Japanese War Bride

"The story of a love that dared to defy a town's hatred!"

Plot

Korean War veteran Jim Sterling returns to his small farming community in California with his new Japanese wife, Tae Shimizu, whom he met while stationed in Japan. The couple faces intense prejudice from Jim's family and neighbors, who cannot accept their interracial marriage. Jim's mother and sister are particularly hostile, while his former girlfriend, Fran, attempts to sabotage their relationship. Despite the mounting pressure, including economic boycotts and social ostracism, Jim and Tae's love endures as they struggle to build a life together in a community unwilling to accept them. The film culminates in a crisis that forces the townspeople to confront their own bigotry and the couple to fight for their right to live in peace.

About the Production

The film was controversial upon release due to its interracial marriage theme during the Korean War period. Director King Vidor fought with the Production Code Administration to get the film approved, as interracial marriage was still illegal in many states. The Japanese character was originally offered to several Japanese actresses before Shirley Yamaguchi was cast. Production faced challenges finding locations willing to host filming due to the sensitive subject matter.

Historical Background

Released during the Korean War (1950-1953), the film emerged at a time when anti-Japanese sentiment from World War II still lingered in American society. The early 1950s saw the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, and this film was one of the first mainstream Hollywood productions to address racial prejudice directly. The period also marked the end of the U.S. occupation of Japan (1945-1952), and American soldiers returning with Japanese wives became a growing social phenomenon. The film's release coincided with the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act of 1952, which maintained strict quotas on Asian immigration while allowing for some exceptions, including for military spouses. California, where the film is set, still had anti-miscegenation laws that would not be struck down until 1948's Perez v. Sharp decision, though enforcement varied.

Why This Film Matters

Japanese War Bride stands as a pioneering film in Hollywood's treatment of interracial relationships and Asian representation. While not entirely free from stereotypes, it was one of the first major American films to portray a Japanese character with dignity and depth, and to present an interracial marriage in a sympathetic light. The film helped pave the way for later films dealing with similar themes, such as 'Sayonara' (1957) and 'The World of Suzie Wong' (1960). It also reflected and influenced changing American attitudes toward race and marriage in the postwar period. The film's existence demonstrated that even during the repressive McCarthy era, socially conscious cinema could find its way to audiences. It remains an important historical document of Hollywood's gradual evolution toward more inclusive storytelling.

Making Of

King Vidor, a veteran director known for his social consciousness, personally financed much of the film through his own production company after major studios passed on the project. The casting of Shirley Yamaguchi (also known as Yoshiko Yamaguchi and Li Xianglan) was particularly significant, as she was a major star in Asia but relatively unknown in America. The film faced numerous censorship challenges from the Production Code Administration, which initially objected to the positive portrayal of interracial marriage. Vidor had to make several compromises, including emphasizing the 'exotic' aspects of Japanese culture, to get approval. The rural California town was recreated on a studio backlot due to difficulties finding actual locations willing to participate. Many Japanese-American actors were cast in supporting roles, a rarity for Hollywood films of this era.

Visual Style

Shot by cinematographer Russell Harlan, the film employs a naturalistic style that contrasts the warm, intimate moments between the couple with the harsh, judgmental gazes of the townspeople. Harlan uses soft focus techniques during romantic scenes to emphasize the couple's isolation from the hostile world around them. The rural California setting is captured with sweeping landscape shots that emphasize both the beauty of the American countryside and the isolation of the couple within it. The film's visual language subtly reinforces its themes, often framing Tae as an outsider through doorways and windows, visually representing her position as an 'other' in the community.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking technically, the film employed innovative sound recording techniques to capture dialogue in outdoor scenes with natural ambient noise, enhancing the realism of the rural setting. The makeup department developed new techniques for Shirley Yamaguchi's appearance to ensure she looked authentically Japanese without resorting to caricature. The film's editing style, particularly in sequences showing the passage of time and the gradual hardening of community attitudes, was considered sophisticated for a modest production. The production design team created a convincing small-town atmosphere on a limited budget through careful use of existing locations and minimal set construction.

