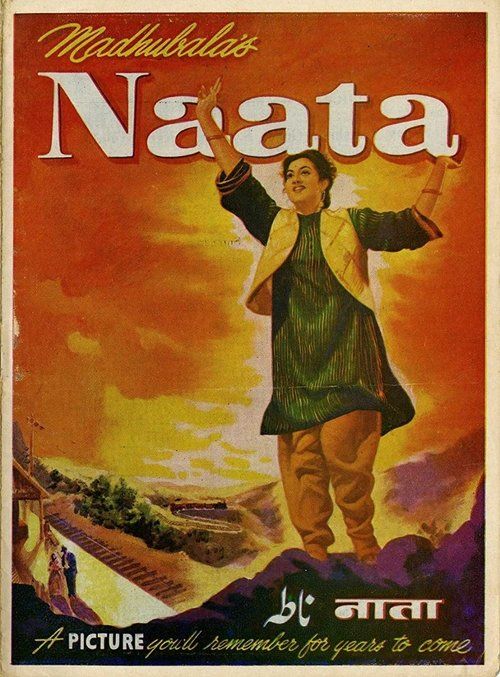

Naata

Plot

Naata tells the poignant story of a young woman who narrates the complex relationship between her sister and a postmaster in rural India. The film explores themes of love, social barriers, and the challenges faced by women in traditional society. As the story unfolds through the narrator's perspective, viewers witness the emotional journey of the sister-postmaster relationship, which faces obstacles from family expectations and societal norms. The narrative delicately portrays how communication through letters becomes both a bridge and a barrier for the lovers. The film culminates in a powerful exploration of whether true love can transcend the rigid social structures of 1950s India.

About the Production

Naata was produced during the golden era of Indian cinema when parallel cinema was gaining prominence. The film was shot in black and white using the technology available in mid-1950s India. Director D.N. Madhok, known for his socially conscious themes, took particular care in casting Madhubala against type, moving away from her usual glamorous roles. The production faced challenges typical of the era, including limited studio facilities and the need to shoot on actual locations for authentic rural settings.

Historical Background

Naata was produced in 1955, during a pivotal period in Indian cinema when the country was establishing its post-independence cultural identity. The film emerged during the early years of the Indian Parallel Cinema movement, which sought to create more realistic and socially relevant content distinct from mainstream commercial films. This era saw the rise of filmmakers who were influenced by Italian neorealism and wanted to address contemporary social issues through cinema. The 1950s also marked a significant transformation in Indian society, with questions about tradition versus modernity, women's roles, and social reform being widely debated. Naata's focus on rural India and the postal system reflected the importance of communication in a newly independent nation trying to connect its diverse regions. The film's release came just a few years after India adopted its constitution and was grappling with questions of social equality and reform.

Why This Film Matters

Naata holds an important place in Indian cinema history as one of the early films that attempted to bridge the gap between commercial and parallel cinema. The film's exploration of women's perspectives through its narrative structure was progressive for its time, offering a female narrator's viewpoint on relationships and social constraints. It contributed to the ongoing discourse about women's agency in traditional Indian society, particularly in rural settings. The film's realistic portrayal of rural life and the postal system provided valuable documentation of mid-20th century Indian social structures. Madhubala's participation in such a socially conscious film helped legitimize the parallel cinema movement and encouraged other mainstream actors to take on serious roles. The film's thematic focus on communication barriers and social hierarchies resonated with audiences dealing with rapid social change in post-independence India.

Making Of

The making of Naata represented a significant shift in Madhubala's career trajectory, as she consciously chose this role to demonstrate her range beyond commercial cinema. Director D.N. Madhok spent months researching rural post office operations to ensure authenticity in the film's depiction. The production team faced considerable challenges securing filming permits for actual post office locations, as government facilities were rarely made available for film shoots during that era. The chemistry between Abhi Bhattacharya and Vijayalakshmi was reportedly developed through extensive rehearsal sessions, as Madhok believed in method acting techniques. The film's cinematographer experimented with natural lighting techniques for outdoor sequences, which was innovative for Indian cinema of the 1950s. Several scenes had to be reshot due to technical issues with the sound recording equipment, a common problem in Indian studios of that period.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Naata was handled by V. Avadhani, who employed a realistic visual style that distinguished it from the more theatrical cinematography typical of mainstream Indian cinema of the 1950s. The film made extensive use of natural lighting, particularly in outdoor sequences depicting rural life, which was innovative for its time. The camera work emphasized close-ups to capture subtle emotional expressions, especially in scenes involving the sister-postmaster relationship. The cinematographer used deep focus techniques to maintain authenticity in the post office scenes, allowing viewers to observe the detailed workings of rural postal services. The black and white photography utilized strong contrasts to highlight the social divisions and emotional tensions central to the story. The visual composition often framed characters through doorways and windows, symbolizing the barriers and constraints they faced in society.

