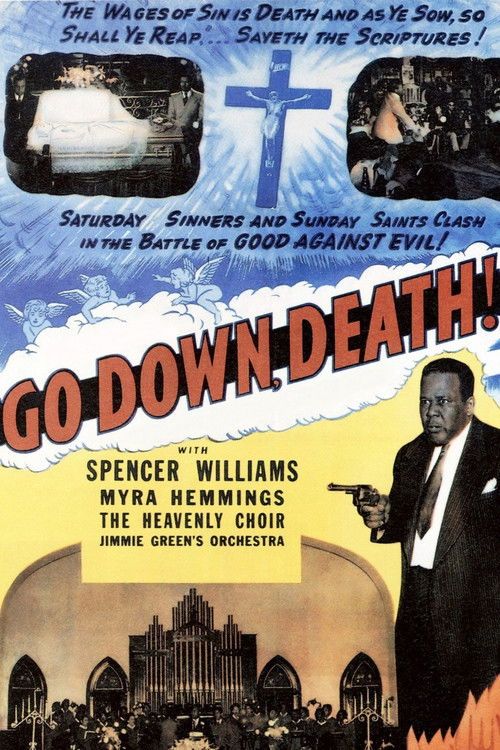

Go Down Death

"Saturday sinners and Sunday saints clash in a battle of good against evil!"

Plot

In a small African-American community, the corrupt criminal boss Big Jim Bottoms runs a successful juke joint that faces a sudden decline in business when a charismatic new preacher, Jasper Jones, arrives in town. To protect his profits, Big Jim orchestrates a devious plot to frame the innocent minister by staging and photographing him in scandalous, compromising positions with three local women. When Big Jim's devout adoptive mother, Aunt Caroline, discovers the scheme, she attempts to intervene and protect the preacher's reputation, leading to a violent confrontation where she is accidentally killed. Following her death, Big Jim manages to evade legal justice, but he is soon consumed by a terrifying, guilt-ridden psychological breakdown. The film culminates in a surreal sequence where Big Jim is haunted by visions of eternal damnation and the horrors of Hell, ultimately meeting a tragic end in a canyon as divine justice prevails.

About the Production

The film was produced by Alfred N. Sack, a prominent figure in the production of 'race films'—movies made specifically for Black audiences during the era of segregation. Director Spencer Williams, who also stars as the antagonist, was a pioneer of independent Black cinema and often worked with extremely limited resources. To compensate for the low budget and lack of special effects, Williams famously repurposed footage from the 1911 Italian silent epic 'L'Inferno' to depict the scenes of Hell. The production relied heavily on local non-professional actors and community members in Dallas to fill out the cast and choir.

Historical Background

Made in 1944 during the height of the Jim Crow era, 'Go Down Death' belongs to the 'race film' industry, which flourished between 1915 and the early 1950s. These films were produced for segregated Black audiences who were either excluded from or caricatured in mainstream Hollywood productions. During World War II, Black filmmakers like Spencer Williams provided essential cultural representation and moral guidance through cinema, often focusing on the tension between urban 'sin' (juke joints, gambling) and traditional Southern religious values. The film reflects the social reality of the 'Chitlin' Circuit,' where Black entertainers and films traveled through a network of safe venues in the segregated South and North.

Why This Film Matters

The film is a landmark of independent Black cinema, representing a period where African-American creators took control of their own narratives to counter the stereotypical 'minstrel' depictions common in Hollywood. It serves as an important document of mid-century Black religious life, music, and community values. By adapting the work of James Weldon Johnson, Williams bridged the gap between the Harlem Renaissance's literary achievements and the popular medium of film. Today, it is studied by film historians for its unique blend of folk religion, surrealism, and social commentary, as well as its status as a survivor of a largely lost era of filmmaking.

Making Of

Production of 'Go Down Death' was a masterclass in low-budget ingenuity. Spencer Williams often had to shoot in real locations around Dallas, such as local churches and homes, because he lacked the funds for studio sets. The use of 'L'Inferno' footage was not just an artistic choice but a necessary shortcut to provide a visual spectacle that the production could never have afforded to film from scratch. Williams worked closely with the Black community in Dallas, often casting real ministers and choir members to lend the film a sense of spiritual authenticity. The filming process was rapid, often completed in just a few weeks, to keep costs at a minimum for Sack Amusement Enterprises.

