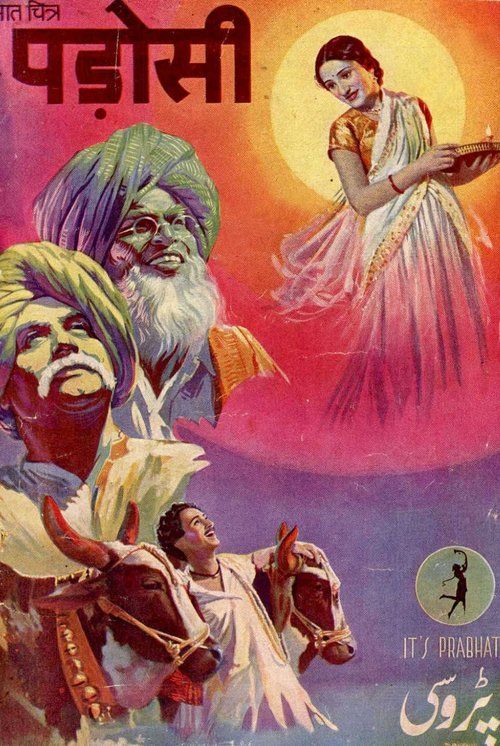

Padosi

"Unity in Diversity - A Timeless Message of Harmony"

Plot

Set in a small Indian village, 'Padosi' portrays the harmonious coexistence of Hindu and Muslim communities who live as neighbors sharing daily life, celebrations, and struggles. The peaceful equilibrium is disrupted when a cunning industrialist arrives with plans to construct a dam, strategically exploiting religious differences to turn the communities against each other for his own benefit. As mistrust grows and old friendships fracture, the film follows the journey of villagers who must overcome the manufactured divisions to restore their unity. The narrative culminates in a powerful realization that their strength lies in unity rather than division, delivering a profound message about communal harmony that remains relevant decades later.

About the Production

This was a bilingual production made simultaneously in Hindi ('Padosi') and Marathi ('Shejari'). V. Shantaram used this technique to reach broader audiences across linguistic boundaries. The film was shot during a sensitive period of rising communal tensions in pre-independence India, making its message particularly bold and relevant. The dam construction sequences were innovative for their time, using miniatures and special effects to create realistic industrial imagery.

Historical Background

Produced in 1941 during the height of World War II and just before the Quit India Movement of 1942, 'Padosi' emerged during one of the most tumultuous periods in Indian history. The British colonial government was actively pursuing divide-and-rule policies, exacerbating Hindu-Muslim tensions to maintain control. Communal riots were becoming increasingly common, and the demand for Pakistan was gaining momentum. Against this backdrop, V. Shantaram's decision to make a film celebrating communal harmony was not just artistic but deeply political. The film's message of unity directly challenged the colonial narrative that Indians were incapable of governing themselves due to internal divisions. The dam construction subplot was particularly significant, as it represented the exploitation of Indian resources by foreign interests, a major grievance that fueled the independence movement. The film's release came just months before the Japanese bombing of Calcutta and Madras, events that would further complicate India's political landscape.

Why This Film Matters

'Padosi' holds a unique place in Indian cinema history as one of the earliest films to tackle communal harmony as its central theme. Its influence extends beyond cinema into the broader cultural discourse on religious tolerance in India. The film established a template for social messaging in Indian cinema that would be emulated by filmmakers for decades. Its bilingual production approach (Hindi and Marathi versions) demonstrated the potential for cinema to transcend linguistic barriers in India's diverse cultural landscape. The film's songs, particularly those emphasizing unity, became part of the popular consciousness and were sung at community gatherings and even at some political meetings. The character archetypes established in 'Padosi' - the wise elder, the innocent lovers caught in communal strife, the manipulative outsider - became recurring elements in subsequent Indian films dealing with similar themes. The film's preservation and continued discussion in academic circles underscore its enduring relevance to conversations about secularism and national unity in India.