Innovations

Naata demonstrated several technical achievements for Indian cinema of its time. The film pioneered the use of on-location sound recording for outdoor scenes, which was challenging given the limited portable recording equipment available in the 1950s. The production team developed innovative techniques for filming in actual post office environments without disrupting daily operations. The film's editing employed jump cuts and cross-cutting techniques that were relatively advanced for Indian cinema of that period, particularly in sequences showing parallel emotional journeys. The sound design incorporated authentic ambient sounds of rural India, from post office operations to village life, creating a more immersive experience. The film also experimented with narrative structure through its use of a frame story, which was uncommon in Indian cinema of the 1950s.

Music

The music for Naata was composed by S.N. Tripathi, with lyrics penned by the director D.N. Madhok himself, leveraging his background as a lyricist. The soundtrack featured eight songs that blended classical Indian ragas with folk elements, reflecting the rural setting of the film. Notable singers of the era including Lata Mangeshkar, Manna Dey, and Asha Bhosle lent their voices to the songs. The music was intentionally kept subtle and background-oriented to maintain the film's realistic tone, avoiding the elaborate musical sequences typical of commercial Bollywood films. The soundtrack included several melancholic melodies that underscored the emotional journey of the characters. One particular song about letters and waiting became popular for its poetic representation of long-distance relationships in the pre-telephone era. The film's score used minimal orchestration, relying primarily on traditional Indian instruments to enhance the rural atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

Letters carry more than words; they carry the weight of hearts separated by distance and society

In a world where voices are silenced, written words become the only truth

Sometimes the greatest distance between two people is not measured in miles, but in social barriers

A postmaster delivers not just letters, but dreams, hopes, and sometimes, heartbreak

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the narrator begins telling her sister's story while sitting under a banyan tree

- The tense confrontation scene where family members discover the relationship between the sister and postmaster

- The poignant sequence of letters being sorted and delivered, intercut with the emotional reactions of recipients

- The climactic scene where the sister must choose between family duty and personal happiness

- The final montage showing the passage of time through seasonal changes in the rural landscape

Did You Know?

- Madhubala accepted this role to break away from her typecast glamorous image and prove her acting versatility in serious cinema

- Director D.N. Madhok was also a prolific lyricist and wrote several songs for films before becoming a director

- The film's title 'Naata' translates to 'relationship' or 'kinship' in Hindi, reflecting its central theme

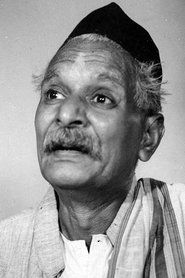

- Abhi Bhattacharya was known for his work in parallel cinema and was particularly chosen for his natural acting style

- The post office scenes were filmed in an actual working post office in rural Maharashtra to maintain authenticity

- The film was one of the early Indian productions to explore the narrative device of having a story told through a third-party narrator

- Vijayalakshmi, who played the sister role, was a prominent character actress in Bengali cinema making her mark in Hindi films

- The film's release coincided with the early stages of the Indian Parallel Cinema movement

- Original prints of the film used silver nitrate stock, which was common but highly flammable during that period

- The screenplay was adapted from a short story by a regional Indian writer, though the original author's name is lost in records

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Naata was generally positive, with reviewers particularly praising Madhubala's performance and the film's social relevance. Critics noted the film's departure from conventional Bollywood tropes and its attempt at realistic storytelling. The Times of India review highlighted the film's "courageous narrative structure" and "authentic rural portrayal." Filmfare magazine commended director D.N. Madhok for his sensitive handling of the subject matter. However, some critics felt the pacing was slow compared to commercial cinema of the time. Modern film historians have reassessed Naata as an important transitional work in Indian cinema, noting its role in the development of parallel cinema. The film is now recognized for its ahead-of-its-time feminist perspective and its contribution to Indian cinema's social consciousness.

What Audiences Thought

Naata received a mixed response from audiences upon its release in 1955. While urban audiences and educated viewers appreciated the film's serious themes and realistic approach, mainstream moviegoers found it slower and less entertaining than typical Bollywood fare of the era. The film performed moderately well in metropolitan cities like Bombay and Calcutta but struggled in smaller towns where audiences preferred more commercial entertainment. Madhubala's fan base was initially divided, with some disappointed by her departure from glamorous roles, while others praised her versatility. Over time, the film gained cult status among cinema enthusiasts and students of Indian film history. In retrospectives, audiences have come to appreciate the film's artistic merits and its historical significance in Indian cinema's evolution.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism movement

- Early Indian parallel cinema

- Satyajit Ray's early works

- Social realist literature of India

- Traditional Indian folk storytelling

- Bengali literary traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later parallel cinema works exploring rural themes

- Films featuring female narrators in Indian cinema

- Socially conscious Bollywood films of the 1960s

- Regional cinema dealing with similar themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Naata is concerning, as is common with many Indian films from the 1950s. Original nitrate prints are believed to have deteriorated over time, and the National Film Archive of India does not list a complete preserved copy in their collection. Some fragmented prints and partial reels exist in private collections and regional archives, but a complete, restored version is not currently available to the public. The film's survival is threatened by the natural decay of nitrate film stock and the lack of systematic preservation efforts during the mid-20th century in India. Film preservationists have attempted to locate surviving elements for potential restoration, but the process has been challenging due to the scattered nature of existing prints.