Visual Style

The film was shot in black-and-white by cinematographer H.W. Kier. Due to budget constraints, the visual style is largely functional, utilizing static shots and natural lighting. However, the film becomes visually experimental during the supernatural sequences, using double exposures to depict ghosts and the jarring insertion of high-contrast, grainy footage from 'L'Inferno' to create a nightmarish, collage-like aesthetic for the afterlife scenes.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement is its early use of 'found footage' or 'stock footage' as a narrative device. By integrating 30-year-old silent film clips into a contemporary sound film, Williams created a proto-postmodern aesthetic. Additionally, the film's use of double exposure to represent the spirit of Aunt Caroline's late husband was a sophisticated effect for such a low-budget independent production.

Music

The soundtrack is a rich tapestry of 'Negro spirituals' and traditional gospel music, which often takes precedence over the dialogue. It features performances by The Heavenly Choir and Jimmie Green's Orchestra. The music serves as the emotional heartbeat of the film, reinforcing the religious themes and providing a sense of cultural familiarity for the 1940s audience.

Famous Quotes

Jasper Jones: 'Purity of heart was the very essence of Christ's message.'

Aunt Caroline: 'Jim, I'm not going to give you these pictures. I'll die first!'

Big Jim Bottoms: 'I'm going to show you the kind of bait to use in your preacher trap.'

Narrator (reciting Johnson): 'And Death began to ride again—up beyond the morning star, into the glittering light of glory...'

Memorable Scenes

- The 'Hell' Sequence: A surreal montage where Big Jim is haunted by demons and fire, utilizing repurposed footage from the 1911 silent film 'L'Inferno'.

- Aunt Caroline's Death: A tense struggle in Big Jim's office where the moral heart of the film is silenced, leading to the protagonist's ultimate downfall.

- The Funeral Sermon: A lengthy, powerful sequence where the preacher recites James Weldon Johnson's poem as the camera cuts to symbolic imagery of the soul's journey to heaven.

- The Ghostly Visitation: Aunt Caroline's late husband appears as a transparent spirit to help her find the incriminating photographs in Big Jim's safe.

Did You Know?

- The film's title and central theme are derived from the famous poem 'Go Down Death' by African-American writer James Weldon Johnson, found in his 1927 collection 'God's Trombones'.

- Director Spencer Williams later became nationally famous for playing the character Andrew 'Andy' Hogg Brown in the television version of 'Amos 'n' Andy'.

- To create the elaborate 'Hell' sequences, Williams used clips from the 1911 Italian silent film 'L'Inferno', which was the first full-length Italian feature film.

- The film ran into significant censorship issues in Maryland, New York, and Ohio due to the 'Hell' sequences, which contained brief nudity from the original 1911 footage.

- Myra D. Hemmings, who plays Aunt Caroline, was a prominent educator and one of the original founders of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

- This was the third film in a religious-themed trilogy directed by Williams, following 'The Blood of Jesus' (1941) and the now-lost 'Brother Martin: Servant of Jesus' (1942).

- The film features authentic gospel music performed by The Heavenly Choir and Jimmie Green's Orchestra.

- Despite being a 'race film' intended for Black audiences, the production was financed and distributed by Alfred Sack, a white businessman based in Dallas.

- The 'Hell' sequence in Ohio was specifically ordered to be edited to remove a scene of a devil chewing on a man's head.

- The film is often cited as a prime example of the 'morality play' genre within early Black independent cinema.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, 'Go Down Death' was highly successful within its intended market, praised by Black newspapers and audiences for its moral message and musical performances. However, mainstream white critics of the 1940s largely ignored it. Modern critics view the film with a mix of historical reverence and technical critique; while some find the acting 'stiff' and the production values 'primitive,' others like Jonathan Rosenbaum have praised Williams' 'visionary' and 'idiosyncratic' directorial style. It is now recognized as a vital piece of American film history, though it is often considered less technically polished than Williams' debut, 'The Blood of Jesus'.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Black audiences embraced the film as a powerful 'morality tale' that resonated with their spiritual beliefs. The inclusion of popular gospel music and the familiar conflict between the church and the 'juke joint' made it a staple in community screenings. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history, often find the 'Hell' sequences and the surreal ending to be the most memorable and striking aspects of the viewing experience.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- James Weldon Johnson's 'God's Trombones' (Poetry)

- L'Inferno (1911 film)

- Traditional African-American oral preaching traditions

- Dante's Inferno

This Film Influenced

- Daughters of the Dust (1991)

- Eve's Bayou (1997)

- The films of the L.A. Rebellion movement

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is in the public domain and has been preserved by various archives, including the Library of Congress. It was notably restored and included in the 'Pioneers of African-American Cinema' collection by Kino Lorber.