Making Of

The production of 'Padosi' was marked by V. Shantaram's passionate commitment to social cinema. He reportedly spent months researching communal tensions in rural India, visiting villages to understand the dynamics between Hindu and Muslim communities. The casting process was deliberately designed to promote off-screen harmony - Shantaram ensured that actors from different religious backgrounds worked closely together during filming. The dam sequences required innovative techniques, as the production team built elaborate miniatures and used forced perspective photography to create the illusion of massive construction. The film's music was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, who worked closely with Shantaram to create songs that would reinforce the film's message of unity. During filming, there were reportedly tensions with colonial authorities who were suspicious of the film's potential to incite unity against British rule, but Shantaram managed to navigate these challenges by emphasizing the film's focus on internal Indian harmony rather than anti-colonial themes.

Visual Style

The cinematography by V. Avadhoot was pioneering for its time, employing techniques that were innovative in Indian cinema. The film used extensive location shooting in actual villages, which was uncommon in 1941 when most films were shot entirely on studio sets. Avadhoot employed natural lighting for many outdoor scenes, creating a realistic and authentic visual texture. The dam construction sequences featured sophisticated miniature photography and forced perspective techniques to create the illusion of massive industrial projects. The film's visual contrast between the idyllic rural life and the disruptive industrial elements was achieved through careful composition and lighting choices. Avadhoot also experimented with deep focus photography, allowing both foreground and background elements to remain sharp in key scenes, enhancing the sense of community and shared space. The communal harmony scenes were often shot with wide angles to include characters from both communities in the same frame, visually reinforcing the film's central message.

Innovations

'Padosi' showcased several technical innovations for Indian cinema in 1941. The film's bilingual production technique, shooting simultaneously in Hindi and Marathi, was groundbreaking and required meticulous planning and execution. The dam construction sequences featured advanced special effects using miniatures and composite photography, techniques that were rarely used in Indian cinema at the time. The film employed location sound recording for some outdoor scenes, a challenging feat given the limited technology available. The production team developed innovative techniques for creating realistic crowd scenes, using multiple cameras and careful choreography to portray large village gatherings. The film's editing, particularly in scenes showing parallel lives of Hindu and Muslim families, used cross-cutting techniques that were sophisticated for the period. The makeup and costume departments created authentic rural looks that avoided the theatrical styling common in films of that era, contributing to the film's realistic approach.

Music

The music for 'Padosi' was composed by Keshavrao Bhole, with lyrics by Diwan Sharar and Pandit Indra. The soundtrack was notable for its integration of both Hindu and Muslim musical traditions, featuring instruments and melodies from both cultures. Songs like 'Hindu Muslim Ek Hai' (Hindu and Muslim are One) became anthems of communal harmony. The film included both classical and folk musical elements, reflecting the rural setting while maintaining artistic sophistication. The background score used subtle motifs to represent different communities, which would then merge during scenes of harmony. The playback singing featured voices that could authentically represent both musical traditions, with some songs performed in a style that deliberately blended Hindu and Muslim musical elements. The soundtrack was released on gramophone records and became popular even among those who hadn't seen the film, contributing to its social impact.

Famous Quotes

Hum Hindu ya Muslim nahi, hum insaan hain - padosi hain

We are not Hindu or Muslim, we are human - we are neighbors)

Dharati sabki maa hai, uske liye sabko milkar kaam karna hoga

Earth is everyone's mother, we must work together for her)

Jab log ek hote hain, toh koi taqat unhe tod nahi sakti

When people are united, no power can break them)

Bhai-chara ki neev par hi hamara gaon basa hai

Our village is built on the foundation of brotherhood)

Pani ki tarah hum bhi ek hain, ek hi nadi ki dharayein hain

Like water, we are one, currents of the same river)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Hindu and Muslim families sharing water from the same well, establishing the film's theme of harmony

- The emotional confrontation scene where the elderly village leader confronts the industrialist about his divisive tactics

- The dam construction sequence with its innovative special effects showing the disruption of village life

- The climactic scene where villagers from both communities unite to stop the dam construction

- The wedding sequence where Hindu and Muslim traditions are shown being celebrated together

