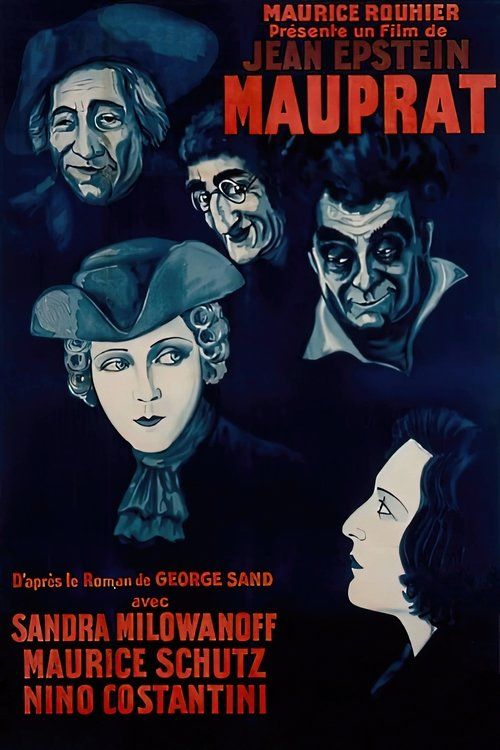

Mauprat

Plot

Orphaned as a child, Bernard de Mauprat is adopted by his uncle Tristan, a brutal brigand who raises him alongside his own sons to become a ruthless killer and thief. Bernard grows into a wild, uncouth young man who knows only violence and plunder, until he encounters his noble relatives Hubert de Mauprat and his beautiful daughter Edmée. Recognizing the goodness buried beneath Bernard's rough exterior, Edmée undertakes the challenge of civilizing him, while Bernard falls deeply in love with her despite her engagement to another man. Through Edmée's patient guidance and Bernard's genuine desire to reform, he gradually transforms from a savage outlaw into a refined gentleman worthy of her love. The film culminates in Bernard's complete redemption as he proves his nobility through selfless acts, ultimately winning Edmée's heart and overcoming his brutal upbringing.

About the Production

Jean Epstein adapted George Sand's 1837 novel with his characteristic avant-garde sensibility, blending literary adaptation with cinematic innovation. The film was produced during Epstein's most creative period, when he was developing his theories of photogénie - the idea that cinema could reveal the essence of reality through the camera lens. The production faced challenges typical of silent era filmmaking, including the need for elaborate period costumes and sets to depict 18th century France.

Historical Background

Mauprat was produced during a golden age of French cinema, just before the transition to sound films would dramatically change the industry. The mid-1920s saw the flourishing of the French avant-garde movement, with filmmakers like Epstein, Abel Gance, and Marcel L'Herbier pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression. This period was also marked by a revival of interest in French literary classics, with many directors adapting works by authors like Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and George Sand. The film reflects the post-WWI cultural climate in France, where there was both nostalgia for pre-revolutionary France and enthusiasm for modern artistic innovation. Epstein's work, including Mauprat, contributed to establishing cinema as a serious art form capable of literary adaptation while maintaining its unique visual language.

Why This Film Matters

Mauprat represents an important moment in the history of literary adaptation in cinema, demonstrating how classic novels could be transformed into distinctly cinematic works while preserving their thematic depth. The film is significant for its role in establishing Jean Epstein as a major figure in French cinema, bridging the gap between commercial filmmaking and artistic innovation. Its successful adaptation of a beloved French literary work helped legitimize cinema as a medium capable of handling complex narratives and themes. The film's exploration of redemption, love, and social transformation resonated with 1920s audiences grappling with the aftermath of World War I and rapid social change. Today, Mauprat is studied as an example of how silent cinema could convey sophisticated emotional and psychological development through visual means alone.

Making Of

Jean Epstein approached the adaptation of George Sand's novel with both reverence for the source material and his desire to push cinematic boundaries. The production involved extensive location scouting for appropriate 18th-century settings, though much was filmed on studio sets. Epstein worked closely with his cinematographers to achieve the visual effects he wanted, particularly in scenes showing Bernard's transformation from savage to nobleman. The casting of Sandra Milovanoff as Edmée was considered a coup, as she was at the height of her popularity. Epstein, who was also a film theorist, used the production as an opportunity to experiment with his ideas about rhythm, movement, and the emotional power of images. The film's editing reflects Epstein's interest in creating emotional impact through rapid cuts and expressive camera movements, techniques that were innovative for the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Mauprat showcases Epstein's innovative approach to visual storytelling, employing techniques that were ahead of their time. The film makes extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting to emphasize the contrast between Bernard's savage past and his emerging nobility. Epstein and his cinematographers employed expressive camera movements, including tracking shots and dramatic angles, to convey emotional states and psychological transformation. The visual style evolves throughout the film, mirroring Bernard's journey from darkness to light - early scenes are shot with darker, more claustrophobic compositions, while later scenes open up to brighter, more expansive framing. The film also makes effective use of close-ups to capture the emotional nuances of the performances, particularly in scenes between Bernard and Edmée. Period detail is rendered with careful attention to lighting and composition, creating a convincing 18th-century atmosphere while maintaining the film's modernist sensibility.