Music

The musical score was composed by Louis Gruenberg, who incorporated subtle Japanese musical elements into traditional Hollywood orchestration to represent Tae's cultural background. The soundtrack uses leitmotifs to distinguish between the American and Japanese characters, with Tae's themes featuring pentatonic scales and traditional Japanese instrumentation. The score avoids overt exoticism while still signaling cultural differences through musical means. The film's title song, 'Japanese War Bride,' was performed by a popular vocalist of the era but did not become a hit. The overall musical approach emphasizes the emotional journey of the characters rather than making a political statement.

Famous Quotes

Love doesn't know what color skin it wears.

In America, we're all supposed to be equal... but some of us are more equal than others.

You can't choose who you love, but you can choose how you love them.

Prejudice is a disease that spreads faster than any plague.

Home isn't a place, it's where people accept you for who you are.

Memorable Scenes

- The tense dinner scene where Tae tries to cook an American meal for Jim's family, who silently judge her every move

- The emotional confrontation between Jim and his mother when she refuses to accept his marriage

- The community meeting where townspeople vote to boycott Jim's farm due to his marriage

- The tender scene where Jim teaches Tae how to dance to American music in their small kitchen

- The climactic scene where Jim stands up to the entire town, defending his wife and their right to live in peace

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the first Hollywood productions to directly address interracial marriage between Americans and Japanese after World War II

- Director King Vidor was blacklisted during the McCarthy era but continued to work through independent production

- The film's release coincided with the end of Allied occupation of Japan, making its themes particularly timely

- Shirley Yamaguchi, who played Tae, was actually Chinese-born and had previously been imprisoned in China for alleged collaboration with the Japanese

- The film was banned in several Southern states due to its depiction of interracial marriage

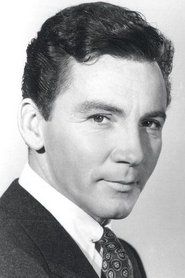

- Don Taylor, who played Jim Sterling, had actually served in the Army Air Forces during World War II

- The original title was 'The Japanese Bride' but was changed to 'Japanese War Bride' for marketing purposes

- United Artists initially hesitated to distribute the film due to its controversial nature

- The film's modest budget forced Vidor to use many unknown actors in supporting roles

- Real Japanese-American community leaders were consulted during production to ensure authentic representation

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but generally positive about the film's intentions. The New York Times praised its 'courageous treatment of a difficult subject' while noting that 'the execution sometimes falls short of the noble intentions.' Variety called it 'a well-meaning if somewhat preachy social problem film.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, recognizing its historical importance despite some dated elements. Film historians often cite it as an early example of Hollywood's attempt to address racial prejudice, though they note its limitations in truly challenging the racial hierarchies of its time. The film's reputation has grown in recent years as scholars have rediscovered Vidor's work and his commitment to social issues.

What Audiences Thought

The film performed modestly at the box office, finding its strongest reception in urban areas and among more liberal audiences. Rural audiences, particularly in the South and Midwest, were often unreceptive, with some theaters refusing to book the film. Japanese-American community response was cautiously optimistic, appreciating the attempt at sympathetic portrayal while noting some cultural inaccuracies. Veterans' groups had mixed reactions, with some praising the film's recognition of soldiers' experiences and others uncomfortable with its racial themes. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among classic film enthusiasts and scholars interested in Hollywood's treatment of race and ethnicity.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Gentleman's Agreement (1947)

- Pinky (1949)

- Home of the Brave (1949)

- No Way Out (1950)

- The Men (1950)

This Film Influenced

- Sayonara (1957)

- The World of Suzie Wong (1960)

- A Majority of One (1961)

- My Geisha (1962)

- The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in its complete form and has been preserved by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. A 35mm nitrate original negative is stored at the Library of Congress. The film entered the public domain in the United States in 1980 due to copyright renewal failure, which has led to numerous poor quality DVD releases. A restored version was screened at the TCM Classic Film Festival in 2015 as part of a retrospective on King Vidor's work. The film is occasionally broadcast on Turner Classic Movies in restored form.