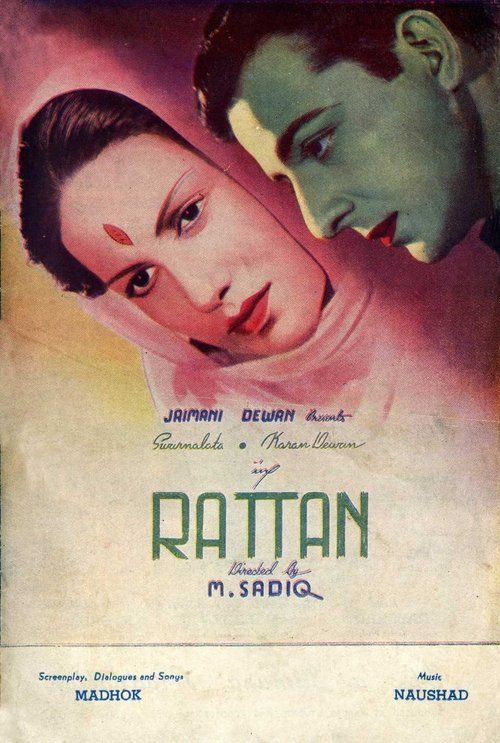

Ratan

Plot

Ratan tells the poignant story of childhood sweethearts Ratan and Mohan who have grown up together in a small village, sharing dreams of a future together. Their innocent romance is shattered when circumstances force Ratan to marry an older, wealthy widower who has a young child from his previous marriage. On their wedding night, the husband sees Ratan's youthful face for the first time and is overcome with guilt, believing he has robbed her of her youth and happiness, leading him to maintain a platonic relationship. Years pass in this emotionally barren marriage until Ratan returns to her village to visit her ailing mother, where she encounters Mohan again, reigniting their suppressed feelings and forcing Ratan to confront the choices that have defined her life.

About the Production

Ratan was produced during the peak of the Bombay Talkies era, when Indian cinema was transitioning from silent films to talkies. The film was shot on black and white celluloid using the technology available in the 1940s, with sound recording done on magnetic tape. The production faced challenges due to World War II, which affected film stock availability and caused delays in scheduling.

Historical Background

Ratan was produced and released during a tumultuous period in Indian history. The year 1944 saw India deeply involved in World War II, with the British Raj still in control but facing increasing pressure from the independence movement. The film industry, particularly in Bombay, was experiencing a golden age despite wartime constraints. Cinema had become one of the most powerful mediums for social commentary and cultural expression. The film's themes of women's autonomy and the questioning of traditional marriage arrangements reflected the broader social reforms being discussed in Indian society. This period also saw the emergence of a distinctly Indian cinematic language, moving away from theatrical influences toward more realistic storytelling. The film's release came at a time when Indian audiences were increasingly looking for content that reflected their social realities and aspirations for a free India.

Why This Film Matters

Ratan holds significant cultural importance as one of the early Indian films to address women's issues and the institution of marriage from a feminist perspective. The film contributed to the discourse on women's rights and agency in a society where arranged marriages and age disparities were common. Its portrayal of a woman's emotional life and desires was groundbreaking for its time. The film's music became part of the cultural lexicon, with several songs becoming evergreen classics that are still remembered and referenced today. Ratan influenced a generation of filmmakers to tackle socially relevant subjects and demonstrated that commercial cinema could successfully address serious social issues. The film's success paved the way for more women-centric narratives in Indian cinema and helped establish the template for the social drama genre that would flourish in post-independence Indian cinema.

Making Of

The making of Ratan was marked by several interesting anecdotes and challenges. Director M. Sadiq was known for his meticulous attention to detail and would often spend hours rehearsing emotional scenes with his actors. Swaran Lata reportedly prepared for her role by spending time with women in similar situations to understand their emotional state. The film's music composer, Gyan Dutt, worked closely with the lyricist to create songs that would enhance the narrative rather than merely entertain. During production, the film faced censorship challenges due to its bold subject matter, but the filmmakers successfully argued that the film was addressing a real social problem. The famous scene where Ratan returns to her village took three days to shoot as Sadiq wanted to capture the perfect emotional transition in Swaran Lata's performance.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Ratan was handled by B. Damle, who employed the visual language of the 1940s Bombay cinema while adding subtle innovations. The film used dramatic lighting to emphasize the emotional states of the characters, particularly in scenes depicting Ratan's isolation in her marriage. The village sequences were shot with natural lighting to create a warm, nostalgic atmosphere that contrasted with the cold, formal lighting of Ratan's marital home. Camera movements were deliberately restrained, reflecting the theatrical influence that was still prevalent in Indian cinema of the era. The film made effective use of close-ups to capture the subtle emotional performances of the actors, particularly Swaran Lata. The black and white photography enhanced the film's emotional gravity, with high contrast lighting used to symbolize the moral and emotional conflicts in the narrative.

Innovations

Ratan employed several technical innovations that were noteworthy for its time. The film utilized advanced sound recording techniques for the era, achieving clearer dialogue reproduction than many contemporaneous productions. The editing employed sophisticated cross-cutting techniques to build emotional tension, particularly in the sequences showing parallel lives of the separated lovers. The film's makeup and prosthetics for the older husband character were considered advanced for 1940s Indian cinema. The production design successfully created distinct visual worlds for the village and urban settings, enhancing the narrative's emotional contrast. The film also experimented with narrative structure, using flashbacks more extensively than was typical for the period. These technical achievements, while subtle by modern standards, contributed to the film's effectiveness and demonstrated the growing sophistication of Indian film craft in the 1940s.