Innovations

Mauprat demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its use of camera movement and editing techniques. Epstein employed sophisticated tracking shots and dynamic camera angles that were unusual for mid-1920s cinema, using the camera not just to record action but to actively participate in storytelling. The film's editing shows advanced understanding of rhythmic cutting, using rapid sequences to convey emotional states and psychological transformation. The production also achieved notable success in creating convincing period atmosphere through detailed set design and costume work, overcoming the technical limitations of studio filmmaking in the 1920s. The film's lighting techniques, particularly its use of shadow and contrast to represent moral and psychological states, were technically sophisticated for the period and influenced subsequent French cinema.

Music

As a silent film, Mauprat would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have consisted of a small orchestra or pianist performing a compiled score that mixed classical pieces with original compositions. The music would have been carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, emphasizing emotional moments and dramatic transitions. For the film's romantic scenes, popular classical pieces by composers like Chopin or Debussy might have been used, while more dramatic or action sequences would have required more intense musical accompaniment. Modern screenings of restored versions often feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture both the period setting and the film's avant-garde sensibility, using a combination of period-appropriate instruments and contemporary musical techniques.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'Can a man born to violence learn to love?' 'Her faith in him became his salvation' 'From the darkness of his past, a new man emerged' 'Love conquered the beast within' 'Nobility is not born, it is earned through deeds'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic opening sequence showing Bernard's brutal upbringing among the brigands, establishing his savage nature through stark visual contrasts and aggressive camera work

- The first encounter between Bernard and Edmée, where her beauty and kindness immediately begin to transform him, captured through soft focus lighting and gentle camera movement

- The pivotal scene where Bernard chooses to defend Edmée's honor rather than continue his life of crime, marking his moral turning point

- The climactic duel sequence where Bernard proves his transformation through noble conduct, filmed with dynamic action and emotional intensity

- The final reconciliation scene between Bernard and Edmée, where their love triumphs over social barriers, captured through romantic lighting and intimate close-ups

Did You Know?

- Jean Epstein was only 28 years old when he directed this ambitious literary adaptation

- The film is based on George Sand's 1837 novel of the same name, one of her most popular works

- Sandra Milovanoff, who plays Edmée, was one of the most popular French actresses of the 1920s

- The film showcases Epstein's theory of 'photogénie' - his belief that cinema could reveal the essential nature of reality

- Mauprat was considered one of Epstein's most successful commercial films during his lifetime

- The film's restoration in recent years has brought new attention to Epstein's contribution to French cinema

- George Sand's novel was controversial in its time for its feminist themes and critique of social conventions

- The film was released during the height of the French avant-garde movement, alongside works by filmmakers like Luis Buñuel and Jean Renoir

- Epstein's adaptation was praised for preserving the romantic spirit of Sand's novel while adding cinematic innovation

- The film's period detail and costumes were particularly noted by contemporary critics for their authenticity

What Critics Said

Contemporary French critics praised Mauprat for its successful blend of literary adaptation and cinematic innovation, with particular appreciation for Epstein's visual style and the performances of the leads. Critics noted how Epstein managed to capture the romantic spirit of George Sand's novel while adding his own cinematic poetry. The film was recognized as one of Epstein's more accessible works, balancing his avant-garde tendencies with narrative clarity. Modern critics and film scholars have reevaluated Mauprat as an important example of 1920s French cinema, highlighting its role in the development of film language and its sophisticated approach to literary adaptation. Recent restorations have allowed new generations of critics to appreciate the film's visual beauty and emotional power, with many noting its influence on subsequent period films and romantic dramas.

What Audiences Thought

Mauprat was well-received by French audiences upon its release in 1926, proving to be one of Epstein's more commercially successful films. The romantic story and dramatic transformation of the protagonist resonated with moviegoers of the era, who appreciated both the literary pedigree and the visual spectacle. The film's themes of redemption and the power of love to transform human nature had broad appeal across different social classes. Sandra Milovanoff's performance as Edmée was particularly popular with audiences, cementing her status as one of France's leading actresses. While the film did not achieve the blockbuster status of some contemporary productions, it maintained a steady run in French theaters and was subsequently exported to other European countries, where it found appreciative audiences among art film enthusiasts.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented for 1926 French films

Film Connections

Influenced By

- George Sand's 1837 novel 'Mauprat'

- French Romantic literary tradition

- 19th century French realist literature

- German Expressionist cinema (visual style)

- Soviet montage theory (editing techniques)

- French literary adaptation tradition

- Silent era melodrama conventions

- Avant-garde film movements of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent French literary adaptations

- Period romantic dramas

- Films about redemption and transformation

- French poetic realist films of the 1930s

- Later Jean Epstein works

- French heritage films of later decades

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Mauprat has survived the decades in varying degrees of completeness. While not considered a lost film, some versions may be incomplete or damaged. The film has undergone restoration efforts by film archives, particularly French institutions dedicated to preserving cinematic heritage. Recent digital restorations have made the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical significance. The restoration work has revealed the sophistication of Epstein's visual style and the film's technical achievements. Some original elements may still be missing or degraded, but enough material exists to present a coherent version of the film.