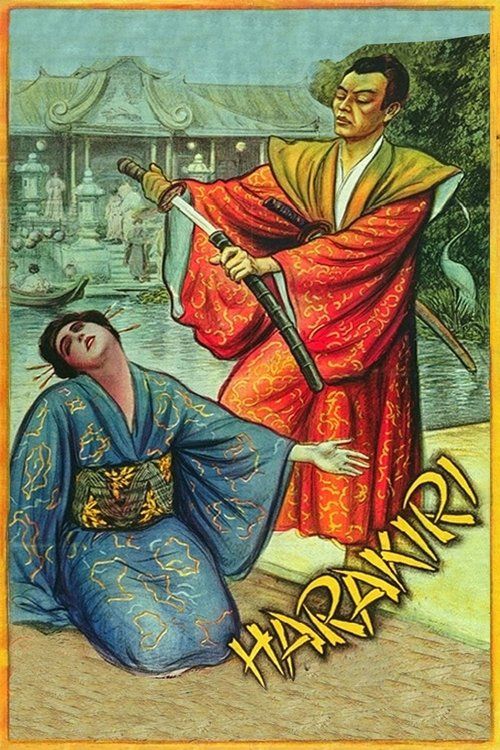

Harakiri

"A Tale of Love, Honor, and Betrayal from the Land of the Rising Sun"

Plot

In feudal Japan, a young woman named O-Taki is the daughter of a disgraced daimyo who forces her to commit harakiri to secure her family's honor and her own future. However, instead of dying, she survives the ritual and flees to a coastal town where she meets and falls deeply in love with a European naval officer. They marry and have a child together, but when the officer must return to Europe, he promises to come back for them. Years later, he returns to Japan, but to O-Taki's devastating shock, he brings his European wife with him, having abandoned his Japanese family. The film culminates in a tragic confrontation where O-Taki, now truly understanding the meaning of sacrifice and betrayal, must decide her ultimate fate.

About the Production

This was one of Fritz Lang's earliest directorial efforts, made during his formative period at Decla-Bioscop. The film was notable for its elaborate Japanese sets constructed in Berlin studios, which were considered quite authentic for the time. Lang's attention to detail in recreating Japanese culture and customs was remarkable for a 1919 European production. The harakiri sequence was particularly controversial for its graphic depiction, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in cinema at the time.

Historical Background

1919 was a pivotal year in German history, marking the end of World War I and the beginning of the Weimar Republic. The country was experiencing political upheaval, economic hardship, and cultural renaissance. German cinema was undergoing a transformation, moving away from the more straightforward narratives of the war years toward more expressionistic and psychologically complex films. 'Harakiri' emerged during this period of artistic experimentation, reflecting both the fascination with exotic cultures that characterized European modernism and the exploration of trauma and betrayal that resonated with post-war German audiences. The film's themes of honor, sacrifice, and cultural collision spoke to a nation grappling with its own identity and place in the world after a devastating defeat.

Why This Film Matters

While not as well-known as Lang's later masterpieces, 'Harakiri' represents an important early work in the director's filmography and in the development of German expressionist cinema. The film demonstrates Lang's early interest in themes of cultural conflict, moral ambiguity, and the destructive nature of rigid social codes - themes that would permeate his entire career. Its visual style, with its dramatic use of shadow and carefully composed frames, hints at the expressionistic techniques that would come to define German cinema in the 1920s. The film also reflects the Western fascination with Japanese culture that was prevalent in the early 20th century, though viewed through a distinctly European lens. Its exploration of cross-cultural relationships and the tragic consequences of misunderstanding and betrayal remains relevant today.

Making Of

The production of 'Harakiri' took place during a turbulent period in German history, immediately following World War I. Fritz Lang, who had served in the war and was injured, was just beginning his directorial career. The film was shot at Decla-Bioscop's studios in Berlin, where elaborate sets were constructed to recreate feudal Japan. Lang was known for his meticulous attention to detail and demanded authenticity in the costumes and props. The harakiri sequence required careful choreography and special effects to achieve its shocking realism. The cast, particularly Lil Dagover, underwent extensive preparation to understand Japanese customs and mannerisms. The film's cinematographer was Carl Hoffmann, who would later work with Lang on many of his most famous films including 'Metropolis'. The production faced challenges due to post-war shortages, but the studio invested heavily in the film's exotic setting to capitalize on European fascination with Asian culture.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Carl Hoffmann employed innovative techniques for its time, including dramatic use of shadows and carefully composed frames that hinted at the expressionistic style to come. The film made effective use of chiaroscuro lighting to create emotional intensity, particularly in the harakiri sequence. The Japanese sets were photographed to emphasize their exotic beauty while maintaining a sense of authenticity. Hoffmann utilized close-ups to capture the emotional turmoil of the characters, particularly Lil Dagover's expressive performance. The film also featured some tracking shots and camera movements that were relatively sophisticated for 1919, demonstrating Lang's early interest in dynamic visual storytelling.