- The final scene where the industrialist is exposed and villagers reaffirm their commitment to unity

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first Indian films to explicitly address communal harmony as its central theme, a bold stance during the British Raj's divide-and-rule policy

- The film was made in two versions simultaneously - Hindi ('Padosi') and Marathi ('Shejari') - with different actors for some roles but the same director and technical team

- V. Shantaram was so committed to the message of communal harmony that he cast actors from different religious backgrounds in key roles

- The dam construction scenes were considered technically advanced for 1941, using innovative miniature photography and special effects

- The film's release coincided with the Quit India Movement, making its message of unity particularly poignant and politically significant

- Mazhar Khan, who played the Muslim protagonist, was one of the few Muslim actors to achieve stardom in Hindu-dominated Bombay cinema of that era

- The film was shot at Prabhat Studios, which was known for its technical innovations and social messaging

- Despite its serious theme, the film included several musical numbers that became popular and were sung by ordinary people on the streets

- The industrialist character was modeled after real British industrialists who were exploiting Indian resources during the colonial period

- This was among the last major films produced by Prabhat Film Company before it split and V. Shantaram formed his own studio

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Padosi' for its courage in addressing communal harmony during a period of rising tensions. The Times of India (Bombay edition) called it 'a brave and necessary film for our times,' while Film India magazine described it as 'V. Shantaram at his most socially conscious.' Critics particularly noted the balanced portrayal of both communities, avoiding stereotypes that were common in cinema of the era. The performances of Mazhar Khan and Gajanan Jagirdar were widely acclaimed for their authenticity and emotional depth. Modern critics and film historians have revisited 'Padosi' as a landmark film, with the National Film Archive of India describing it as 'ahead of its time in its treatment of communal harmony.' The film's technical aspects, especially the dam construction sequences, were noted as innovative by contemporary trade publications. Some critics did note that the film's message was somewhat idealistic, but most agreed that this idealism was necessary given the historical context.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1941 received 'Padosi' with enthusiasm, particularly in urban centers like Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras where communal tensions were most palpable. The film reportedly ran for several weeks in major theaters, an achievement for that era. Muslim and Hindu audiences were said to attend screenings together, with some reports of spontaneous applause during scenes of inter-community friendship. The film's songs became popular on the streets and were sung by people from both communities. In rural areas, where the film reached through traveling theaters, audiences connected strongly with the village setting and relatable characters. However, some conservative elements from both communities reportedly objected to the film's message of inter-religious harmony, viewing it as unrealistic or politically motivated. Despite this, the film's overall reception was positive, with many viewers writing letters to newspapers expressing how the film had changed their perspective on communal issues.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film at the Bombay Film Society Awards (1941)

- Best Director - V. Shantaram at the Indian Motion Picture Congress (1942)

- Best Social Film recognition from the Film Journalists Association (1942)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian socialist cinema of the 1930s

- Indian traditional folk theater

- British documentary filmmaking tradition

- Previous V. Shantaram social films like 'Duniya Na Mane'

- Indian independence movement literature

- Gandhian philosophy of communal harmony

This Film Influenced

- Garam Hawa (1973)

- M.S. Dhoni: The Untold Story (2016)

- Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015)

- PK (2014)

- Lagaan (2001)

- Mother India (1957)

- Garam Hawa (1973)

- Bombay (1995)

- Pinjar (2003)

- Kashmir (1975)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The National Film Archive of India has preserved both Hindi ('Padosi') and Marathi ('Shejari') versions of the film. While complete prints exist, some deterioration is evident due to the age of the nitrate stock. The Film Heritage Foundation undertook restoration work in 2015, digitally preserving the film and improving visual quality. Some scenes, particularly from the dam construction sequence, show signs of wear but remain viewable. The soundtrack has been fully preserved and remastered. The film is occasionally screened at classic film festivals and retrospectives, particularly those focusing on V. Shantaram's work or early Indian cinema. Both versions are considered important cultural heritage and are protected under India's National Film Heritage Mission.