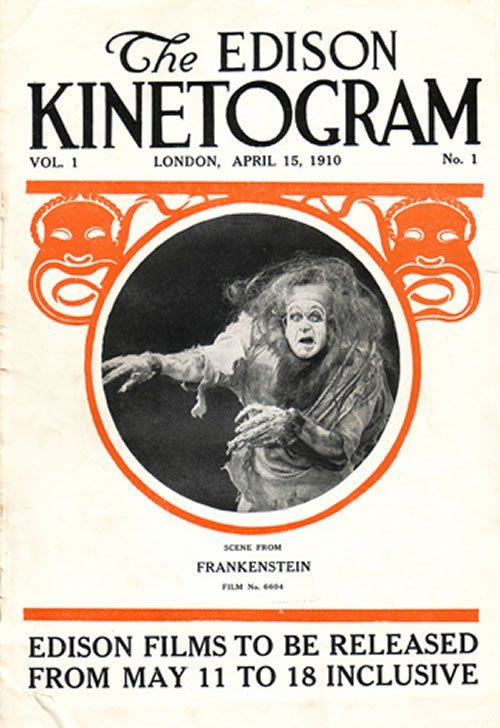

This was one of the earliest horror films ever made and the first film adaptation of Mary Shelley's novel. The production used innovative special effects for the time, including the creation sequence where the creature forms in a cauldron of chemicals. The monster's makeup was created by actor Charles Ogle himself, using a combination of cotton, putty, and various prosthetics to create the grotesque appearance. The film was shot in just three days, typical of the rapid production schedules of the era.

Historical Background

Made in 1910, this film emerged during a pivotal period in cinema history when movies were transitioning from short novelty acts to narrative storytelling. The Edison Manufacturing Company, though past its peak of dominance, was still producing hundreds of films annually. This was an era before film censorship codes, allowing for darker themes and more explicit horror elements. The film was created just three years after the first dramatic feature films appeared, and during a time when science was making rapid advances, creating public fascination and fear about the boundaries of human knowledge. The Progressive Era was in full swing, with debates about scientific ethics and the role of science in society becoming increasingly prominent. Mary Shelley's novel, published in 1818, was experiencing a resurgence of popularity, and its themes of scientific hubris resonated with contemporary anxieties about industrialization and technological progress.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a landmark in cinema history as the first horror film adaptation of a major literary work and one of the earliest examples of the science fiction horror genre. It established many visual and narrative conventions that would influence countless later Frankenstein adaptations, including the laboratory setting and the creation sequence. The film's portrayal of the monster as a reflection of its creator's inner darkness introduced a psychological dimension to horror storytelling that would become increasingly important in the genre. As an Edison production, it demonstrates how early American cinema was already tackling complex literary adaptations and sophisticated themes. The film's rediscovery in the 1970s provided film historians with crucial insights into early horror cinema techniques and storytelling methods. Its existence proves that horror as a film genre has roots stretching back to the very beginning of narrative cinema, challenging the assumption that horror was a later development.

Making Of

The film was directed by J. Searle Dawley, one of Edison's most reliable directors who had been making films since 1907. The production team faced significant challenges in creating the monster's appearance and the special effects for the creation sequence. Charles Ogle, an experienced character actor, took it upon himself to design his own makeup, creating a wild, unkempt look with heavy prosthetics that gave the creature a distinctly non-human appearance. The creation sequence was achieved through reverse photography and careful editing, showing the monster gradually forming in a cauldron of chemicals - a departure from the electrical reanimation in later adaptations. The Edison studio, known for its technical innovations, used double exposure techniques for the mirror sequence where the monster reflects Frankenstein's evil. The entire film was shot in just three days at Edison's Bronx studio, with interior sets built to represent Frankenstein's laboratory and home.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Edison productions of the era, employed static camera positions with careful staging to tell the story visually. The film used the innovative technique of reverse photography for the creation sequence, showing the monster forming from chemical elements. The lighting was dramatic for its time, using strong contrasts to create an ominous atmosphere in the laboratory scenes. The mirror sequence where the monster reflects Frankenstein's evil was achieved through careful editing and possibly double exposure techniques. The composition followed theatrical conventions, with actors positioned to maximize visibility and dramatic impact. The film's visual style established many horror conventions that would become standard in later decades, including the use of shadows and dramatic lighting to create suspense and fear.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations for its time, particularly in special effects. The creation sequence used reverse photography and careful editing to show the monster forming in a chemical cauldron, a complex effect for 1910. The makeup design by Charles Ogle was groundbreaking, using multiple layers of cotton, putty, and other materials to create a truly monstrous appearance that was unlike anything audiences had seen before. The film also experimented with psychological horror through its mirror sequence, suggesting the monster was a reflection of Frankenstein's inner evil - a sophisticated concept for early cinema. The production utilized Edison's improved film stock and cameras, resulting in relatively clear images for the period. The film's survival and restoration have also demonstrated advances in film preservation techniques, allowing modern audiences to experience this early horror classic in improved quality.