Innovations

For 1919, 'Harakiri' featured several notable technical achievements. The film's production design included some of the most elaborate Japanese sets constructed in Germany up to that time. The special effects used in the harakiri sequence were particularly advanced for the period, creating a convincing illusion of self-harm without actual injury. The film also experimented with color tinting, with different scenes tinted in appropriate colors to enhance mood and atmosphere - blue for night scenes, amber for interiors, and red for the dramatic climax. The cinematography employed innovative camera movements and angles that were ahead of their time, helping establish the visual language that would define German expressionist cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Harakiri' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces and original compositions performed by a theater organist or small orchestra. The music would have been synchronized with the film's emotional beats, with dramatic themes for the harakiri sequence, romantic motifs for the love scenes, and Japanese-inspired melodies to establish the cultural setting. No original score recordings exist from 1919, but modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to capture the film's blend of Japanese and Western sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

Honor is heavier than a mountain, but death is lighter than a feather

In choosing my own death, I found my own life

Your promises were written on water

The West takes what it wants, the East gives what it must

Memorable Scenes

- The harakiri sequence where O-Taki undergoes the ritual suicide attempt, filmed with shocking realism for 1919

- The first meeting between O-Taki and the European officer on the Japanese coast

- The devastating confrontation scene when the officer returns with his European wife

- The final scene where O-Taki must choose her ultimate destiny

Did You Know?

- This was Fritz Lang's third film as a director, following 'Der Herr der Liebe' and 'Die Spinnen'.

- The film was also known by the alternate title 'The Mad Monk' in some international markets.

- Lil Dagover, who played O-Taki, would later become one of Germany's most famous silent film stars, notably starring in 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari'.

- The film was part of a wave of 'exotic' European productions in the late 1910s that explored non-Western cultures.

- Despite being set in Japan, no Japanese actors were used in the production, which was typical for European films of this period.

- The harakiri scene was so realistic that it caused controversy upon release, with some critics calling it too graphic for cinema.

- The film's themes of cultural clash and betrayal would become recurring motifs in Lang's later work.

- Original prints of the film were tinted in different colors to enhance the emotional impact of various scenes.

- The production design was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints that were popular in Europe at the time.

- This film is sometimes confused with Masaki Kobayashi's 1962 film of the same name, though they are completely unrelated.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1919 praised the film's visual beauty and Lil Dagover's performance, though some found the subject matter shocking. German film journals of the period noted the film's technical sophistication and Lang's promising directorial hand. The harakiri sequence generated particular discussion, with some reviewers calling it unnecessarily graphic while others praised its emotional power. In retrospect, film historians view 'Harakiri' as an important stepping stone in Lang's development as a filmmaker, showing early signs of the visual and thematic concerns that would define his later masterpieces. Modern critics have noted the film's role in establishing Lang's recurring interest in themes of fate, justice, and cultural collision.

What Audiences Thought

The film found moderate success with German audiences in 1919, who were drawn to its exotic setting and dramatic storyline. The combination of romance, tragedy, and cultural exoticism appealed to post-war cinema-goers seeking escape and emotional engagement. Lil Dagover's performance was particularly well-received, helping establish her as a rising star in German cinema. The shocking nature of the harakiri scene generated word-of-mouth publicity, though it also made the film controversial in some circles. While it didn't achieve the blockbuster status of some other releases from the same period, it maintained enough popularity to justify international distribution, where it found audiences interested in stories about Japan.

Awards & Recognition

- No awards were given for this film in 1919, as the major film awards had not yet been established

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Japanese woodblock prints

- German expressionism (emerging)

- Contemporary literature about Japan

- Theater traditions of melodrama

This Film Influenced

- Lang's later films dealing with similar themes of fate and justice

- Other German exotic films of the 1920s

- Cross-cultural romance films in European cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments and incomplete copies surviving in various film archives. Some sequences exist only in poor condition, though restoration efforts have been undertaken by film preservation institutions. The most complete version is held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin, though it remains incomplete. The film's status reflects the unfortunate fate of many silent-era films, with an estimated 75-90% of silent films considered lost.