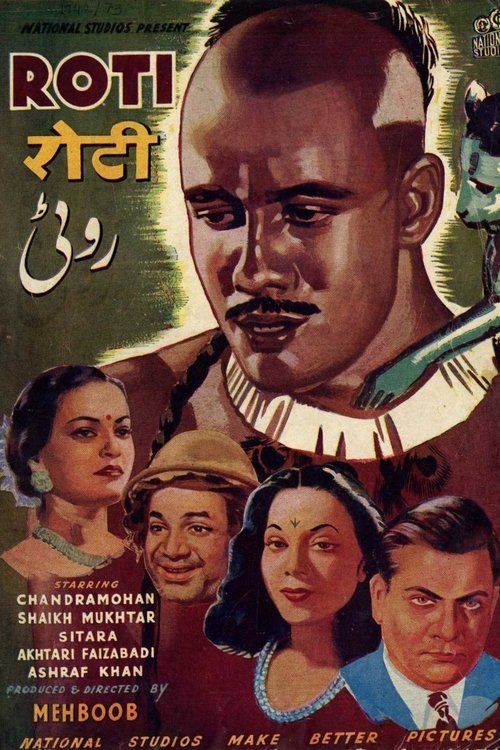

Roti

"A powerful critique of modern civilization versus primitive innocence"

Plot

Roti tells the story of Lalaji, a wealthy industrialist who lives a life of luxury and excess in the city. After his plane crashes in a remote jungle, he is rescued by a tribal couple named Mangal and Meena who live in harmony with nature. Grateful for their help, Lalaji invites them to the city, but the couple finds urban civilization corrupting and soulless. They eventually return to their simple forest life, while Lalaji, facing financial ruin and spiritual emptiness, desperately seeks meaning by returning to the tribal community, only to realize he cannot reclaim the natural purity he once witnessed.

Director

About the Production

The film was made during the Quit India Movement of 1942, adding to its social significance. Mehboob Khan built elaborate jungle sets in the studio to create the contrast between urban and natural environments. The film's production was challenging due to wartime restrictions on film stock and resources.

Historical Background

Roti was produced during a critical period in Indian history - 1942, the year of the Quit India Movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi. The film emerged during World War II when India was under British colonial rule and facing significant political and social upheaval. The early 1940s saw growing industrialization in Indian cities, creating a stark contrast with rural and tribal communities. This period also witnessed the rise of Indian parallel cinema that addressed social issues, moving away from purely entertainment-focused films. The film's critique of materialism and industrialization resonated deeply with the freedom movement's emphasis on returning to Indian roots and values. Mehboob Khan, like many artists of his time, used cinema as a medium to comment on social issues while working within the constraints of colonial censorship.

Why This Film Matters

Roti stands as a landmark in Indian cinema history for its bold social commentary and artistic innovation. It was among the first Indian films to use cinema as a medium for serious social critique, particularly regarding the dangers of unchecked industrialization and materialism. The film's influence can be seen in later Indian parallel cinema movements of the 1950s-70s. Its visual style, incorporating German Expressionist techniques, expanded the artistic vocabulary of Indian filmmaking. The film's themes about the conflict between traditional values and modernization remain relevant in contemporary India. Roti established Mehboob Khan as a director willing to tackle complex social issues, paving the way for his later masterpiece 'Mother India'. The film is often cited by film scholars as an early example of Indian cinema's potential for social commentary and artistic expression.

Making Of

Mehboob Khan was deeply influenced by European cinema, particularly German Expressionist films like 'Nosferatu' and 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari'. He studied these films extensively and incorporated their dramatic lighting, angular sets, and psychological intensity into Roti. The production faced numerous challenges during World War II, including shortages of film stock and equipment. Khan insisted on building elaborate sets to create the contrast between the urban jungle and the natural forest. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with Chandramohan spending time studying wealthy industrialists to understand their psychology, while Sheikh Mukhtar and Sitara Devi researched tribal communities to bring authenticity to their roles. The film's social message was so strong that it underwent several rounds with British censors before approval.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Roti was revolutionary for its time, heavily influenced by German Expressionism. Cinematographer Faredoon Irani used dramatic lighting techniques with strong contrasts between light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create psychological tension. The urban sequences were shot with angular compositions and distorted perspectives to convey the corruption and artificiality of city life. In contrast, the jungle scenes used softer, more natural lighting to represent purity and harmony. The film employed innovative camera movements and angles that were uncommon in Indian cinema of the 1940s. Special attention was given to visual metaphors, such as using shadows to represent the characters' inner conflicts. The film's visual style created a powerful dichotomy between the mechanical world of the city and the organic world of the forest.

Innovations

Roti achieved several technical milestones for Indian cinema in 1942. The film pioneered the use of German Expressionist lighting techniques in Indian films, creating dramatic shadows and contrasts. The production design featured innovative set constructions that could transform from urban to jungle environments. Special effects techniques, including matte paintings and miniatures, were used to create the illusion of vast jungle landscapes within studio constraints. The film's sound design was advanced for its time, using natural sounds from the jungle environment to create atmospheric contrast with urban noise. The editing employed rapid cuts in urban sequences to convey chaos and longer, flowing takes in natural settings to represent harmony. These technical innovations helped establish new possibilities for visual storytelling in Indian cinema.

