Le Fils de Locuste

Plot

In ancient Rome, Locusta, the infamous poisoner who serves Emperor Nero, prepares a deadly potion intended for one of the emperor's enemies. However, in a tragic twist of fate, her own son discovers the poisoned drink and, unaware of its deadly nature, consumes it. The film follows Locusta's horror and despair as she witnesses the consequences of her deadly profession affecting her own family. The narrative explores themes of maternal guilt, the corrupting influence of power, and the inescapable consequences of one's actions in Nero's decadent court. As the story unfolds, viewers witness the tragic irony of the poisoner's child becoming a victim of her own deadly craft.

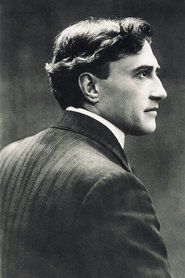

Director

About the Production

This film was part of Louis Feuillade's series of historical dramas and moral tales produced for Gaumont. The production utilized the limited but effective studio sets typical of early French cinema, with careful attention to period costumes and props to evoke ancient Rome. The film was shot in black and white on 35mm film, using the natural lighting techniques common in the pre-artificial lighting era of filmmaking.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1911, during what many film historians consider the golden age of French cinema before World War I. This period saw French cinema, particularly Gaumont and Pathé, dominating the global film market. The year 1911 was significant in film history as it marked the transition from short films to longer narratives, though this film maintained the shorter format typical of the period. The film's historical subject matter reflected the contemporary fascination with ancient Rome that was common in European arts and literature. France in 1911 was experiencing the Belle Époque, a period of cultural and artistic flowering, though tensions were building that would eventually lead to World War I. The film industry was rapidly evolving, with new techniques and storytelling methods being developed, and directors like Feuillade were at the forefront of these innovations.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early French narrative cinema and Louis Feuillade's contribution to the development of film language. As part of the historical drama genre, it demonstrates how early filmmakers used historical settings to explore contemporary moral and social themes. The film's focus on maternal guilt and the consequences of criminal behavior reflects the moralistic tone that characterized much of early cinema, which often served as both entertainment and moral instruction. The film also illustrates the sophisticated narrative techniques that French directors were developing in the early 1910s, including more complex character motivations and emotional depth than was typical of earlier cinema. Its existence today provides valuable insight into the artistic and cultural values of pre-WWI French society and the state of cinematic art during this crucial developmental period.

Making Of

Louis Feuillade directed this film during his tenure as artistic director at Gaumont, where he was responsible for overseeing the company's entire film production while also directing his own projects. The casting of Yvette Andréyor marked the beginning of a significant professional relationship that would span many years and include some of Feuillade's most celebrated works. The film was produced using the studio system that Gaumont had developed, with actors working on multiple films simultaneously and production schedules that were remarkably efficient by modern standards. The historical setting required careful attention to costume design and props, with the studio maintaining a collection of period pieces for their historical productions. The filming techniques employed were typical of the era, with static camera positions and theatrical-style acting that was considered appropriate for the medium at the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Le Fils de Locuste' reflects the techniques common in French cinema of 1911. The film was likely shot using stationary camera positions, with careful composition of scenes within the frame to guide the audience's attention. The use of natural light from studio skylights would have created dramatic shadows and highlights that enhanced the emotional tone of the story. The film may have employed hand-tinting techniques to add color to certain scenes, a practice Gaumont was experimenting with during this period. The visual style would have emphasized clarity and legibility, ensuring that the narrative could be understood without dialogue. The cinematographer would have worked closely with Feuillade to create visual compositions that supported the dramatic arc and emotional beats of the story.

Innovations

While 'Le Fils de Locuste' does not represent a major technical breakthrough in cinema history, it demonstrates the sophisticated filmmaking techniques that French directors had developed by 1911. The film showcases effective use of cross-cutting and narrative pacing within its short duration. The production likely utilized Gaumont's advanced studio facilities and equipment, which were among the best in Europe at the time. The film's preservation of dramatic tension and emotional clarity within the constraints of silent cinema demonstrates the advanced understanding of film language that Feuillade and his team had achieved. The effective use of costume and set design to create historical atmosphere within the limited resources of early cinema also represents a notable technical achievement for the period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Le Fils de Locuste' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have consisted of a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate music to match the mood of each scene. The score would likely have drawn from classical repertoire and popular music of the era, with selections chosen to enhance the emotional impact of key moments. For a dramatic film with themes of tragedy and maternal love, the music would have included somber, emotional pieces that reinforced the narrative's moral and emotional content. No original composed score exists for the film, as was common for productions of this era.

Did You Know?

- Louis Feuillade was one of the most prolific directors of the silent era, directing over 600 films in his career

- The film's title character Locusta was based on a real historical figure who was executed by Nero's successor Galba

- This film was released during the peak of Feuillade's creative period at Gaumont, before he created his famous serials like 'Fantômas'

- The film was likely tinted by hand for color effects, a common practice in early French cinema

- Yvette Andréyor would later become one of Feuillade's most frequent collaborators, starring in his major serials

- The film represents an early example of the historical drama genre that would become popular in European cinema

- At only 12 minutes, the film was typical of the short format that dominated cinema before feature-length films became standard

- The story reflects the moralistic tone common in early French cinema, often exploring themes of crime and punishment

- This film was part of Gaumont's strategy to compete with Pathé's historical epics

- The film's preservation status reflects the fragility of early nitrate film stock

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to trace due to the limited documentation of film reviews from this early period. However, films by Louis Feuillade were generally well-regarded by French critics of the time, who appreciated his narrative sophistication and technical skill. The film likely received positive attention in trade publications like Ciné-Journal and Pathé's own promotional materials. Modern film historians and scholars view this film as an important example of Feuillade's early work and his contribution to the development of narrative cinema. The film is often cited in studies of early French cinema and Feuillade's filmography, though it is less well-known than his later serial works. Contemporary critics who have been able to view surviving prints note the film's efficient storytelling and effective use of the short format.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1911 would have been influenced by the growing popularity of cinema as a form of entertainment among urban French populations. The film's historical subject matter and dramatic storyline would have appealed to audiences seeking both entertainment and moral lessons. The short format made it suitable for the typical cinema program of the era, which usually consisted of multiple short films. While specific audience reactions are not documented, the continued production of similar films by Gaumont suggests that audiences responded positively to this type of content. The film's themes of maternal love and tragic irony would have resonated with contemporary audiences who valued emotional storytelling and moral clarity in their entertainment.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Classical Roman history

- Contemporary French literature

- Theatrical melodrama

- Moral tales tradition

- Historical painting

This Film Influenced

- Later Feuillade serials

- French historical dramas of the 1910s

- Moral tales in cinema

- Silent era tragic narratives