Music

As a silent film, 'Frankenstein' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate mood music, often improvising based on the action on screen. Edison studios sometimes provided suggested musical cues or scores for their films, though specific documentation for this film's original musical accompaniment is not available. Modern screenings and releases typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate classical music. The 2010 restoration by the Library of Congress included a new musical score composed specifically for the film, attempting to recreate the emotional impact that contemporary audiences would have experienced. The absence of synchronized dialogue meant that the visual storytelling and musical accompaniment had to carry the entire narrative and emotional weight of the production.

Famous Quotes

A liberal adaptation of Mrs. Shelley's famous story

Frankenstein: 'I have created a monster!'

Elizabeth: 'You must rest, my love'

Memorable Scenes

- The creation sequence where the monster forms in a cauldron of burning chemicals

- The monster's first appearance in Frankenstein's laboratory

- The wedding night confrontation where the monster reflects Frankenstein's evil

- The gradual fading of the monster as it reflects its creator's inner darkness

- Frankenstein's realization that the monster is a mirror of his own soul

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' and was made when the novel was still under copyright protection.

- The film was considered lost for decades until a print was discovered in the 1970s in the collection of a Wisconsin film collector.

- Unlike later adaptations, this version portrays the monster as a reflection of Frankenstein's own evil rather than a sympathetic character.

- The creation scene shows the monster forming in a cauldron of burning chemicals rather than through electricity as in later versions.

- Charles Ogle, who played the monster, also created his own makeup design, which was significantly different from the flat-topped look popularized by Boris Karloff.

- The film was produced by Thomas Edison's studio, which was one of the dominant film production companies of the early 1900s.

- At approximately 12 minutes, it's one of the shortest feature adaptations of Frankenstein ever made.

- The film was advertised as 'A Liberal Adaptation of Mrs. Shelley's Famous Story' to acknowledge the significant changes from the novel.

- The mirror effect where the monster reflects Frankenstein's evil was an original concept created for this film.

- This version introduces the character of Elizabeth as Frankenstein's fiancée, creating a romantic subplot not present in the novel's early chapters.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in 1910 were generally positive, with trade publications praising the film's ambitious scope and technical achievements. The Moving Picture World noted the film's 'thrilling' nature and commended the special effects, particularly the creation sequence. However, some critics felt the 12-minute runtime was insufficient to properly adapt Shelley's complex novel. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a historically significant work, with many appreciating its unique interpretation of the source material and its innovative visual effects for the period. Film historians have praised Charles Ogle's performance and makeup design as groundbreaking for the time. The film is now recognized as a crucial precursor to the Universal horror films of the 1930s and is studied for its early use of horror tropes and visual storytelling techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reactions in 1910 were mixed, with some viewers finding the monster's appearance genuinely frightening while others were amused by what now seems dated special effects. The film was popular enough to warrant wide distribution through Edison's exchange system, indicating commercial success. Contemporary audiences were particularly intrigued by the creation sequence, which was unlike anything they had seen before. When the film was rediscovered and screened in the 1970s, modern audiences were fascinated by its historical significance and its different approach to the Frankenstein mythos. Today, the film is primarily viewed by film students, historians, and classic cinema enthusiasts who appreciate its place in horror cinema history. The surviving print, available through various archives and online platforms, continues to attract viewers interested in the origins of horror cinema and early film adaptations of literary classics.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818 novel)

- The Golem (1915 film - later, but similar themes)

- German Expressionist cinema (later influence)

- Edison's previous horror experiments

This Film Influenced

- Frankenstein (1931)

- Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

- The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

- Young Frankenstein (1974)

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1994)

- Frankenstein (1994 TV film)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for approximately 60-70 years until a single 35mm print was discovered in the mid-1970s in the collection of Alois Dettlaff, a Wisconsin film collector. The print was in relatively good condition considering its age. In 2010, the Library of Congress completed a restoration of the film, preserving it for future generations. The restored version is now held by several film archives, including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. The film is in the public domain due to its age, which has contributed to its wider availability in recent years. The survival of this early horror classic is remarkable given that an estimated 90% of American silent films have been lost.