Music

The music of Ratan was composed by Gyan Dutt, with lyrics penned by Pandit Indra Chandra. The soundtrack became one of the most celebrated aspects of the film, with several songs achieving iconic status. The music blended classical Indian ragas with the emerging Bombay film music style, creating melodies that were both sophisticated and accessible. Notable songs included 'Aaj Ki Raat Badi Shokh Hai,' 'Dukh Ke Din Ab Beetat Nahin,' and 'Jhoome Jhoome Bachpan Ki Yaaden,' each perfectly complementing the film's emotional narrative. The playback singing was handled by some of the era's most respected vocalists, including Zohrabai Ambalewali and Amirbai Karnataki. The music was recorded using the mono technology available in the 1940s, but the arrangements were rich and layered, incorporating traditional Indian instruments with Western orchestral elements. The soundtrack's popularity contributed significantly to the film's commercial success and cultural impact.

Famous Quotes

"Zindagi ki raahon mein hum akele the, akele hain, aur akele rahenge" - Ratan's reflection on her isolation

"Bachpan ki yaaden kyun satati hain jab waqt guzar gaya ho?" - Mohan questioning nostalgia

"Shadi ek bandhan hai, par bandhan se pehle insaan hai" - The older husband's moral realization

"Mohabbat ki umar kya hoti hai? Jab dil chaahe, tab waqt ho jaata hai" - Dialogue on love and timing

"Ghar woh nahi jahaan rehte hain, ghar woh jahaan dil rehta hai" - Ratan on finding emotional home

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional wedding night scene where the husband sees Ratan's face and is overcome with guilt, shot with minimal dialogue and maximum emotional impact through lighting and performance

- The village reunion scene where Ratan and Mohan meet after years, capturing the awkwardness of their changed circumstances and lingering feelings

- The final confrontation scene where Ratan must choose between her duty and her heart, filmed in long takes to emphasize the weight of her decision

- The childhood flashback sequence showing young Ratan and Mohan's innocent friendship, shot with warm lighting and soft focus to create nostalgia

- The scene where Ratan sings to her stepchild, establishing her maternal nature despite her own emotional emptiness

Did You Know?

- Ratan was one of the early films to address the sensitive topic of age disparity in marriages, which was a common social issue in 1940s India

- The film's music became extremely popular, with several songs becoming chart-toppers and remaining popular for decades

- Swaran Lata, who played the lead role, was one of the highest-paid actresses of the 1940s and was known for choosing socially relevant roles

- Director M. Sadiq was known for his social consciousness and often made films that addressed women's issues and social reform

- The film was released during the final years of British rule in India, just three years before independence

- Karan Dewan and Swaran Lata starred together in multiple films and were considered one of the popular on-screen pairs of the 1940s

- The child actor in the film went on to have a successful career as a character actor in later decades

- Ratan's success led to several remakes in different Indian languages over the decades

- The film's original negatives were believed lost for decades before being discovered in the National Film Archive of India

- The costume design for Swaran Lata's character became influential in 1940s Indian fashion

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Ratan for its bold subject matter and sensitive handling of complex social issues. Film India magazine, one of the most influential film publications of the era, described it as 'a courageous attempt to bring women's issues to the forefront of popular cinema.' Critics particularly praised Swaran Lata's performance, noting her ability to convey complex emotions with subtlety and depth. The direction by M. Sadiq was commended for its mature approach to the subject matter. Modern film historians have revisited Ratan as an important early example of feminist cinema in India, with scholars noting its progressive stance on women's autonomy and its critique of patriarchal marriage practices. The film is often cited in academic discussions about the evolution of social consciousness in Indian cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Ratan was a commercial success upon its release, resonating strongly with audiences across India. The film's emotional core and relatable characters struck a chord with viewers, particularly women who saw their own struggles reflected in Ratan's journey. The music became extremely popular, with songs from the film being played on radio stations across the country for months after the release. Audience letters to film magazines of the era reveal that many viewers appreciated the film's courage in addressing a taboo subject. The film's success at the box office demonstrated that audiences were ready for more mature, socially relevant content. Word-of-mouth recommendations helped sustain the film's theatrical run for several weeks in major cities. The emotional climax of the film reportedly moved audiences to tears in many theaters, with some reports of standing ovations after screenings.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Influenced by the social reform movements of 1930s-40s India

- Drew inspiration from Bengali literary traditions of social commentary

- Influenced by earlier Bombay Talkies productions addressing social issues

- Inspired by the progressive women's movement in pre-independence India

This Film Influenced

- Several remakes in different Indian languages in the 1950s and 1960s

- Influenced the wave of social dramas in post-independence Indian cinema

- Inspired later films addressing women's issues in marriage

- Influenced the parallel cinema movement of the 1970s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Ratan was considered lost for several decades before original prints were discovered in the National Film Archive of India in the 1980s. The film has undergone partial restoration, though some sequences show signs of deterioration. The National Film Archive of India maintains a preserved copy, though it is not regularly screened. Some private collectors reportedly hold 16mm copies of varying quality. The soundtrack has been better preserved than the visual elements, with several songs surviving in good audio quality. The film remains at risk due to the degradation of nitrate film stock from the 1940s.