Kunku

"A bold statement against social injustice and the exploitation of women"

Plot

Neera, a young and educated woman, is forced into a marriage with Kakasaheb, an elderly progressive lawyer who is a widower with two children nearly Neera's age. Despite Kakasaheb's modern views on social reform, Neera refuses to consummate the marriage, declaring that while suffering can be endured, injustice cannot be accepted. She faces constant opposition from her manipulative mother-in-law who wants grandchildren, and her lecherous stepson Pandit who makes inappropriate advances toward her. Neera finds an ally in Kakasaheb's daughter Sushila, who understands her plight, and eventually Kakasaheb himself comes to respect Neera's principles. The film culminates with Kakasaheb acknowledging the injustice of the marriage and agreeing to grant Neera her freedom, making a powerful statement about women's autonomy and the need to reform oppressive social customs.

Director

About the Production

Directed by V. Shantaram during his most creative period at Prabhat Studios. The film was shot simultaneously in Marathi as 'Kunku' and Hindi as 'Duniya Na Mane'. Shantaram was known for his progressive social themes and this film was considered one of his most daring works, tackling the sensitive subject of child marriage and women's rights in conservative 1930s India.

Historical Background

Made in 1937, during the peak of the Indian independence movement, 'Kunku' emerged at a time when India was experiencing significant social reform movements. The 1930s saw intense debates about women's rights, child marriage, and social customs, with reformers like Mahatma Gandhi and B.R. Ambedkar advocating for change. The film reflected the growing consciousness about women's issues in Indian society and the cinema of the time. It was produced just a decade after the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, which made child marriage illegal, though the practice continued in many parts of India. The film's release coincided with increased political awareness and the rise of progressive movements across the country, making it particularly relevant to contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'Kunku' is considered a landmark film in Indian cinema history for its bold feminist stance and social commentary. It was one of the first Indian films to explicitly challenge patriarchal traditions and advocate for women's autonomy. The film's impact extended beyond cinema, influencing public discourse on marriage reform and women's rights. It established V. Shantaram as a director committed to social change and created a template for socially relevant cinema in India. The film's success proved that audiences were ready for progressive content, paving the way for more reformist films in Indian cinema. Its influence can be seen in later films dealing with women's issues, and it remains a reference point for feminist cinema in India. The film is now studied in film schools as an example of early Indian parallel cinema and its role in social reform.

Making Of

V. Shantaram was deeply committed to social reform themes throughout his career, and 'Kunku' represented his boldest statement yet on women's rights. The production faced significant challenges from conservative elements who objected to the film's critique of traditional marriage customs. Shanta Apte, who played Neera, was not just an actress but also a trained classical singer, and she brought a unique intensity to the role. The film's realistic approach was revolutionary for its time, with Shantaram insisting on natural performances rather than the theatrical style common in Indian cinema of the 1930s. The production team conducted extensive research into actual cases of forced marriages to ensure authenticity. The film's controversial nature meant that the cast and crew faced social backlash, but they remained committed to the project's message.

Visual Style

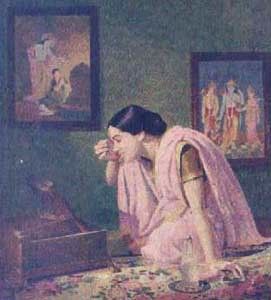

The cinematography by K. D. Kaushik was innovative for its time, using lighting and camera angles to emphasize Neera's isolation and oppression. The film employed close-ups effectively to convey the characters' emotions, particularly Neera's defiance and suffering. The prison-like quality of the traditional household was emphasized through low-angle shots and shadows. The camera work was more naturalistic than the theatrical style common in 1930s Indian cinema, reflecting V. Shantaram's influence from international cinema. The film's visual language was sophisticated for its era, with symbolic use of objects like locked doors and barred windows to represent Neera's confinement.

Innovations

'Kunku' was technically advanced for its time, featuring innovative use of sound recording to capture natural dialogue rather than the exaggerated delivery common in early Indian talkies. The film employed sophisticated editing techniques to build tension and emotional impact. V. Shantaram experimented with narrative structure, using flashbacks and symbolic sequences that were uncommon in Indian cinema of the 1930s. The film's production design authentically recreated a middle-class Maharashtrian household of the era. The dual-language production was technically challenging, requiring careful coordination to maintain consistency across both versions.