Music

The music for Roti was composed by Anil Biswas, one of the most respected music directors of the era. The soundtrack featured songs that contrasted the artificial urban music with natural, folk-inspired melodies for the tribal sequences. The film's songs were not just entertainment but served to reinforce the central themes. Notable songs included 'Dukh Ke Din Ab Beetat Nahin' which expressed the emptiness of material wealth, and 'Jungle Mein Mangal Shobha' which celebrated natural living. The background score used orchestral arrangements for city scenes and simpler, folk instruments for forest sequences. The soundtrack was praised for its ability to enhance the film's social message while remaining accessible to audiences.

Famous Quotes

Roti sirf pet nahi bharati, dil aur dimag bhi nark mein le jaati hai

Bread doesn't just fill the stomach, it takes the heart and mind to hell),

Jab insaan paisa ke peeche bhagta hai, woh insaan se shernasheer ho jaata hai

When a man runs after money, he becomes worse than an animal),

Shahar ki roshni mein andhera chhupa hai, jungle ki andheri mein roshni

In the city's light, darkness is hidden; in the jungle's darkness, there is light)

Hamari sanskriti hamari pehchan hai, machine hamari barbaadi

Our culture is our identity, machines are our destruction)

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic airplane crash sequence using innovative special effects and camera techniques

- The first meeting between Lalaji and the tribal couple, highlighting the stark contrast between their worlds

- The transformation of the tribal characters as they experience city life for the first time

- Lalaji's breakdown in his empty mansion, surrounded by wealth but devoid of happiness

- The final scene where Lalaji returns to the forest seeking redemption, only to find he cannot belong

- The dance sequence performed by Sitara Devi representing the purity of tribal life

- The montage contrasting the mechanical rhythm of the city with the natural rhythms of the forest

Did You Know?

- Roti was one of the first Indian films to be heavily influenced by German Expressionism, particularly in its visual style and lighting techniques

- Director Mehboob Khan considered this one of his most socially relevant works, even more so than his later masterpiece 'Mother India'

- The film's critique of industrialization and capitalism was unusually bold for its time, especially during British colonial rule

- Chandramohan's performance as the millionaire Lalaji was considered groundbreaking for its psychological depth

- The tribal characters were played by Sheikh Mukhtar and Sitara Devi, who underwent extensive preparation to understand tribal lifestyles

- The film's title 'Roti' (bread) symbolizes both basic human needs and the corruption that comes from material excess

- Despite its artistic merits, the film faced censorship challenges due to its social critique

- The jungle sequences were filmed using innovative techniques with miniature models and matte paintings

- The film's message about the dangers of unchecked industrialization was prophetic for post-independence India

- Sitara Devi, known primarily as a dancer, delivered a highly praised dramatic performance in this film

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Roti for its bold themes and artistic ambitions. The Times of India called it 'a courageous attempt to use cinema as a mirror to society' while Film India magazine described it as 'a milestone in Indian filmmaking'. Critics particularly noted the film's visual style and Chandramohan's performance. Modern film scholars have re-evaluated Roti as an important precursor to the Indian New Wave cinema of the 1950s-60s. The film is now studied in film schools for its early use of Expressionist techniques in Indian cinema and its sophisticated social commentary. Critics today appreciate how Mehboob Khan managed to deliver a powerful social critique within the commercial cinema framework of the 1940s.

What Audiences Thought

Upon its release in 1942, Roti received a mixed response from audiences. While educated urban viewers appreciated its social message and artistic qualities, mass audiences found it too serious and preachy compared to typical commercial films of the era. The film's runtime of nearly three hours was also challenging for audiences accustomed to shorter entertainments. However, the film developed a cult following among intellectuals and film enthusiasts. Over time, as Indian audiences became more sophisticated, Roti gained appreciation as a pioneering work. Today, film enthusiasts and students of cinema regard it as a classic that was ahead of its time. The film's themes about materialism versus simplicity have found renewed relevance in contemporary India.

Awards & Recognition

- No major formal awards were given for Indian films in 1942, but received critical acclaim at film screenings

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari' and 'Nosferatu')

- Charlie Chaplin's 'Modern Times' for its critique of industrialization

- Russian cinema of the 1920s for its social messaging

- Indian traditional folk tales about simple living

- Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of simple living and rural development

This Film Influenced

- Mehboob Khan's later 'Mother India' (1957) for its social themes

- Satyajit Ray's 'Pather Panchali' (1955) for rural-urban contrast

- Mrinal Sen's 'Bhuvan Shome' (1969) for social critique

- Parallel cinema movement of the 1950s-70s

- Contemporary films addressing environmental and social issues

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Roti is considered partially preserved. Some reels of the film exist in the National Film Archive of India, but the complete version in pristine condition is not available. Parts of the film have been restored, but it remains challenging to view the complete work as originally intended. The film's historical significance has led to ongoing preservation efforts, but like many films from the 1940s, it suffers from nitrate deterioration and incomplete records. Several film institutions worldwide hold fragments of the film, and there have been attempts to reconstruct the most complete version possible from available sources.