Music

The music was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, with lyrics by Shantaram Athavale. The soundtrack included several songs that became popular, particularly those sung by Shanta Apte herself, who was a trained classical singer. The songs were not mere entertainment but served to advance the narrative and express Neera's inner turmoil. The film's use of music was restrained compared to typical Indian films of the era, reflecting its serious social theme. One particular song expressing Neera's resolve became an anthem for women's rights activists of the time. The background score was minimal but effective, using traditional Indian instruments to enhance emotional moments.

Famous Quotes

"Dukh sahya jaate, par anyay nahi" (Suffering can be endured, but injustice cannot be accepted)

"Main ek insaan hoon, ek vastu nahi jo kisi ki marzi se chal sakti ho" (I am a human being, not an object that can be moved by someone's will)

"Shadi ek bandhan nahi, samjhdari ka sawal hai" (Marriage is not a bondage, but a question of understanding)

"Jab tak aurat apni awaz nahi dhadegi, tab tak samaj nahi badhega" (Until a woman raises her voice, society will not progress)

Memorable Scenes

- Neera's powerful monologue refusing to consummate the marriage, declaring her stance against injustice

- The confrontation scene between Neera and her lecherous stepson Pandit, where she firmly rejects his advances

- The emotional climax where Kakasaheb acknowledges Neera's suffering and grants her freedom

- The symbolic scene where Neera stands before locked doors representing her confinement

- The tense family dinner scene where tensions between Neera and her in-laws come to a head

Did You Know?

- The film was made in two versions simultaneously - Marathi as 'Kunku' and Hindi as 'Duniya Na Mane' - a common practice in early Indian cinema

- Shanta Apte's performance was so powerful that she became known as one of Indian cinema's first feminist icons

- The film was banned in several princely states due to its controversial subject matter challenging traditional marriage customs

- Director V. Shantaram was inspired to make this film after witnessing real-life cases of young women forced into marriages with older men

- The film's title 'Kunku' refers to the turmeric powder applied in Hindu marriage ceremonies, symbolizing the very institution the film critiques

- It was one of the first Indian films to explicitly address the issue of a woman's right to refuse physical relations in a marriage

- The film was screened at several international film festivals, including Venice, bringing attention to Indian social cinema

- Shanta Apte reportedly fasted for several days to achieve the gaunt, determined look of Neera in the film's later portions

- The stepson character was controversial for its time, as it hinted at incestuous desires, a taboo subject in 1930s Indian cinema

- The film's success led to V. Shantaram being considered one of India's most socially conscious directors

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Kunku' for its courage in tackling a sensitive social issue and its artistic excellence. The Times of India called it 'a bold step forward for Indian cinema' and particularly lauded Shanta Apte's performance as 'revelatory'. Filmindia magazine, one of the most influential film publications of the time, gave it an enthusiastic review, calling it 'the most important social film of the year'. International critics who saw the film at various festivals were impressed by its universal message and sophisticated storytelling. Modern critics and film historians consider it a masterpiece of early Indian cinema, with many ranking it among the top Indian films ever made. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of Indian cinema and women's representation in media.

What Audiences Thought

The film was received with enthusiasm by progressive audiences and young people, particularly in urban areas where social reform movements had gained traction. Many women viewers reportedly found the film empowering and relatable. However, it faced opposition from conservative sections of society, with some theaters facing protests from traditionalist groups. Despite the controversy, the film was a commercial success, running for several weeks in major cities. The dual-language strategy (Marathi and Hindi versions) helped it reach a wider audience across different regions. Word-of-mouth publicity was strong, with many viewers recommending it for its important social message. The film's success proved that Indian audiences were ready for serious, socially relevant content alongside entertainment.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film at the Bombay Film Society Awards (1937)

- Best Actress Award for Shanta Apte at the Indian Motion Picture Congress (1939)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European realist cinema of the 1930s

- Indian social reform movements

- Victorian literature dealing with women's issues

- Russian cinema's social themes

- Gandhian philosophy of social change

This Film Influenced

- Ardhangini (1940)

- Dahej (1950)

- Bandini (1963)

- Mirch Masala (1987)

- Lekin... (1990)

- Matrubhoomi: A Nation Without Women (2003)

- Parched (2015)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) and is considered part of India's cinematic heritage. Both the Marathi and Hindi versions have been restored, though some prints show signs of deterioration common with films of this era. The restored versions have been screened at various film festivals and retrospectives. The film is also preserved in international archives including the British Film Institute. Digital restoration work has been undertaken to ensure the film's survival for future generations.